en

names in breadcrumbs

Equus grevyi may sometimes compete with domesticated cattle for resources on grazing lands.

The stripes of Grevy's zebras may act as camouflauge, especially at night. Zebras are often hard to spot from large distances at night. The stripes also help to break up the outline of the animal to predators and may help to camouflage them in tall grass. When in the same territory, Grevy's zebras band together in temporary social groups to provide protection from predators.

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: cryptic

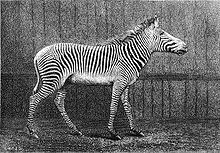

Grevy's zebras have large heads, large and rounded ears, and thick, erect manes. The muzzle is brown. The neck is thicker and more robust than in other zebra species. These qualities make it appear more mule-like than other zebras. The coat has black and white narrow stripes, shaped like chevrons, that wrap around each other in a concentric pattern and are bisected by a black dorsal stripe. The chevron pattern is especially distinct on the limbs, where the point of the chevron points dorsally, becoming more acute the further up the limb they climb; they reach a final peak at the shoulders and the withers. On the cranium, chevrons extend dorsally to the cheek, where the pattern becomes more linear. The belly of this zebra is completely white, unlike other zebras. Grevy's zebras are also the largest of all the wild equids and only domestic horses are larger. Grevy's zebras exhibit slight sexual dimorphism; males are usually about 10 percent larger than females. Grevy's zebra foals are born with a coat that has reddish-brown or russet stripes instead of the black of adults. This gradually darkens to black as the zebra ages. A dorsal mane that extends from the top of the head to the base of the tail is present in all young zebras. This mane is erect when an animal is excited and flat when it is relaxed. Adult dental formula is 3/3, 1/1, 4/4, 3/3.

Range mass: 349 to 451 kg.

Range length: 125 to 150 cm.

Average length: 135 cm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger

Like most other species the lifespan of Equus grevyi is longer in captivity than in the wild. In captivity, Equus grevyi usually lives between 22 and 30 years. In the wild, the median age is closer to 12 or 13, although an 18 year old animal has been reported.

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 18 (high) years.

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 30 (high) years.

Typical lifespan

Status: wild: 18 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 12-13 years.

Typical lifespan

Status: captivity: 22 to 30 years.

Grevy's zebras inhabit semi-arid grasslands, filling a niche distinct from that of other members of the genus Equus that live within the same geographical range, such as wild asses (which prefer arid habitats) and plains zebras (which are more dependent on water than Grevy's zebras). They usually prefer arid grasslands or acacia savannas. The most suitable areas have a permanent water source. In recent years, Grevy's zebras have become increasingly concentrated in the south of their range due to habitat loss in the north. During the dry season, when location near a permanent water source is especially important, zebras tend to become more concentrated in territories with permanent water sources. In rainy seasons, they are more dispersed. Areas with green, short grass and medium-dense bush are used by lactating females and bachelors more frequently than non-lactating females or territorial males. Lactating females may trade off forage quantity and safety to access nutrients in growing grass.

Range elevation: 300 to 600 m.

Average elevation: 500 m.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland

Grevy's zebras live in northern Kenya and a few small areas of southern Ethiopia. Historically, Grevy's zebras inhabited Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, and Kenya in East Africa. The last survey in Kenya in 2000 resulted in an estimated population of 2,571. Current estimates place the number of Grevy's zebras in Kenya between 1,838 and 2,319. In Ethiopia, the current population estimate is 126, over a 90% decrease from the estimated 1,900 in 1980. The eastern distribution is north of the Tana River east of Garissa and the Lorian Swamp. In the west, they are found east and north of a line from Mount Kenya to Donyo Nyiro, and east of Lake Turkana to Ethiopia. In Ethiopia, they are found east of the Omo River north to Lake Zwai, southeast to Lake Stephanie and to Marsabit in Kenya.

Biogeographic Regions: ethiopian (Native )

Grevy's zebras are herbivores and grazers with occasional browsing tendencies. They primarily eat tough grasses and forbs but, in the dry season when grasses are not as abundant, leaves can constitute up to 30 percent of their diet. Grevy's zebras can digest many different types and parts of plants that cattle cannot. Grevy's zebras are water dependent and will often migrate to grasslands within daily reach of water. Most Grevy's zebras can survive without water for up to five days, but lactating females must drink at least every other day in order to maintain healthy milk production.

