en

names in breadcrumbs

Kokkolitoforidlər (от q.yun. κόκκος — buğdacıq, λίθος — daş, φορέω — aparıram) — birhüceyrəli plankton yosunlar qrupu. Kokkolitoforidlər nanoplanktonların əsas hissəsini (98%) təşkil edir.

Els Cocolitòfors (coccolithophoridae) són algues unicel·lulars, protists i fitoplanctòniques pertanyents a diverses divisions botàniques d'haptòfits. Es caracteritzen per tenir plaques o escates de carbonat de calci de funcionalitat incerta que s'anomenen cocòlits (nanoplàncton calcari), importants com a microfòssils en micropaleontologia. Els cocolitòfors són pràcticament exclusius d'hàbitats marins i es troben en grans quantitats en la zona il·luminada (zona eufòtica). Un exemple de cocolitòfor global i dominant és Emiliania huxleyi.

La forma dels cocolitòfors és en cèl·lules esfèriques d'uns 15–100 micròmetres de diàmetre, tancades en plaques calacàries, cocòlits, d'uns 2–25 micròmetres de diàmetre.

Els Cocolitòfors (coccolithophoridae) són algues unicel·lulars, protists i fitoplanctòniques pertanyents a diverses divisions botàniques d'haptòfits. Es caracteritzen per tenir plaques o escates de carbonat de calci de funcionalitat incerta que s'anomenen cocòlits (nanoplàncton calcari), importants com a microfòssils en micropaleontologia. Els cocolitòfors són pràcticament exclusius d'hàbitats marins i es troben en grans quantitats en la zona il·luminada (zona eufòtica). Un exemple de cocolitòfor global i dominant és Emiliania huxleyi.

La forma dels cocolitòfors és en cèl·lules esfèriques d'uns 15–100 micròmetres de diàmetre, tancades en plaques calacàries, cocòlits, d'uns 2–25 micròmetres de diàmetre.

Kokolitky (Coccolithophorida, Coccolithophyceae) jsou skupina řas řazených dnes do kmene Haptophyta, a to zejména do řádů Isochrysidales a Coccolithales. Někdy jsou pojímány jako přirozená monofyletická skupina,[1] v jiných systémech nejsou vůbec z taxonomického hlediska uvedeny.[2]

Jejich společným znakem je tvorba drobných destiček či šupinek z kalcitu (či vzácně aragonitu), označovaných jako kokolity. Tyto šupinky jsou vyneseny na povrch buňky a tvoří poměrně souvislý obal kolem celé buňky. Jsou významnou složkou fytoplanktonu v mořích a jsou tedy schopné fotosyntézy. V geologickém záznamu o nich máme doklady od triasu, ačkoliv se předpokládá výskyt již v siluru.[3] Známým zástupcem je Emiliana huxleyi.

Kokolitky jsou silně citlivé na změny podmínek prostředí, jako je teplota vody a slanost. Díky této vlastnosti a bohatému výskytu ve fosilních záznamech se fosilizované kokolitky staly důležitým indikátorem, využívaným v paleoklimatologii i k řešení problémů stratigrafie.

Kokolitky (Coccolithophorida, Coccolithophyceae) jsou skupina řas řazených dnes do kmene Haptophyta, a to zejména do řádů Isochrysidales a Coccolithales. Někdy jsou pojímány jako přirozená monofyletická skupina, v jiných systémech nejsou vůbec z taxonomického hlediska uvedeny.

Jejich společným znakem je tvorba drobných destiček či šupinek z kalcitu (či vzácně aragonitu), označovaných jako kokolity. Tyto šupinky jsou vyneseny na povrch buňky a tvoří poměrně souvislý obal kolem celé buňky. Jsou významnou složkou fytoplanktonu v mořích a jsou tedy schopné fotosyntézy. V geologickém záznamu o nich máme doklady od triasu, ačkoliv se předpokládá výskyt již v siluru. Známým zástupcem je Emiliana huxleyi.

Kokolitky jsou silně citlivé na změny podmínek prostředí, jako je teplota vody a slanost. Díky této vlastnosti a bohatému výskytu ve fosilních záznamech se fosilizované kokolitky staly důležitým indikátorem, využívaným v paleoklimatologii i k řešení problémů stratigrafie.

Kalkflagellater (eller coccolithophorider) er gulalger. Fytoplankton og nanoplankton; encellede havlevende organismer i størrelsen 15-100 mikrometer med en overflade af kokkolitter, kalkplader i størrelsen 2-25 mikrometer. Fortidige kalkflagellaters kokkoliter udgør en stor del af kridtet i Danmarks undergrund.

Kalkflagellater (eller coccolithophorider) er gulalger. Fytoplankton og nanoplankton; encellede havlevende organismer i størrelsen 15-100 mikrometer med en overflade af kokkolitter, kalkplader i størrelsen 2-25 mikrometer. Fortidige kalkflagellaters kokkoliter udgør en stor del af kridtet i Danmarks undergrund.

Die Coccolithophorida (auch Coccolithales oder Coccolithophorales, deutsch: Kalkflagellaten) sind eine systematische Gruppe (Taxon) komplexer einzelliger Algen aus der übergeordneten Gruppe Haptophyta. Sie zeichnen sich dadurch aus, dass der organische Zellkörper von einer Kugel aus Calciumcarbonat-Plättchen, der Coccosphäre, umschlossen ist. Die einzelnen Kalkplättchen werden Coccolithen genannt und bestehen stets aus dem Mineral Calcit. Mit einer Größe von oft weniger als 20 µm werden Kalkflagellaten zum kalkigen Nannoplankton gezählt. Aus einigen Epochen der jüngeren Erdgeschichte sind Kalksteine überliefert, die fast ausschließlich aus Coccolithen bestehen, so auch das Kreidegestein, nach dem die Kreidezeit benannt ist.

Der Name Coccolithophorida geht zurück auf Coccolithophora Lohmann, einen heute ungültigen Gattungsnamen (Synonym von Coronosphaera[1]). Da früheren Bearbeitern noch unklar war, ob sie die Gruppe dem Pflanzenreich oder dem Tierreich (als aberrante „Flagellaten“) zuordnen sollten, wurden sie in beiden Gruppen, mit voneinander abweichenden Nomenklaturregeln, beschrieben. Dementsprechend wurde zuerst der Name Coccolithophoridae (eine Familie, unter Anwendung des ICZN für „Tiere“), später Coccolithophoraceae unter Anwendung des ICBN, geprägt. Später wurde auf dieser Grundlage eine Ordnung Coccolithophorales aufgestellt[2], die später Coccosphaerales genannt wurde (in die Klasse Prymnesiophyceae gestellt).

Die Kalkflagellaten traten in der Erdgeschichte gesteinsbildend auf. Sie müssen sich in diesen Zeiten extrem stark im obersten Teil der Wassersäule der Schelfmeere vermehrt haben und nach Ende ihres Lebenszyklus auf den Meeresgrund abgesunken (sedimentiert) sein. Aus dem resultierenden Sediment, dem sogenannten Coccolithenschlamm, ist nachfolgend durch Diagenese Kalkstein gebildet worden. Coccolithen bilden unter anderem einen wesentlichen Bestandteil der Kreidefelsen von Rügen, Møn und der südenglischen Kreideküste bei Dover. In einem Kubikzentimeter Kreide sind rund 800 Millionen Coccolithen enthalten. Erste sichere Funde der Coccolithophoriden stammen aus der Trias. Die größte Verbreitung und Formenvielfalt erreichten sie in der Kreide. Das große Massenaussterben am Ende dieses Zeitalters verursachte einen starken Rückgang dieser Algen. Einen neuen Höhepunkt der Formenvielfalt und Verbreitung erreichten sie vor ca. 50 Millionen Jahren im Eozän. Die rezente Gattung Braarudosphaera lässt sich bis in die Kreide zurückverfolgen.

Für die Wissenschaft sind sie von Bedeutung, da man anhand ihrer fossilen Reste in den Sedimenten sowohl auf das Alter dieser Ablagerungen, als auch auf die ehemals herrschenden Umweltbedingungen schließen kann.

Coccolithophoriden werden von Viren parasitiert, wenngleich es mit Emiliania huxleyi virus 86 (EhV-86) erst eine Viren-Spezies gibt, die dies nachweislich tut (Stand 2019). Diese Spezies, bei der es sich um ein Riesenvirus aus der Familie Phycodnaviridae handelt, wird aufgrund ihrer Wirtsspezies der Gattung Coccolithovirus zugeordnet.

Die Coccolithophorida (auch Coccolithales oder Coccolithophorales, deutsch: Kalkflagellaten) sind eine systematische Gruppe (Taxon) komplexer einzelliger Algen aus der übergeordneten Gruppe Haptophyta. Sie zeichnen sich dadurch aus, dass der organische Zellkörper von einer Kugel aus Calciumcarbonat-Plättchen, der Coccosphäre, umschlossen ist. Die einzelnen Kalkplättchen werden Coccolithen genannt und bestehen stets aus dem Mineral Calcit. Mit einer Größe von oft weniger als 20 µm werden Kalkflagellaten zum kalkigen Nannoplankton gezählt. Aus einigen Epochen der jüngeren Erdgeschichte sind Kalksteine überliefert, die fast ausschließlich aus Coccolithen bestehen, so auch das Kreidegestein, nach dem die Kreidezeit benannt ist.

Coccolithophore ili kokolitoforide[1] su jednoćelijske, eukariotske fitoplanktonske alge. Pripadaju ili carststvu Protista, prema Whittakerovoj klasifikaciju od pet carstava ili kladusu Hacrobia, prema novijem sistemu biološke klasifikacije. Unutar Hacrobia, kokolitoforide su u koljenu ili diviziji Haptophyta, razred Prymnesiophyceae ili Coccolithophyceae.[2]

Kokolitoforoide se odlikuju posebnim kalcij-karbonatnim pločama (ili ljuskama) nejasne funkcije zvane kokoliti, koje su također važni u paleontologija mikrofosilima. Međutim, postoje vrste Prymnesiophyceae kojima nedostaju kokoliti (npr. u rodu Prymnesium), pa nije svaki pripadnik Prymnesiophyceae kokolitofoforid.[3] Kokolitoforide su gotovo isključivo morski organizmi i nalaze se u velikom broju u zoni sunčevog zračenja okeana.

Najzastupljenija vrsta kokolitoforida je Emiliania huxleyi iz reda Isochrysidales , porodica Noëlaerhabdaceae.[2] Nađene su u umjerenim suptropskim i tropskim okeanima.[4] To je čini važanim dijelo baze planktona velikog dijela morskih mreža istrane. To je ujedno i najbrže rastuća kokolitofora u laboratorijskim kulturama.[5] Intenzivno je proučavana u pojavama cvjetanja koje nastaju u vodama iscrpljenim hranjivim tvarima nakon ljetne reformacije termoklina,[6][7] i za proizvodnju molekula poznatih kao alkenoni koje obično koriste naučnici o zemlji kao sredstvo za procjenu prošlosti temperatura morske površine.[8]

Kokolitoride su od posebnog interesa za one koji proučavaju globalno klimatske promjene jer kako kiselost okeana raste, njihovi kokoliti mogu postati još važniji kao otapanje ugljika.[9] Nadalje, koriste se strategije upravljanja kako bi se spriječilo cvjetanje mora u vezi s eutrofikacijom, jer ono dovodi do smanjenja protoka hranjivih tvari do nižih nivoa okeana.[10]

Kokolitoforide su sferne ćelije veličine oko 5–100 mikrometra, okružene krečnjačkim pločicama koje se zovu kokoliti, a koje su dužine oko 2–25 mikrometra. Svaka ćelija sadrži dva smeđa hloroplasta koji okružuju ćelijsko jedro.[11]

Svaki jednoćelijski plankton zatvoren je u svoj skup kokolita, kalcificiranih ljuski, koje čine njegov egzoskelet ili kokosferu.[12] Kokoliti nastaju unutar ćelije i dok neke vrste održavaju jedan sloj tokom života samo proizvodeći nove kokolite dok ćelija raste, druge ih neprekidno proizvode i odbacujuaju. Primarni sastojak kokolita je kalcij-karbonat ili kreda. Kalcij-karbonat je transparentan, tako da fotosintetska aktivnost organizma nije ugrožena njegovom ugradnjom u kokosferu.[13]

Stvaranje kokolita: Kokoliti nastaju postupkom biomineralizacija poznatim kao kokolitogeneza.[11] Općenito, kalcifikacija kokolita nastaje u prisustvu svjetlosti, a ove se ljuskice proizvode mnogo više tokom eksponencijalne faze rasta nego u stacionarnoj fazi.[14] Iako još nije u potpunosti shvaćen, proces biomineralizacije je strogo reguliran kalcijskom signalizacijom. Formiranje kalcita započinje u Golgijevom aparatu gdje proteinske matrice ukidaju nastanak kristala CaCO3 i složene kisele polisaharidne kontrole oblika i rasta ovih kristala.[15][16]

Tipovi strukture: ovisno o stadiju fitoplanktona u životnom ciklusu, mogu se formirati dvije različite varijante kokolita. Holokokoliti se proizvode samo u haploidnoj fazi, bez radijalne simetrije, a sastoje se od stotina do hiljada sličnihsićušnih (oko 0,1 µm) rombnih kristala kalcita. Smatra se da se ovi kristali bar djelomično formiraju izvan ćelije. Heterokokoliti se javljaju samo u diploidnoj fazi, imaju radijalnu simetriju i sastoje se od relativno malo složenih kristalnih jedinica (manje od 100). Iako su rijetke, primijećene su kombinirane kokosfere koje sadrže i holokokoliste i heterokokoliste kod planktona koji imaju prijelazne životne cikluse kokolitora. Konačno, kokosfere nekih vrsta su vrlo modificirane različitim dodacima izrađenim od specijaliziranih kokolita.[17]

Funkcija kokosfere je nejasna, ali su pretpostavljene mnoge potencijalne uloge. Najočiglednije kokoliti mogu zaštititi fitoplankton od grabežljivaca. Također se čini da im pomaže da stvore stabilniji pH. Tokom fotosinteze ugljik-dioksid se uklanja iz vode, čineći ga osnovnim. Također kalcifikacija uklanja ugljik-dioksid, ali hemija iza njega vodi u suprotnu pH reakciju; to čini vodu kiselijom. Kombinacija fotosinteze i kalcifikacije stoga se međusobno izjednačavaju u vezi s promjenama pH.[18] Pored toga, ti egzoskeleti mogu pružiti prednost u proizvodnji energije, jer kokolitogeneza izgleda da je jako vezana sa fotosintezom. Organska precipitacija kalcij-karbonata iz otopine bikarbonata stvara slobodni ugljik-dioksid direktno unutar ćelijskog tijela alge, a ovaj dodatni izvor plina je tada dostupan kokolitoforama za fotosintezu. Pretpostavlja se da oni mogu pružati barijeru poput ćelijskog zida za izolaciju unutarćelijske hemije iz morskog okoliša.[19] Preciznija, odbrambena svojstva kokolita mogu uključivati zaštitu od osmotskih promjena, hemijskog ili mehaničkog udara i svjetlosti kratke talasne dužine.[20] Predloženo je također i da dodana težina više slojeva kokolita omogućava organizmu da potone ka niže i više hranjivim slojevima vode i obrnuto, da kokoliti dodaju uzgon, zaustavljajući ćeliju da ne potone na opasne dubine.[21] Za kokolitne dodatke također je predloženo da imaju nekoliko funkcija, poput inhibiranja ishrane za zooplankton.[17]

Kokoliti su glavna komponenta krede, stijena kasne krede koje su široko rasprostranjena u južnoj Engleskoj i tvore Bijele litice Dovera, te drugih sličnih stijena u mnogim drugim dijelovima svijeta.[7] Sada su sedimentirani kokoliti glavni sastojak karbonatnih ooza koji prekrivaju do 35% dna okeana, a mjestimično su kilometarske debljine.[15] Zbog bogatstva i širokog geografskog raspona, kokoliti koji čine slojeve ovih jajolikih i kredastih sedimenata koji se formiraju tokom taloženja služe kao vrijedni mikrofosili.

Zatvorena u svakoj kokosferi, nalazi se jedna ćelija sa membranom vezanom sa organelama. Dva velika hloroplasta sa smeđim pigmentom nalaze se na obje strane ćelije i okružuju ćelijsko jedro, mitohondrije, golgijev aparat, endoplazmatski retikulum i ostale organele. Svaka ćelija također ima dvije bičaste strukture, koje sudjeluju ne samo u pokretljivosti, već i u mitozi i stvaranju citoskeleta.[22] Kod nekih vrsta prisutna je i funkcionalna ili zakržljala [haptonema].[20] Ova struktura, koja je karakteristične za haptofite, zavija se i odmotava, kao odgovor na podražaje iz okoline. Iako je slabo shvaćena, predloženo je da je uključena u hvatanje plijena.[22]

Kokolitoforide se javljaju širom svjetskog okeana. Njihova distribucija varira okomito po slojevima u okeanu i geografski po različitim vremenskim zonama.[23] Dok se većina modernih kokholitorida može nalaziti u njihovim pripadajućim stratifikovanim oligotrofnim uslovima, najbrojnija njihova područja, u kojima postoji najveća raznolikost vrsta nalaze su u suptropskim zonama sa umjerenom klimom.[24] Dok su temperatura vode i količina intenziteta svjetlosti koja uđe u površinu vode utjecajniji faktori u određivanju gdje se vrste nalaze, okeanske struje također mogu odrediti lokaciju na kojoj se nalaze određene vrste kokolitofora.[25]

Iako se pokretljivost i formiranje kolonija razlikuju u skladu s životnim ciklusom različitih vrsta kokolitofora, često postoji alternacija između pokretne, haploidne faze i nepokretne diploidne faze. U obje faze raspršivanje organizma u najvećoj mjeri je posljedica okeanski struja i obrazaca cirkulacije.[15]

U Tihoom okeanu identificirano je otprilike 90 vrsta sa šest zasebnih zona koje se odnose na različite pacifičke struje koje sadrže jedinstvene grupe različitih vrsta kokolitofor.[26] Najveća raznolikost koktolitofora u Tihom okeanu bila je u područjukoje se smatra centralnom sjevernom zonom, a to je područje između 30oN i 5oN, sačinjeno od sjeverne ekvatorske struje i ekvatorake protivstruje. Ove dvije struje kreću se u suprotnim smjerovima, prema istoku i zapadu, omogućujući snažno miješanje voda i velikom broju vrsta da nasele ovo područje.[26]