Plant Foods: leaves

Primary Diet: herbivore (Folivore )

Grevy's zebras are large, grazing ungulates that feed on grasses and serve as prey for a number of large predators. They fill a niche left open between arid-habitat loving wild asses and water-dependent plains zebras.

Grevy's zebras have a distinct appearance and are a source of ecotourism interest. Grevy's zebras have been used as food and a source of pelts in the past.

Positive Impacts: body parts are source of valuable material; ecotourism

A 5-year conservation plan of the Kenya Wildlife Services (KWS) was launched on June 25, 2008. This conservation plan aims to recover the population of Grevy's zebras, which declined from 15,000 in the 1970s to just over 2,500 in 2009. The plan suggests the need for a monitoring system to estimate the population size of Equus grevyi, to assess its condition, to track movements, and to determine the causes of mortality. In addition to this, local communities in Kenya are getting more involved in the conservation of Equus grevyi and Ethiopa has held two workshops regarding status and conservation. Equus grevyi was previously listed as a game animal in Kenya and is now being upgraded to a protected animal. It is also listed as protected in Ethiopia, although official protection has been limited.

US Federal List: threatened

CITES: appendix i

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: endangered

No two zebras have the same stripe pattern. Each individual zebra's stripe pattern acts as a type of fingerprint that allows it to be identified accurately by human researchers up to 90% of the time. This, along with scent and individual vocalizations, allow individuals to be recognized by conspecifics.

Scent marking, especially by females, plays a significant role in breeding. Males often sniff the leavings of a female in order to determine if she is in estrous. Males use dung and urine in order to mark their territory.

Males use sounds and visual cues to assert their dominance. They may do this by baring their teeth, flattening their ears, kicking, or biting other males. Territorial males often harass females into breeding with them using these same techniques.

Grevy's zebras are very vocal, though not quite as vocal as plains zebras. Their vocabulary includes several distinct pitches. Individuals often emit these pitches when they are escaping predators or when they are fighting.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic

Other Communication Modes: scent marks

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Equus grevyi individuals can run at speeds of up to 40 mph (64 kph).

A male mates with any females that come into his territory if they are in estrous. Mares are usually polyandrous and mate with one male before switching territories and mating with another, although sometimes mares become monandrous. When a mare stays in a single territory, usually because she desires the resources that are present in that territory, she will stay with a single male and mate only with him.

Mating System: polygynous

Grevy's zebras can mate year round, but the majority of breeding occurs from July to August and September to October. Foals are born after a 13 month gestation period, usually within the rainy months of the year. Peaks usually occur in May and June, the period of long rains, and in November and December, the period of short rains. As birth approaches, females isolate themselves from the herd. Birth normally takes place lying down, with the young's hoofs appearing first, and full emergence in 7 to 8 minutes. If birth begins with the mother standing, it is completed lying down. The newborn frees itself from the amniotic membranes and crawls towards its mother's head. The mother licks it clean and ingests the membranes and some amniotic fluid, which may be important in initiating lactation or the maternal bond. Zebras take an average of 275 days to be weaned. Once weaned, they continue to stay with their mother. Females disperse sooner than males, females disperse at 13 to 18 months and males often stay with their mother for up to 3 years. A newborn Grevy's zebra foal is russet-colored with a long hair crest down its back and belly. At this stage, imprinting occurs. Female zebras keep other zebras at a distance so that the foal can bond with its mother. Newborn foals can walk just 20 minutes after being born and run after an hour, which is a very important survival adaptation for this cursorial, migrating species. Foals nurse heavily for half a year and may take as long as three years to be completely weaned. Females achieve sexual maturity around 3 years of age and males achieve sexual maturity around 6 years of age. Females tend to conceive once every two years.

Breeding interval: Female Grevy's zebras breed about once every two years.

Breeding season: Grevy's zebras can mate year round, but most breeding occurs July through August and October through November.

Range number of offspring: 1 to 1.

Range gestation period: 358 to 438 days.

Average gestation period: 390 days.

Average weaning age: 275 days.