U Atlantskom okeanu najbrojnije su vrste Emiliania huxleyi i Florisphaera profunda s manjim koncentracijama vrsta Umbellosphaera nepravilis, Umbellosphaera tenuis i različitih vrsta roda Gephyrocapsa.[26] Na količinu dubokomorskih oblika utiču lanci ishrane i termokline nastanjenih kokkolitofornih vrsta. Brojnost tih kokolitofora povećavaju u obilju kada su nutritijenti i termoklina duboki, a opada kada su plitki.[27]

Kompletna raspodjela kokolitofora danas nije poznata, a neke regije, poput Indijskog okeana, nisu tako poznate kao ostale lokacije u Tihom i Atlantskom okeanu. Također je vrlo teško objasniti raspodjelu zbog višestruko promjenjivih faktora koji uključuju svojstva okeana, poput obalnog i ekvatorijskih uzlaznih struja, frontalnih sistema, bentoskog okruženja, jedinstvene okeanske topografije i džepova izoliranih visokih ili niskih temperatura vode.[17]

Koktolitofore su jedan od najizdašnijih primarnih proizvođača u okeanu. Kao takvi, oni uveliko doprinose primarnoj produktivnosti tropskog i suptropskog okeana, međutim, upravo onoliko koliko ih je još ostalo.[28]

Odnos koncentracija dušika, fosfora i silikata u pojedinim područjima okeana diktira natjecateljska+u dominaciju unutar fitoplanktonskih zajednica. Svaki omjer u osnovi daje izglede u korist bilo diatomeja ili drugih skupina fitoplanktona, kao što su kokolitofore. Nizak omjer silikata, dušika i fosfora omogućuje kokolitoforama da nadmaše ostale vrste fitoplanktona; međutim, dijatomeje su nadmašene kad su silikati u odnosu na fosfor prema dušiku visoki. Porast poljoprivrednih procesa dovodi do eutrofikacije voda, pa se javlja cvjetanje kokolitopfora u ovim okruženjima s visokim sadržajem dušika i fosfora, a niskim silikatima.

Kalcit u kalcij-karbonatu omogućava kokolitima da rasprše više svjetlosti nego što apsorbiraju. To ima dvije važne posljedice:

U prvom slučaju, visoka koncentracija kokolitoforaa dovodi do istodobnog porasta temperature površinske vode i smanjenja temperature dubljih voda. To rezultira s više slojevitosti u vodenom stubu i smanjenje vertikalnog miješanja hranjivih sastojaka.[29] Međutim, nedavna studija procijenila je da je sveukupni učinak kokolitofora na povećano zračenje okeana manji od učinka antropogenih faktora. Stoga je sveukupni rezultat velikog cvjetanja kokolitofora smanjenje produktivnosti vodenih stubova, a ne doprinosi globalnom zagrijavanju.

Njihovi grabežljivci uključuju zajedničke grabežljivce sveukupnog itoplanktona, uključujući male ribe, zooplankton i larve školjki. Virusi specifični za ovu vrstu izolirani su s nekoliko lokacija širom svijeta i čini se da imaju glavnu ulogu u dinamici proljetnog cvjetanja.

Nisu zabilježeni okolišni dokazi o toksičnosti kokolitofora, ali pripadaju razredu Prymnesiophyceae koji sadrži redove s otrovnim vrstama. Otrovne su vrste pronađene u rodovima Prymnesium Massart i Chrysochromulina Lackey. Otkriveno je da pripadnici roda "Prymnesium" proizvode hemolitske spojeve, agense odgovorne za toksičnost. Neke od tih otrovnih vrsta odgovorne su za veliko ubijanje ribe i mogu se nakupljati u organizmima kao što su školjke, prenoseći otrov kroz prehrambeni lanac. U laboratorijskim ispitivanjima toksičnosti pripadnika okeanskih rodova kokolitofora "Emiliania, Gephyrocapsa, Calcidiscus" i "Coccolithus" pokazalo se da nisu toksični, kao što su to bile i vrste obalnog roda "Hymenomonas", ali i nekoliko vrsta "Pleurohrizisa" i "Jomonlithus", oba obalna roda bila su toksična za rod "Artemia".

Coccolithophore ili kokolitoforide su jednoćelijske, eukariotske fitoplanktonske alge. Pripadaju ili carststvu Protista, prema Whittakerovoj klasifikaciju od pet carstava ili kladusu Hacrobia, prema novijem sistemu biološke klasifikacije. Unutar Hacrobia, kokolitoforide su u koljenu ili diviziji Haptophyta, razred Prymnesiophyceae ili Coccolithophyceae.

Kokolitoforoide se odlikuju posebnim kalcij-karbonatnim pločama (ili ljuskama) nejasne funkcije zvane kokoliti, koje su također važni u paleontologija mikrofosilima. Međutim, postoje vrste Prymnesiophyceae kojima nedostaju kokoliti (npr. u rodu Prymnesium), pa nije svaki pripadnik Prymnesiophyceae kokolitofoforid. Kokolitoforide su gotovo isključivo morski organizmi i nalaze se u velikom broju u zoni sunčevog zračenja okeana.

Najzastupljenija vrsta kokolitoforida je Emiliania huxleyi iz reda Isochrysidales , porodica Noëlaerhabdaceae. Nađene su u umjerenim suptropskim i tropskim okeanima. To je čini važanim dijelo baze planktona velikog dijela morskih mreža istrane. To je ujedno i najbrže rastuća kokolitofora u laboratorijskim kulturama. Intenzivno je proučavana u pojavama cvjetanja koje nastaju u vodama iscrpljenim hranjivim tvarima nakon ljetne reformacije termoklina, i za proizvodnju molekula poznatih kao alkenoni koje obično koriste naučnici o zemlji kao sredstvo za procjenu prošlosti temperatura morske površine.

Kokolitoride su od posebnog interesa za one koji proučavaju globalno klimatske promjene jer kako kiselost okeana raste, njihovi kokoliti mogu postati još važniji kao otapanje ugljika. Nadalje, koriste se strategije upravljanja kako bi se spriječilo cvjetanje mora u vezi s eutrofikacijom, jer ono dovodi do smanjenja protoka hranjivih tvari do nižih nivoa okeana.

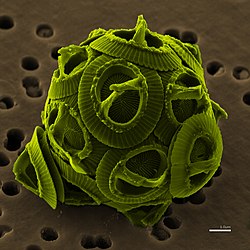

Coccolithophores, or coccolithophorids, are single-celled organisms which are part of the phytoplankton, the autotrophic (self-feeding) component of the plankton community. They form a group of about 200 species, and belong either to the kingdom Protista, according to Robert Whittaker's five-kingdom system, or clade Hacrobia, according to a newer biological classification system. Within the Hacrobia, the coccolithophores are in the phylum or division Haptophyta, class Prymnesiophyceae (or Coccolithophyceae). Coccolithophores are almost exclusively marine, are photosynthetic, and exist in large numbers throughout the sunlight zone of the ocean.

Coccolithophores are the most productive calcifying organisms on the planet, covering themselves with a calcium carbonate shell called a coccosphere. However, the reasons they calcify remains elusive. One key function may be that the coccosphere offers protection against microzooplankton predation, which is one of the main causes of phytoplankton death in the ocean.[1]

Coccolithophores are ecologically important, and biogeochemically they play significant roles in the marine biological pump and the carbon cycle.[2][1] They are of particular interest to those studying global climate change because, as ocean acidity increases, their coccoliths may become even more important as a carbon sink.[3] Management strategies are being employed to prevent eutrophication-related coccolithophore blooms, as these blooms lead to a decrease in nutrient flow to lower levels of the ocean.[4]

The most abundant species of coccolithophore, Emiliania huxleyi, belongs to the order Isochrysidales and family Noëlaerhabdaceae.[5] It is found in temperate, subtropical, and tropical oceans.[6] This makes E. huxleyi an important part of the planktonic base of a large proportion of marine food webs. It is also the fastest growing coccolithophore in laboratory cultures.[7] It is studied for the extensive blooms it forms in nutrient depleted waters after the reformation of the summer thermocline.[8][9] and for its production of molecules known as alkenones that are commonly used by earth scientists as a means to estimate past sea surface temperatures.[10]

Coccolithophores (or coccolithophorids, from the adjective[11]) form a group of about 200 phytoplankton species.[12] They belong either to the kingdom Protista, according to Robert Whittaker's Five kingdom classification, or clade Hacrobia, according to the newer biological classification system. Within the Hacrobia, the coccolithophores are in the phylum or division Haptophyta, class Prymnesiophyceae (or Coccolithophyceae).[5] Coccolithophores are distinguished by special calcium carbonate plates (or scales) of uncertain function called coccoliths, which are also important microfossils. However, there are Prymnesiophyceae species lacking coccoliths (e.g. in genus Prymnesium), so not every member of Prymnesiophyceae is a coccolithophore.[13]

Coccolithophores are single-celled phytoplankton that produce small calcium carbonate (CaCO3) scales (coccoliths) which cover the cell surface in the form of a spherical coating, called a coccosphere. They have been an integral part of marine plankton communities since the Jurassic.[14][15] Today, coccolithophores contribute ~1–10% to primary production in the surface ocean[16] and ~50% to pelagic CaCO3 sediments.[17] Their calcareous shell increases the sinking velocity of photosynthetically fixed CO2 into the deep ocean by ballasting organic matter.[18][19] At the same time, the biogenic precipitation of calcium carbonate during coccolith formation reduces the total alkalinity of seawater and releases CO2.[20][21] Thus, coccolithophores play an important role in the marine carbon cycle by influencing the efficiency of the biological carbon pump and the oceanic uptake of atmospheric CO2.[1]

As of 2021, it is not known why coccolithophores calcify and how their ability to produce coccoliths is associated with their ecological success.[22][23][24][25][26] The most plausible benefit of having a coccosphere seems to be a protection against predators or viruses.[27][25] Viral infection is an important cause of phytoplankton death in the oceans,[28] and it has recently been shown that calcification can influence the interaction between a coccolithophore and its virus.[29][30] The major predators of marine phytoplankton are microzooplankton like ciliates and dinoflagellates. These are estimated to consume about two-thirds of the primary production in the ocean[31] and microzooplankton can exert a strong grazing pressure on coccolithophore populations.[32] Although calcification does not prevent predation, it has been argued that the coccosphere reduces the grazing efficiency by making it more difficult for the predator to utilise the organic content of coccolithophores.[33] Heterotrophic protists are able to selectively choose prey on the basis of its size or shape and through chemical signals[34][35] and may thus favor other prey that is available and not protected by coccoliths.[1]

Coccolithophores are spherical cells about 5–100 micrometres across, enclosed by calcareous plates called coccoliths, which are about 2–25 micrometres across. Each cell contains two brown chloroplasts which surround the nucleus.[38]

Enclosed in each coccosphere is a single cell with membrane bound organelles. Two large chloroplasts with brown pigment are located on either side of the cell and surround the nucleus, mitochondria, golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum, and other organelles. Each cell also has two flagellar structures, which are involved not only in motility, but also in mitosis and formation of the cytoskeleton.[39] In some species, a functional or vestigial haptonema is also present.[40] This structure, which is unique to haptophytes, coils and uncoils in response to environmental stimuli. Although poorly understood, it has been proposed to be involved in prey capture.[39]

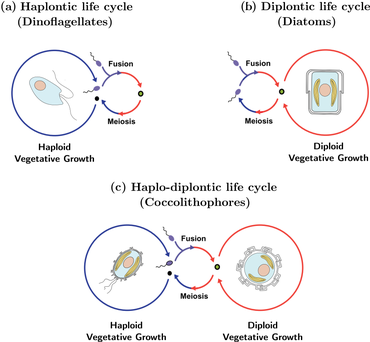

The life cycle of coccolithophores is complex and is characterized by an alternation of both asexual and sexual phases. The asexual phase is known as the haploid phase, while the sexual phase is known as the diploid phase. During the haploid phase, coccolithophores produce haploid cells through mitosis. These haploid cells can then divide further through mitosis or undergo sexual reproduction with other haploid cells. The resulting diploid cell goes through meiosis to produce haploid cells again, starting the cycle over. With coccolithophores, asexual reproduction by mitosis is possible in both phases of the life cycle, which is a contrast with most other organisms that have alternating life cycles.[42] Both abiotic and biotic factors may affect the frequency with which each phase occurs.[43]

Coccolithophores reproduce asexually through binary fission. In this process the coccoliths from the parent cell are divided between the two daughter cells. There have been suggestions stating the possible presence of a sexual reproduction process due to the diploid stages of the coccolithophores, but this process has never been observed.[44]

K or r- selected strategies of coccolithophores depend on their life cycle stage. When coccolithophores are diploid, they are r-selected. In this phase they tolerate a wider range of nutrient compositions. When they are haploid they are K- selected and are often more competitive in stable low nutrient environments.[44] Most coccolithophores are K strategist and are usually found on nutrient-poor surface waters. They are poor competitors when compared to other phytoplankton and thrive in habitats where other phytoplankton would not survive.[45] These two stages in the life cycle of coccolithophores occur seasonally, where more nutrition is available in warmer seasons and less is available in cooler seasons. This type of life cycle is known as a complex heteromorphic life cycle.[44]

Coccolithophores occur throughout the world's oceans. Their distribution varies vertically by stratified layers in the ocean and geographically by different temporal zones.[46] While most modern coccolithophores can be located in their associated stratified oligotrophic conditions, the most abundant areas of coccolithophores where there is the highest species diversity are located in subtropical zones with a temperate climate.[47] While water temperature and the amount of light intensity entering the water's surface are the more influential factors in determining where species are located, the ocean currents also can determine the location where certain species of coccolithophores are found.[48]

Although motility and colony formation vary according to the life cycle of different coccolithophore species, there is often alternation between a motile, haploid phase, and a non-motile diploid phase. In both phases, the organism's dispersal is largely due to ocean currents and circulation patterns.[49]

Within the Pacific Ocean, approximately 90 species have been identified with six separate zones relating to different Pacific currents that contain unique groupings of different species of coccolithophores.[50] The highest diversity of coccolithophores in the Pacific Ocean was in an area of the ocean considered the Central North Zone which is an area between 30 oN and 5 oN, composed of the North Equatorial Current and the Equatorial Countercurrent. These two currents move in opposite directions, east and west, allowing for a strong mixing of waters and allowing a large variety of species to populate the area.[50]

In the Atlantic Ocean, the most abundant species are E. huxleyi and Florisphaera profunda with smaller concentrations of the species Umbellosphaera irregularis, Umbellosphaera tenuis and different species of Gephyrocapsa.[50] Deep-dwelling coccolithophore species abundance is greatly affected by nutricline and thermocline depths. These coccolithophores increase in abundance when the nutricline and thermocline are deep and decrease when they are shallow.[51]

The complete distribution of coccolithophores is currently not known and some regions, such as the Indian Ocean, are not as well studied as other locations in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. It is also very hard to explain distributions due to multiple constantly changing factors involving the ocean's properties, such as coastal and equatorial upwelling, frontal systems, benthic environments, unique oceanic topography, and pockets of isolated high or low water temperatures.[53]

The upper photic zone is low in nutrient concentration, high in light intensity and penetration, and usually higher in temperature. The lower photic zone is high in nutrient concentration, low in light intensity and penetration and relatively cool. The middle photic zone is an area that contains the same values in between that of the lower and upper photic zones.[47]

The Great Calcite Belt of the Southern Ocean is a region of elevated summertime upper ocean calcite concentration derived from coccolithophores, despite the region being known for its diatom predominance. The overlap of two major phytoplankton groups, coccolithophores and diatoms, in the dynamic frontal systems characteristic of this region provides an ideal setting to study environmental influences on the distribution of different species within these taxonomic groups.[56]

The Great Calcite Belt, defined as an elevated particulate inorganic carbon (PIC) feature occurring alongside seasonally elevated chlorophyll a in austral spring and summer in the Southern Ocean,[57] plays an important role in climate fluctuations,[58][59] accounting for over 60% of the Southern Ocean area (30–60° S).[60] The region between 30° and 50° S has the highest uptake of anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO2) alongside the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans.[61]

Recent studies show that climate change has direct and indirect impacts on Coccolithophore distribution and productivity. They will inevitably be affected by the increasing temperatures and thermal stratification of the top layer of the ocean, since these are prime controls on their ecology, although it is not clear whether global warming would result in net increase or decrease of coccolithophores. As they are calcifying organisms, it has been suggested that ocean acidification due to increasing carbon dioxide could severely affect coccolithophores.[51] Recent CO2 increases have seen a sharp increase in the population of coccolithophores.[62]

Coccolithophores are one of the more abundant primary producers in the ocean. As such, they are a large contributor to the primary productivity of the tropical and subtropical oceans, however, exactly how much has yet to have been recorded.[66]

The ratio between the concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus and silicate in particular areas of the ocean dictates competitive dominance within phytoplankton communities. Each ratio essentially tips the odds in favor of either diatoms or other groups of phytoplankton, such as coccolithophores. A low silicate to nitrogen and phosphorus ratio allows coccolithophores to outcompete other phytoplankton species; however, when silicate to phosphorus to nitrogen ratios are high coccolithophores are outcompeted by diatoms. The increase in agricultural processes lead to eutrophication of waters and thus, coccolithophore blooms in these high nitrogen and phosphorus, low silicate environments.[4]

The calcite in calcium carbonate allows coccoliths to scatter more light than they absorb. This has two important consequences: 1) Surface waters become brighter, meaning they have a higher albedo, and 2) there is induced photoinhibition, meaning photosythetic production is diminished due to an excess of light. In case 1), a high concentration of coccoliths leads to a simultaneous increase in surface water temperature and decrease in the temperature of deeper waters. This results in more stratification in the water column and a decrease in the vertical mixing of nutrients. However, a 2012 study estimated that the overall effect of coccolithophores on the increase in radiative forcing of the ocean is less than that from anthropogenic factors.[67] Therefore, the overall result of large blooms of coccolithophores is a decrease in water column productivity, rather than a contribution to global warming.