Range time to independence: 1 to 3 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 3 to 4 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 3 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 1 to 7 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 6 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; year-round breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; viviparous

Average birth mass: 40000 g.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Males play little to no role in caring for the young, females are solely responsible for caring for the young. Immediately after childbirth, the foal imprints on the mother and can recognize her distinct scent, appearance, and vocalizations. An imprinted foal will directly follow its mother and can recognize the shape of the stripes on its mother's backside. Until it is weaned, a foal will follow its mother and learn to mimic all of her behavior. Female foals become independent from their mothers sooner than male foals, even though both genders are weaned at around the same time. Males often remain with their birth herd until they reach three years of age and females have been known to separate at just 13 months of age.

Parental Investment: precocial ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-independence (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); post-independence association with parents

Grévy's zebra (Equus grevyi), also known as the imperial zebra, is the largest living wild equid and the most threatened of the three species of zebra, the other two being the plains zebra and the mountain zebra. Named after Jules Grévy, it is found in parts of Kenya and Ethiopia. Superficially, Grévy's zebras’ physical features can help to identify it from the other zebra species; their overall appearance is slightly closer to that of a mule, compared to the more “equine” (horse) appearance of the plains and mountain zebras. Compared to other zebra species, Grévy’s are the tallest; they have mule-like, larger ears, and have the tightest stripes of all zebras. They have distinctively erect manes, and more slender snouts.

The Grévy's zebra live in semi-arid savanna, where they feed on grasses, legumes, and browse, such as acacia; they can survive up to five days without water. They differ from the other zebra species in that they do not live in a harem, and they maintain few long-lasting social bonds. Stallion territoriality and mother–foal relationships form the basis of the social system of the Grévy's zebra. Despite a handful of zoos and animal parks around the world having had successful captive-breeding programs, in its native home this zebra is listed by the IUCN as endangered. Its population has declined from 15,000 to 2,000 since the 1970s. In 2016, the population was reported to be “stable”; however, as of 2020, the wild numbers are still estimated at only around 2,250 animals, in part due to anthrax outbreaks in eastern Africa.[6]

The Grévy's zebra was first described by French naturalist Émile Oustalet in 1882. He named it after Jules Grévy, then president of France, who, in the 1880s, was given one by the government of Abyssinia. Traditionally, this species was classified in the subgenus Dolichohippus with plains zebra and mountain zebra in Hippotigris.[7] Groves and Bell (2004) place all three species in the subgenus Hippotigris.[8]

Fossils of zebra-like equids have been found throughout Africa and Asia in the Pliocene and Pleistocene deposits.[7] Notable examples include E. sanmeniensis from China, E. cautleyi from India, E. valeriani from central Asia and E. oldowayensis from East Africa.[7] The latter, in particular is very similar to the Grévy's zebra and may have been its ancestor.[7] The modern Grévy's zebra arose in the Middle Pleistocene.[9] Zebras appear to be a monophyletic lineage[10][11][12] and recent (2013) phylogenies have placed Grévy's zebra in a sister taxon with the plains zebra.[10] In areas where Grévy's zebras are sympatric with plains zebras, the two may gather in same herds[13] and fertile hybrids do occur.[14]

The Grévy's zebra is the largest of all wild equines. It is 2.5–2.75 m (8.2–9.0 ft) in head-body with a 55–75 cm (22–30 in) tail, and stands 1.45–1.6 m (4.8–5.2 ft) high at the withers. These zebras weigh 350–450 kg (770–990 lb).[15] Grévy's zebra differs from the other two zebras in its more primitive characteristics.[16]: 147 It is particularly mule-like in appearance; the head is large, long, and narrow with elongated nostril openings;[16]: 147 the ears are very large, rounded, and conical and the neck is short but thick.[17] The zebra's muzzle is ash-grey to black in colour with the lips having whiskers. The mane is tall and erect; juveniles have a mane that extends to the length of the back and shortens as they reach adulthood.[17]

As with all zebra species, the Grévy's zebra's pelage has a black and white striping pattern. The stripes are narrow and close-set, being broader on the neck, and they extend to the hooves.[17] The belly and the area around the base of the tail lack stripes and are just white in color, which is unique to the Grévy's zebra. Foals are born with brown and white striping, with the brown stripes darkening as they grow older.[17]