Their predators include the common predators of all phytoplankton including small fish, zooplankton, and shellfish larvae.[45][68] Viruses specific to this species have been isolated from several locations worldwide and appear to play a major role in spring bloom dynamics.

No environmental evidence of coccolithophore toxicity has been reported, but they belong to the class Prymnesiophyceae which contain orders with toxic species. Toxic species have been found in the genera Prymnesium Massart and Chrysochromulina Lackey. Members of the genus Prymnesium have been found to produce haemolytic compounds, the agent responsible for toxicity. Some of these toxic species are responsible for large fish kills and can be accumulated in organisms such as shellfish; transferring it through the food chain. In laboratory tests for toxicity members of the oceanic coccolithophore genera Emiliania, Gephyrocapsa, Calcidiscus and Coccolithus were shown to be non-toxic as were species of the coastal genus Hymenomonas, however several species of Pleurochrysis and Jomonlithus, both coastal genera were toxic to Artemia.[68]

Coccolithophorids are predominantly found as single, free-floating haploid or diploid cells.[46]

Most phytoplankton need sunlight and nutrients from the ocean to survive, so they thrive in areas with large inputs of nutrient rich water upwelling from the lower levels of the ocean. Most coccolithophores require sunlight only for energy production, and have a higher ratio of nitrate uptake over ammonium uptake (nitrogen is required for growth and can be used directly from nitrate but not ammonium). Because of this they thrive in still, nutrient-poor environments where other phytoplankton are starving.[69] Trade-offs associated with these faster growth rates include a smaller cell radius and lower cell volume than other types of phytoplankton.

Giant DNA-containing viruses are known to lytically infect coccolithophores, particularly E. huxleyi. These viruses, known as E. huxleyi viruses (EhVs), appear to infect the coccosphere coated diploid phase of the life cycle almost exclusively. It has been proposed that as the haploid organism is not infected and therefore not affected by the virus, the co-evolutionary "arms race" between coccolithophores and these viruses does not follow the classic Red Queen evolutionary framework, but instead a "Cheshire Cat" ecological dynamic.[70] More recent work has suggested that viral synthesis of sphingolipids and induction of programmed cell death provides a more direct link to study a Red Queen-like coevolutionary arms race at least between the coccolithoviruses and diploid organism.[43]

Coccolithophores are members of the clade Haptophyta, which is a sister clade to Centrohelida, which are both in Haptista.[71] The oldest known coccolithophores are known from the Late Triassic, around the Norian-Rhaetian boundary.[72] Diversity steadily increased over the course of the Mesozoic, reaching its apex during the Late Cretaceous. However, there was a sharp drop during the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event, when more than 90% of coccolithophore species became extinct. Coccoliths reached another, lower apex of diversity during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum, but have subsequently declined since the Oligocene due to decreasing global temperatures, with species that produced large and heavily calcified coccoliths most heavily affected.[25]

Each coccolithophore encloses itself in a protective shell of coccoliths, calcified scales which make up its exoskeleton or coccosphere.[73] The coccoliths are created inside the coccolithophore cell and while some species maintain a single layer throughout life only producing new coccoliths as the cell grows, others continually produce and shed coccoliths.

The primary constituent of coccoliths is calcium carbonate, or chalk. Calcium carbonate is transparent, so the organisms' photosynthetic activity is not compromised by encapsulation in a coccosphere.[45]

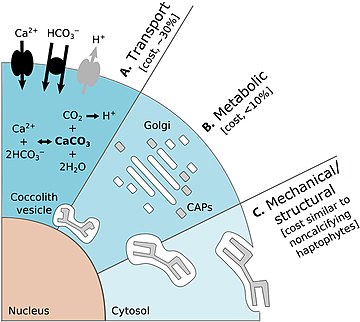

Coccoliths are produced by a biomineralization process known as coccolithogenesis.[38] Generally, calcification of coccoliths occurs in the presence of light, and these scales are produced much more during the exponential phase of growth than the stationary phase.[74] Although not yet entirely understood, the biomineralization process is tightly regulated by calcium signaling. Calcite formation begins in the golgi complex where protein templates nucleate the formation of CaCO3 crystals and complex acidic polysaccharides control the shape and growth of these crystals.[49] As each scale is produced, it is exported in a Golgi-derived vesicle and added to the inner surface of the coccosphere. This means that the most recently produced coccoliths may lie beneath older coccoliths.[42] Depending upon the phytoplankton's stage in the life cycle, two different types of coccoliths may be formed. Holococcoliths are produced only in the haploid phase, lack radial symmetry, and are composed of anywhere from hundreds to thousands of similar minute (ca 0.1 μm) rhombic calcite crystals. These crystals are thought to form at least partially outside the cell. Heterococcoliths occur only in the diploid phase, have radial symmetry, and are composed of relatively few complex crystal units (fewer than 100). Although they are rare, combination coccospheres, which contain both holococcoliths and heterococcoliths, have been observed in the plankton recording coccolithophore life cycle transitions. Finally, the coccospheres of some species are highly modified with various appendages made of specialized coccoliths.[53]

While the exact function of the coccosphere is unclear, many potential functions have been proposed. Most obviously coccoliths may protect the phytoplankton from predators. It also appears that it helps them to create a more stable pH. During photosynthesis carbon dioxide is removed from the water, making it more basic. Also calcification removes carbon dioxide, but chemistry behind it leads to the opposite pH reaction; it makes the water more acidic. The combination of photosynthesis and calcification therefore even out each other regarding pH changes.[75] In addition, these exoskeletons may confer an advantage in energy production, as coccolithogenesis seems highly coupled with photosynthesis. Organic precipitation of calcium carbonate from bicarbonate solution produces free carbon dioxide directly within the cellular body of the alga, this additional source of gas is then available to the Coccolithophore for photosynthesis. It has been suggested that they may provide a cell-wall like barrier to isolate intracellular chemistry from the marine environment.[76] More specific, defensive properties of coccoliths may include protection from osmotic changes, chemical or mechanical shock, and short-wavelength light.[40] It has also been proposed that the added weight of multiple layers of coccoliths allows the organism to sink to lower, more nutrient rich layers of the water and conversely, that coccoliths add buoyancy, stopping the cell from sinking to dangerous depths.[77] Coccolith appendages have also been proposed to serve several functions, such as inhibiting grazing by zooplankton.[53]

Coccoliths are the main component of the Chalk, a Late Cretaceous rock formation which outcrops widely in southern England and forms the White Cliffs of Dover, and of other similar rocks in many other parts of the world.[9] At the present day sedimented coccoliths are a major component of the calcareous oozes that cover up to 35% of the ocean floor and is kilometres thick in places.[49] Because of their abundance and wide geographic ranges, the coccoliths which make up the layers of this ooze and the chalky sediment formed as it is compacted serve as valuable microfossils.

Calcification, the biological production of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), is a key process in the marine carbon cycle. Coccolithophores are the major planktonic group responsible for pelagic CaCO3 production.[78][79] The diagram on the right shows the energetic costs of coccolithophore calcification:

The diagram on the left shows the benefits of coccolithophore calcification. (A) Accelerated photosynthesis includes CCM (1) and enhanced light uptake via scattering of scarce photons for deep-dwelling species (2). (B) Protection from photodamage includes sunshade protection from ultraviolet (UV) light and photosynthetic active radiation (PAR) (1) and energy dissipation under high-light conditions (2). (C) Armor protection includes protection against viral/bacterial infections (1) and grazing by selective (2) and nonselective (3) grazers.[25]

The degree by which calcification can adapt to ocean acidification is presently unknown. Cell physiological examinations found the essential H+ efflux (stemming from the use of HCO3− for intra-cellular calcification) to become more costly with ongoing ocean acidification as the electrochemical H+ inside-out gradient is reduced and passive proton outflow impeded.[80] Adapted cells would have to activate proton channels more frequently, adjust their membrane potential, and/or lower their internal pH.[81] Reduced intra-cellular pH would severely affect the entire cellular machinery and require other processes (e.g. photosynthesis) to co-adapt in order to keep H+ efflux alive.[82][83] The obligatory H+ efflux associated with calcification may therefore pose a fundamental constraint on adaptation which may potentially explain why "calcification crisis" were possible during long-lasting (thousands of years) CO2 perturbation events[84][85] even though evolutionary adaption to changing carbonate chemistry conditions is possible within one year.[84][85] Unraveling these fundamental constraints and the limits of adaptation should be a focus in future coccolithophore studies because knowing them is the key information required to understand to what extent the calcification response to carbonate chemistry perturbations can be compensated by evolution.[86]

Silicate- or cellulose-armored functional groups such as diatoms and dinoflagellates do not need to sustain the calcification-related H+ efflux. Thus, they probably do not need to adapt in order to keep costs for the production of structural elements low. On the contrary, dinoflagellates (except for calcifying species;[87] with generally inefficient CO2-fixing RuBisCO enzymes[88] may even profit from chemical changes since photosynthetic carbon fixation as their source of structural elements in the form of cellulose should be facilitated by the ocean acidification-associated CO2 fertilization.[89][90] Under the assumption that any form of shell/exoskeleton protects phytoplankton against predation[27] non-calcareous armors may be the preferable solution to realize protection in a future ocean.[86]

The diagram on the right is a representation of how the comparative energetic effort for armor construction in diatoms, dinoflagellates and coccolithophores appear to operate. The frustule (diatom shell) seems to be the most inexpensive armor under all circumstances because diatoms typically outcompete all other groups when silicate is available. The coccosphere is relatively inexpensive under sufficient [CO2], high [HCO3−], and low [H+] because the substrate is saturating and protons are easily released into seawater.[80] In contrast, the construction of thecal elements, which are organic (cellulose) plates that constitute the dinoflagellate shell, should rather be favored at high H+ concentrations because these usually coincide with high [CO2]. Under these conditions dinoflagellates could down-regulate the energy-consuming operation of carbon concentrating mechanisms to fuel the production of organic source material for their shell. Therefore, a shift in carbonate chemistry conditions toward high [CO2] may promote their competitiveness relative to coccolithophores. However, such a hypothetical gain in competitiveness due to altered carbonate chemistry conditions would not automatically lead to dinoflagellate dominance because a huge number of factors other than carbonate chemistry have an influence on species composition as well.[86]

Currently, the evidence supporting or refuting a protective function of the coccosphere against predation is limited. Some researchers found that overall microzooplankton predation rates were reduced during blooms of the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi,[91][92] while others found high microzooplankton grazing rates on natural coccolithophore communities.[93] In 2020, researchers found that in situ ingestion rates of microzooplankton on E. huxleyi did not differ significantly from those on similar sized non-calcifying phytoplankton.[94] In laboratory experiments the heterotrophic dinoflagellate Oxyrrhis marina preferred calcified over non-calcified cells of E. huxleyi, which was hypothesised to be due to size selective feeding behaviour, since calcified cells are larger than non-calcified E. huxleyi.[95] In 2015, Harvey et al. investigated predation by the dinoflagellate O. marina on different genotypes of non-calcifying E. huxleyi as well as calcified strains that differed in the degree of calcification.[96] They found that the ingestion rate of O. marina was dependent on the genotype of E. huxleyi that was offered, rather than on their degree of calcification. In the same study, however, the authors found that predators which preyed on non-calcifying genotypes grew faster than those fed with calcified cells.[96] In 2018, Strom et al. compared predation rates of the dinoflagellate Amphidinium longum on calcified relative to naked E. huxleyi prey and found no evidence that the coccosphere prevents ingestion by the grazer.[97] Instead, ingestion rates were dependent on the offered genotype of E. huxleyi.[97] Altogether, these two studies suggest that the genotype has a strong influence on ingestion by the microzooplankton species, but if and how calcification protects coccolithophores from microzooplankton predation could not be fully clarified.[1]

Coccolithophores have both long and short term effects on the carbon cycle. The production of coccoliths requires the uptake of dissolved inorganic carbon and calcium. Calcium carbonate and carbon dioxide are produced from calcium and bicarbonate by the following chemical reaction:[98]

Because coccolithophores are photosynthetic organisms, they are able to use some of the CO2 released in the calcification reaction for photosynthesis.[99]

However, the production of calcium carbonate drives surface alkalinity down, and in conditions of low alkalinity the CO2 is instead released back into the atmosphere.[100] As a result of this, researchers have postulated that large blooms of coccolithophores may contribute to global warming in the short term.[101] A more widely accepted idea, however, is that over the long term coccolithophores contribute to an overall decrease in atmospheric CO2 concentrations. During calcification two carbon atoms are taken up and one of them becomes trapped as calcium carbonate. This calcium carbonate sinks to the bottom of the ocean in the form of coccoliths and becomes part of sediment; thus, coccolithophores provide a sink for emitted carbon, mediating the effects of greenhouse gas emissions.[101]

Research also suggests that ocean acidification due to increasing concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere may affect the calcification machinery of coccolithophores. This may not only affect immediate events such as increases in population or coccolith production, but also may induce evolutionary adaptation of coccolithophore species over longer periods of time. For example, coccolithophores use H+ ion channels in to constantly pump H+ ions out of the cell during coccolith production. This allows them to avoid acidosis, as coccolith production would otherwise produce a toxic excess of H+ ions. When the function of these ion channels is disrupted, the coccolithophores stop the calcification process to avoid acidosis, thus forming a feedback loop.[102] Low ocean alkalinity, impairs ion channel function and therefore places evolutionary selective pressure on coccolithophores and makes them (and other ocean calcifiers) vulnerable to ocean acidification.[103] In 2008, field evidence indicating an increase in calcification of newly formed ocean sediments containing coccolithophores bolstered the first ever experimental data showing that an increase in ocean CO2 concentration results in an increase in calcification of these organisms. Decreasing coccolith mass is related to both the increasing concentrations of CO2 and decreasing concentrations of CO32− in the world's oceans. This lower calcification is assumed to put coccolithophores at ecological disadvantage. Some species like Calcidiscus leptoporus, however, are not affected in this way, while the most abundant coccolithophore species, E. huxleyi might be (study results are mixed).[102][104] Also, highly calcified coccolithophorids have been found in conditions of low CaCO3 saturation contrary to predictions.[3] Understanding the effects of increasing ocean acidification on coccolithophore species is absolutely essential to predicting the future chemical composition of the ocean, particularly its carbonate chemistry. Viable conservation and management measures will come from future research in this area. Groups like the European-based CALMARO[105] are monitoring the responses of coccolithophore populations to varying pH's and working to determine environmentally sound measures of control.

Gephyrocapsa oceanica (scale bar is 1 μm)

Coccolith fossils are prominent and valuable calcareous microfossils. They are the largest global source of biogenic calcium carbonate, and significantly contribute to the global carbon cycle.[106] They are the main constituent of chalk deposits such as the white cliffs of Dover.

Of particular interest are fossils dating back to the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum 55 million years ago. This period is thought to correspond most directly to the current levels of CO2 in the ocean.[107] Finally, field evidence of coccolithophore fossils in rock were used to show that the deep-sea fossil record bears a rock record bias similar to the one that is widely accepted to affect the land-based fossil record.[108]

The coccolithophorids help in regulating the temperature of the oceans. They thrive in warm seas and release dimethyl sulfide (DMS) into the air whose nuclei help to produce thicker clouds to block the sun.[109] When the oceans cool, the number of coccolithophorids decrease and the amount of clouds also decrease. When there are fewer clouds blocking the sun, the temperature also rises. This, therefore, maintains the balance and equilibrium of nature.[110][111]

Coccolithophore cells are covered with protective calcified (chalk) scales called coccoliths

Coccolithophore cells are covered with protective calcified (chalk) scales called coccoliths Coccolithophores, or coccolithophorids, are single-celled organisms which are part of the phytoplankton, the autotrophic (self-feeding) component of the plankton community. They form a group of about 200 species, and belong either to the kingdom Protista, according to Robert Whittaker's five-kingdom system, or clade Hacrobia, according to a newer biological classification system. Within the Hacrobia, the coccolithophores are in the phylum or division Haptophyta, class Prymnesiophyceae (or Coccolithophyceae). Coccolithophores are almost exclusively marine, are photosynthetic, and exist in large numbers throughout the sunlight zone of the ocean.

Coccolithophores are the most productive calcifying organisms on the planet, covering themselves with a calcium carbonate shell called a coccosphere. However, the reasons they calcify remains elusive. One key function may be that the coccosphere offers protection against microzooplankton predation, which is one of the main causes of phytoplankton death in the ocean.

Coccolithophores are ecologically important, and biogeochemically they play significant roles in the marine biological pump and the carbon cycle. They are of particular interest to those studying global climate change because, as ocean acidity increases, their coccoliths may become even more important as a carbon sink. Management strategies are being employed to prevent eutrophication-related coccolithophore blooms, as these blooms lead to a decrease in nutrient flow to lower levels of the ocean.

The most abundant species of coccolithophore, Emiliania huxleyi, belongs to the order Isochrysidales and family Noëlaerhabdaceae. It is found in temperate, subtropical, and tropical oceans. This makes E. huxleyi an important part of the planktonic base of a large proportion of marine food webs. It is also the fastest growing coccolithophore in laboratory cultures. It is studied for the extensive blooms it forms in nutrient depleted waters after the reformation of the summer thermocline. and for its production of molecules known as alkenones that are commonly used by earth scientists as a means to estimate past sea surface temperatures.

Kokolitoj estas la plej malgrandaj planto-fosilioj aŭ vegetalaj fosilioj, ĉar estas unuĉelaj estuloj. Temas pri skeleteroj de Ĥrizofitoj aŭ flavbrunaj algoj, kiuj vivis kaj vivas en maro. La plej grava konsistaĵo de la plaketoj estas Karbonato de kalcio. Lastatempe oni uzas elektronikajn mikroskopojn por la pristudo de tiuj fosilioj. La scienco kiu prizorgas tiun fakon estas la Paleobotaniko ene de la Paleontologio. Ekzemplo de kokolito tutmonde grava estas la specio Emiliania hŭleyi.

Pro ties mikroskopa malgrandeco kaj la tutmonda disvastiĝo de plej parto de tiuj grupoj, la kokolitoj (kalka nanoplanktono) estas gravegaj kiel montrofosilio por solvi demandojn pri Tavolografio. Ili ankaŭ estas interesaj indikiloj pri ŝanĝoj de temperaturo kaj saleco de oceanoj. Tiuj ŝanĝoj estas dedukteblaj per kvantaj analizoj de la enhavo de la kalka nanoplanktono.