The Grévy's zebra largely inhabits northern Kenya, with some isolated populations in Ethiopia.[16]: 147 [17] It was extirpated from Somalia and Djibouti and its status in South Sudan is uncertain.[3] It lives in Acacia-Commiphora bushlands and barren plains.[13] Ecologically, this species is intermediate between the arid-living African wild ass and the water-dependent plains zebra.[13][16]: 147 Lactating mares and non-territorial stallions use areas with green, short grass and medium, dense bush more often than non-lactating mares and territorial stallions.[18]

Grévy's zebras rely on grasses, legumes, and browse for nutrition.[17] They commonly browse when grasses are not plentiful.[13][19] Their hindgut fermentation digestive system allows them to subsist on diets of lower nutritional quality than that necessary for ruminant herbivores. Grevy's zebras can survive up to a week without water, but will drink daily when it is plentiful.[20] They often migrate to better watered highlands during the dry season.[13] Mares require significantly more water when they are lactating.[21] During droughts, the zebras will dig water holes and defend them.[13] The Grévy's zebra's main predator is the lion, but adults can be hunted by spotted hyenas. African hunting dogs, cheetahs and leopards almost never attack adults, even in desperate times, but sometimes prey on young animals, although mares are fiercely protective of their young.[17] In addition, they are susceptible to various gastro-intestinal parasites, notably of the genus Trichostrongylus.[22]

Adult stallions mostly live in territories during the wet seasons but some may stay in them year round if there's enough water left.[13] Stallions that are unable to establish territories are free-ranging[16]: 151 and are known as bachelors. Mares, young and non-territorial stallions wander through large home ranges. The mares will wander from territory to territory preferring the ones with the highest-quality food and water sources.[23] Up to nine stallions may compete for a mare outside of a territory.[17] Territorial stallions will tolerate other stallions who wander in their territory. However, when an oestrous mare is present the territorial stallion keeps other stallions at bay.[13][16]: 151 Non-territorial stallions might avoid territorial ones because of harassment.[18] When mares are not around, a territorial stallion will seek the company of other stallions. The stallion shows his dominance with an arched neck and a high-stepping gait and the least dominant stallions submit by extending their tail, lowering their heads and nuzzling their superior's chest or groin.[16]: 151

Zebras produce numerous sounds and vocalisations. When alarmed, they produce deep, hoarse grunts. Whistles and squeals are also made when alarmed, during fights, when scared or in pain. Snorts may be produced when scared or as a warning. A stallion will bray in defense of his territory, when driving mares, or keeping other stallions at bay. Barks may be made during copulation and distressed foals will squeal.[17] The call of the Grévy's zebra has been described as "something like a hippo's grunt combined with a donkey's wheeze".[13] To get rid of flies or parasites, they roll in dust, water or mud or, in the case of flies, they twitch their skin. They also rub against trees, rocks and other objects to get rid of irritations such as itchy skin, hair or parasites.[17] Although Grévy's zebras do not perform mutual grooming, they do sometimes rub against a conspecific.[17]

Grévy's zebras can mate and give birth year round, but most mating takes place in the early rainy seasons and births mostly take place in August or September after the long rains.[17] An oestrous mare may visit as many as four territories a day[23] and will mate with the stallions in them. Among territorial stallions, the most dominant ones control territories near water sources, which mostly attract mares with dependant foals,[24] while more subordinate stallions control territories away from water with greater amounts of vegetation, which mostly attract mares without dependant foals.[24]

The resident stallions of territories will try to subdue the entering mares with dominance rituals and then continue with courtship and copulation.[13] Grévy's zebra stallions have large testicles and can ejaculate a large amount of semen to replace the sperm of other males.[23] This is a useful adaptation for a species whose mares mate polyandrously. Bachelors or outside territorial stallions sometimes "sneak" copulation of mares in another stallion's territory.[23] While mare associations with individual stallions are brief and mating is promiscuous, mares who have just given birth will reside with one stallion for long periods and mate exclusively with that stallion.[23] Lactating females are harassed by stallions more often than non-lactating ones and thus associating with one male and his territory provides an advantage as he will guard against other males.[25]