Endre Dudich, "Ĉu vi konas la Teron? Ĉapitroj el la geologiaj sciencoj", Scienca Eldona Centro de UEA, Budapest, 1983.

Kokolitoj estas la plej malgrandaj planto-fosilioj aŭ vegetalaj fosilioj, ĉar estas unuĉelaj estuloj. Temas pri skeleteroj de Ĥrizofitoj aŭ flavbrunaj algoj, kiuj vivis kaj vivas en maro. La plej grava konsistaĵo de la plaketoj estas Karbonato de kalcio. Lastatempe oni uzas elektronikajn mikroskopojn por la pristudo de tiuj fosilioj. La scienco kiu prizorgas tiun fakon estas la Paleobotaniko ene de la Paleontologio. Ekzemplo de kokolito tutmonde grava estas la specio Emiliania hŭleyi.

Pro ties mikroskopa malgrandeco kaj la tutmonda disvastiĝo de plej parto de tiuj grupoj, la kokolitoj (kalka nanoplanktono) estas gravegaj kiel montrofosilio por solvi demandojn pri Tavolografio. Ili ankaŭ estas interesaj indikiloj pri ŝanĝoj de temperaturo kaj saleco de oceanoj. Tiuj ŝanĝoj estas dedukteblaj per kvantaj analizoj de la enhavo de la kalka nanoplanktono.

Los cocolitóforos o cocolitofóridos (Coccolithophoridae) son algas unicelulares, protistas fitoplanctónicos pertenecientes al subfilo Haptophyta.[3][4] Se distinguen por estar cubiertos de placas (o escamas) distintivas de carbonato de calcio denominadas cocolitos, que son microfósiles importantes. Los cocolitóforos son exclusivamente marinos y se presentan en gran número en la zona fótica del océano. Un ejemplo de cocolitóforo importante globalmente es la especie Emiliania huxleyi.

Debido a su tamaño microscópico y a la extensa distribución de muchos de sus grupos, los cocolitos (nanoplancton calcáreo) son muy importantes como fósiles traza para resolver cuestiones de estratigrafía. Constituyen indicadores sensibles a los cambios de temperatura y salinidad de los océanos. Estos cambios pueden determinarse mediante análisis cuantitativos de la composición del nanoplancton calcáreo.

Los cocolitóforos o cocolitofóridos (Coccolithophoridae) son algas unicelulares, protistas fitoplanctónicos pertenecientes al subfilo Haptophyta. Se distinguen por estar cubiertos de placas (o escamas) distintivas de carbonato de calcio denominadas cocolitos, que son microfósiles importantes. Los cocolitóforos son exclusivamente marinos y se presentan en gran número en la zona fótica del océano. Un ejemplo de cocolitóforo importante globalmente es la especie Emiliania huxleyi.

Debido a su tamaño microscópico y a la extensa distribución de muchos de sus grupos, los cocolitos (nanoplancton calcáreo) son muy importantes como fósiles traza para resolver cuestiones de estratigrafía. Constituyen indicadores sensibles a los cambios de temperatura y salinidad de los océanos. Estos cambios pueden determinarse mediante análisis cuantitativos de la composición del nanoplancton calcáreo.

Les Coccosphaerales ou Coccolithophorales (du grec κοκκος «pépin», λίθος «pierre», φορος «porter» ) sont un ordre d'algues unicellulaires microscopiques appartenant à la classe des Prymnesiophyceae au sein du groupe des Haptophytes. L'accumulation de leur squelette fossilisé est le composant majoritaire de la craie. Elles font partie des Coccolithophoridés.

Ce sont des organismes exclusivement marins, que l'on rencontre en milieu pélagique. Ces algues protègent leur unique cellule sous une couche de plaques de calcite généralement discoïdes appelées coccolithes.

La craie est constituée en majeure partie de coccolithophoridés qui ont sédimenté au fond d'une mer ou d'un océan, se sont fossilisés et ont pris en masse.

Après la mort des coccolithophoridés, les coccolithes qui sédimentent au fond de la mer vont constituer l'essentiel des énormes couches de craie qui caractérisent la période géologique du Crétacé. Lors de la crise biologique Crétacé-Tertiaire, 50 % des espèces de coccolithophoridés disparurent.

Selon AlgaeBase (17 août 2015)[2] :

Selon ITIS (17 août 2015)[3] :

Selon World Register of Marine Species (17 août 2015)[4] :

Selon NCBI (1 janvier 2015)[5] :

Les Coccosphaerales ou Coccolithophorales (du grec κοκκος «pépin», λίθος «pierre», φορος «porter» ) sont un ordre d'algues unicellulaires microscopiques appartenant à la classe des Prymnesiophyceae au sein du groupe des Haptophytes. L'accumulation de leur squelette fossilisé est le composant majoritaire de la craie. Elles font partie des Coccolithophoridés.

Un cocolitóforo (ou cocolitofórido[2]) é un tipo de algas unicelulares planctónicas eucariotas, que se distínguen polas placas de carbonato de calcio especiais que as cobren, de incerta función, chamadas cocólitos, que son tamén importantes microfósiles. Antes eran clasificados no antigo reino Protista e nas modernas clasificacións pertencen ao clado Hacrobia e ao filo ou división Haptophyta, e forman unha parte da clase Prymnesiophyceae (ou Coccolithophyceae).[3] Porén, hai especies de Prymnesiophyceae que carecen de cocólitos (por exemplo no xénero Prymnesium), polo que non todos os membros de Prymnesiophyceae son cocolitofóridos.[4] Os cocolitóforos son case exclusivamente mariños e encóntranse en grandes cantidades na zona fótica do océano.

A especie máis abundante de cocolitóforo é Emiliania huxleyi, que pertence á orde Isochrysidales e á familia Noëlaerhabdaceae.[3] Vive principalmente en océanos temperados, subtropicais e tropicais.[5] E. huxleyi constitúe unha parte importante do plancto de moitas cadeas tróficas mariñas. É tamén o cocolitóforo de crecemento máis rápido en cultivos de laboratorio.[6] Estúdase polas súas enormes floracións en augas escasas en nutrientes despois de que se volve formar a termoclina de verán,[7][8] e pola súa produción de alquenonas, que permiten estimar a temperatura superficial do mar no pasado.[9] Os cocolitóforos son de especial interese para estudar o cambio climático global, porque a medida que aumenta a acidificación do océano, os seus cocólitos poden ser de grande importancia como sumidoiros de carbono.[10] Ademais, estanse empregando diversas estratexias para impedir as floracións de cocolitóforos relacionadas coa eutrofización, xa que estas floracións conducen a unha diminución da fluxo de nutrientes en niveis inferiores do océano.[11]

Os cocolitóforos son células esféricas de 5 a 100 micrómetros de diámetro, encerradas nunha cuberta de placas calcarias chamadas cocólitos, cada unha das cales ten de 2 a 25 micrómetros de diámetro. Os cocólitos forman un exoesqueleto calcario, que recibe o nome de cocosfera, no que cada un destes organismos unicelulares está encerrado.[12] Os cocólitos fórmanse dentro da célula e aínda que algunhas especies manteñen unha soa capa de cocólitos durante toda a súa vida e só producen novos cocólitos a medida que crecen, outras prodúcenos continuamente e vanse desprendendo deles.[13]

O principal constituínte dos cocólitos é o carbonato de calcio. O carbonato de calcio forma unha capa transparente, polo que a actividade fotosintética do organismo non se ve comprometida pola encapsulación na cocosfera.[14]

Os cocólitos prodúcense por un proceso de biomineralización chamado cocolitoxénese.[13] Xeralmente, a calcificación dos cocólitos ocorre en presenza de luz e estas escamas calcarias fórmanse sobre todo durante a fase exponencial de crecemento e con menor intensidade na fase estacionaria.[15] Aínda que non se comprende totalmente, o proceso de mineralización está estreitamente regulado por sinalización por calcio. A formación de calcita empeza no complexo de Golgi, onde moldes proteicos nuclean a formación de cristais de CaCO3, e polisacáridos ácidos complexos controlan a forma e o crecemento deses cristais.[16] A medida que se forma unha destas escamas, é exportada nunha vesícula que deriva do complexo de Golgi e engadida á superficie interna da cocosfera. Isto significa que os cocólitos acabados de producir están debaixo dos cocólitos máis vellos.[17] Dependendo da fase do ciclo vital do fitoplancto, poden formarse dous tipos diferentes de cocólitos. Os holococólitos prodúcense só na fase haploide, carecen de simetría radial e están compostos de centos ou miles de cristais rómbicos de calcita diminutos (duns 0,1 µm) similares. Estes cristais crese que se forman polo menos parcialmente fóra da célula. Os heterococólitos fórmanse só na fase diploide, teñen simetría radial e están compostos de relativamente poucas unidades de cristais complexos (menos de 100). Aínda que son raras, tamén se observaron cocosferas combinadas, que conteñen tanto holococólitos coma heterococólitos, nos rexistros das transicións do ciclo vital dos cocolitóforos. Finalmente, as cocosferas dalgunhas especies están altamente modificadas con varios apéndices feitos con cocólitos especializados.[18]