Gestation of the Grévy's zebra normally lasts 390 days,[17] with a single foal being born. A new-born zebra will follow anything that moves, so new mothers prevent other mares from approaching their foals while imprinting their own striping pattern, scent and vocalisation on them.[17] Mares with young foals may gather into small groups.[21] Mares may leave their foals in "kindergartens" while searching for water.[21] The foals will not hide, so they can be vulnerable to predators.[13] However, kindergartens tend to be protected by an adult, usually a territorial stallion.[21] A mare with a foal stays with one dominant territorial stallion who has exclusive mating rights to her. While the foal may not be his, the stallion will look after it to ensure that the mare stays in his territory.[26] To adapt to a semi-arid environment, Grévy's zebra foals have longer nursing intervals and wait until they are three months old before they start drinking water.[21] Although offspring become less dependent on their mothers after half a year, associations with them continue for up to three years.[13]

The Grévy's zebra was known to the Europeans in antiquity and was used by the Romans in circuses.[7] It was subsequently forgotten in the Western world for a thousand years.[7] In the seventeenth century, the king of Shoa (now central Ethiopia) exported two zebras; one to the Sultan of Turkey and another to the Dutch governor of Jakarta.[7] A century later, in 1882, the government of Abyssinia sent one to French president Jules Grévy. It was at that time that the animal was recognised as its own species and named in Grévy's honour.[7]

The Grévy's zebra is considered endangered.[3] Its population was estimated to be 15,000 in the 1970s and by the early 21st century the population was lower than 3,500, a 75% decline.[27]: 11 In 2008 it was estimated that there are less than 2,500 Grévy's zebras still living in the wild, further declining to fewer than 2,000 mature individuals in 2016. Nonetheless, the Grévy's zebra population trend was considered stable as of 2016.[3]

There are also an estimated 600 Grévy's zebras in captivity.[27]: 20 Captive herds have been known to thrive, like at White Oak Conservation in Yulee, Florida, United States, where more than 70 foals have been born. There, research is underway in partnership with the Conservation Centers for Species Survival on semen collection and freezing and on artificial insemination.[28]

The Grévy's zebra is legally protected in Ethiopia. In Kenya, it is protected by the hunting ban of 1977. In the past, Grévy's zebras were threatened mainly by hunting for their skins which fetched a high price on the world market. However, hunting has declined and the main threat to the zebra is habitat loss and competition with livestock. Cattle gather around watering holes and the Grévy's zebras are fenced from those areas.[27]: 17 Community-based conservation efforts have shown to be the most effective in preserving Grévy's zebras and their habitat. Less than 0.5% of the range of the Grévy's zebra is in protected areas. In Ethiopia, the protected areas include Aledeghi Wildlife Reserve, Yabelo Wildlife Sanctuary, Borana National Park, and Chelbi Sanctuary. In Kenya, important protected areas include the Buffalo Springs, Samburu and Shaba National Reserves and the private and community land wildlife conservancies in Isiolo, Samburu and the Laikipia Plateau.[3]

The mesquite plant was introduced into Ethiopia around 1997 and is endangering the zebra's food supply. An invasive species, it is replacing the two grass species, Cenchrus ciliaris and Chrysopogon plumulosus, which the zebras eat for most of their food.[29][30]

Grévy's zebra (Equus grevyi), also known as the imperial zebra, is the largest living wild equid and the most threatened of the three species of zebra, the other two being the plains zebra and the mountain zebra. Named after Jules Grévy, it is found in parts of Kenya and Ethiopia. Superficially, Grévy's zebras’ physical features can help to identify it from the other zebra species; their overall appearance is slightly closer to that of a mule, compared to the more “equine” (horse) appearance of the plains and mountain zebras. Compared to other zebra species, Grévy’s are the tallest; they have mule-like, larger ears, and have the tightest stripes of all zebras. They have distinctively erect manes, and more slender snouts.

The Grévy's zebra live in semi-arid savanna, where they feed on grasses, legumes, and browse, such as acacia; they can survive up to five days without water. They differ from the other zebra species in that they do not live in a harem, and they maintain few long-lasting social bonds. Stallion territoriality and mother–foal relationships form the basis of the social system of the Grévy's zebra. Despite a handful of zoos and animal parks around the world having had successful captive-breeding programs, in its native home this zebra is listed by the IUCN as endangered. Its population has declined from 15,000 to 2,000 since the 1970s. In 2016, the population was reported to be “stable”; however, as of 2020, the wild numbers are still estimated at only around 2,250 animals, in part due to anthrax outbreaks in eastern Africa.