Aínda que non se coñece con certeza cal é a función da cocosfera, propuxéronse para ela diversas posibles funcións. A máis obvia é que os cocólitos protexen o fitoplancto dos predadores. Ademais, estes exoesqueletos poden proporcionar unha vantaxe na produción de enerxía, xa que a cocolitoxénese parece estar altamente acoplada coa fotosíntese. A precipitación orgánica de carbonato de calcio a partir de bicarbonato en disolución produce dióxido de carbono libre directamente dentro da célula da alga; esta fonte adicional de gas queda dispoñible para utilizala na fotosíntese do cocolitóforo. Suxeriuse que pode proporcionar unha barreira similar a unha parede celular que ille a química intracelular do ambiente mariño exterior.[19] As propiedades protectoras dos cocólitos poden consistir en protexer contra os cambios osmóticos, shocks mecánicos ou químicos e a luz de lonxitude de onda curta.[20] Propúxose que o peso engadido das múltiples capas de cocólitos permite que o organismo se afunda a máis profundidade ata capas do mar máis ricas en nutrientes ou, inversamente, que os cocólitos proporcionan flotación, evitando que a célula se afunda a profundidades excesivas perigosas.[21] Tamén se propuxo que os apéndices dos cocólitos realizan diversas funcións, como impedir ser comido polo zooplancto.[18]

Os cocólitos son o principal compoñente da creta, unha rocha formada no Cretáceo tardío, como a que aflora nos famosos cantís brancos de Dover na costa inglesa do Canal da Mancha, e outras rochas similares en moitas partes do mundo.[8] Actualmente os cocólitos sedimentados son un compoñente principal dos sedimentos peláxicos calcarios que cobren un 35% do fondo oceánico e nalgúns lugares son de varios quilómetros de grosor.[16] Debido á súa abundancia e ampla distribución xeográfica, os cocolitos que forman capas deste tipo de sedimento e o sedimento calcario formado cando se compacta serve como valiosa fonte de microfósiles.

Dentro da cocosfera hai unha soa célula con diversos orgánulos membranosos. Ten dous grandes cloroplastos cun pigmento marrón que están localizados a cada lado da célula rodeando o núcleo, mitocondrias, complexo de Golgi, retículo endoplasmático e outros orgánulos. Cada célula ten dúas estruturas flaxelares, que non só interveñen na mobilidade, senón tamén na mitose e na formación do citoesqueleto.[22] Nalgunhas especies, hai tamén un haptonema vestixial ou funcional.[20] Esta estrutura, que é única das haptófitas, enrólase e desenrólase en resposta aos estímulos ambientais.[22]

O ciclo vital dos cocolitóforos caracterízase por unha alternancia de fases diploide e haploide. Pasan da fase haploide á diploide por singamia e da diploide á haploide por meiose. A diferenza da maioría dos organismos con ciclos vitais alternantes, a reprodución asexual por mitose é posible en ambas as fases do ciclo vital.[17] A frecuencia coa que ocorre cada fase depende tanto de factores abióticos coma bióticos.[23]

Os cocolitóforos reprodúcense asexualmente por fisión binaria. Neste proceso os cocólitos da célula parental son repartidos entre as células fillas. Aínda que se ten suxerido a posible presenza dun proceso de reprodución sexual debido á existencia de estadios diploides nos cocolitóforos, este proceso non foi nunca observado.[24] As estratexias do K ou do r dos cocolitóforos dependen da fase do seu ciclo vital. Cando os cocolitóforos son diploides, seguen a estratexia do r. Nesta fase toleran unha ampla variedade de composicións de nutrientes. Cando son haploides seguen a estratexia do K e adoitan ser máis competitivos en ambientes baixos en nutrientes estables.[24] A maioría dos cocolitóforos son estrategas do K e atópanse xeralmente en augas superficiais pobres en nutrientes. Son malos competidores se os comparamos con outro tipo de fitoplancto e prosperan en hábitats onde outro fitoplancto non podería sobrevivir.[14] Estas dúas fases do ciclo vital dos cocolitóforos ocorren estacionalmente, no que se dispón de máis nutrición en estacións máis cálidas e de menos nas máis frías. Este tipo de ciclo vital denomínase heteromórfico complexo.[24]

Os cocolitóforos viven practicamentre en todos os océanos do mundo. A súa distribución varía verticalmente en capas estratificadas do océano e xeograficamente en diferentes zonas temporais.[25] Aínda que a maioría dos cocolitóforos máis modernos poden ser localizados nas súas condicións oligotróficas estrtificadas asociadas, as áreas máis abundantes de cocolitóforos onde hai a maior diversidade de especies están localizadas nas zonas subtropicais cun clima temperado.[26] Aínda que a temperatura da auga e a cantidade de intensidade de luz que entra na superficie da auga son os factores que máis inflúen para determinar onde se localizan as especies, as correntes oceánicas tamén poden determinar a localización onde se encontrarán certas especies de cocolitóforos.[27]

Aínda que a motilidade e a formación de colonias varía de acordo co ciclo vital de diferentes especies de cocolitóforos, hai a miúdo alternancia entre unha fase móbil haploide e outra inmóbil diploide. En ambas as fases, a dispersión do organismo débese en gran medida aos padróns de correntes e circulación oceánica.[16]

No océano Pacífico identificáronse aproximadamente 90 especies con seis zonas separadas en relación con diferentes correntes dese océano que conteñen agrupacións únicas de especies de cocolitóforos.[28] A maior diversidade de cocolitóforos no océano Pacífico atopouse na área denominada Zona Norte Central, que é unha área entre 30 oN e 5 oN, composta da corrente ecuatorial norte e a contracorrente ecuatorial. Estas dúas correntes móvense en direccións opostas, cara ao leste e ao oeste, permitindo unha forte mestura das augas e que unha ampla variedade de especies poboe a área.[28]

No océano Atlántico as especies máis abondosas son Emiliania huxleyi e Florisphaera profunda con menores concentracións de Umbellosphaera irregularis, Umbellosphaera tenuis e diferentes especies de Gephyrocapsa.[28] A abundancia dos cocolitóferos que viven en zonas profundas está moi afectada polas profundidades da nutriclina e a termoclina. Estes cocolitóforos incrementan a súa abundancia cando a nutriclina e a termoclina están profundas e diminúen cando están máis superficiais.[29]

A distribución completa mundial de cocolitóforos actualmente non se coñece e nalgunhas rexións, como o océano Índico, non se coñece tan ben coma noutras localizacións nos océanos Pacífico e Atlántico. É difícil explicar as distribucións debido a múltiples factores que cambian constantemente e implican as propiedades do océano, como os afloramentos costeiro e ecuatorial, sistemas frontais, ambientes bentónicos, topografía oceánica peculiar e bolsas illadas de auga de temperatura alta ou baixa.[18]

A zona fótica superior ten unha baixa concentración de nutrientes, unhas elevadas intensidade e penetración da luz e xeralmente unha maior temperatura. A zona fótica inferior ten unha elevada concentración de nutrientes e unhas baixas intensidade e penetración da luz e é relativamente fría. A zona fótica media é unha área que contén valores intermedios entre os das zonas fóticas superior e inferior.[26]

Recentes estudos mostraron que o cambio climático ten impactos directos e indirectos sobre a distribución de cocolitóforos e a produtividade. Estará inevitablemente afectada polo incremento de temperaturas e a estratificación termal da capa superior do océano, xa que estes son os controis primarios na súa ecoloxía, aínda que non está claro se o quecemento global terá como resultado un incremento ou decremento neto de cocolitóforos. Suxeiruse que como teñen que calcificarse, a acidificación do océano debida ao incremento do dióxido de carbono podería afectar gravemente os cocolitóforos.[29] Os aumentos recentes de CO2 foron acompalados dun brusco aumento da poboación de cocolitóforos.[30]

Os cocolitóforos son un dos produtores primarios máis abundantes do océano e son uns grandes contribuíntes á produtividade primaria dos océanos tropicais e subtropicais, pero non se sabe exactamente canto.[31]

A proporción entre as concentracións de nitróxeno, fósforo e silicato en determinadas áreas do océano determina a dominancia competitiva entre as comunidades de fitoplancto. Cada proporción esencialmente favorece ou ás diatomeas ou a outros grupos de fitoplancto, como os cocolitóforos. Unha proporción baixa de silicato respecto a nitróxeno e fóforo permite que os cocolitóforos superen na competición a outras especies de fitoplancto; porén, cando esta proporción é alta os cocolitóforos son superados polas diatomeas. O incremento dos procesos agrícolas (exceso de fertilizantes) conduce á eutrofización das augas e ás floracións de cocolitóforos nestes ambientes altos en nitróxeno e fósforo e baixos en silicato.[11]

A calcita dos cocólitos de carbonato de calcio dispersa máis luz da que absorbe. Isto ten dúas importantes consecuencias: 1) As augas superficiais fanse máis brillantes, o que significa que teñen maior albedo, e 2) hai unha fotoinhibición indiucida, o que significa que as augas máis profundas se fan máis escuras. Por tanto, unha alta concentración de cocólitos leva a un incremento simultáneo na temperatura da supericie das augas e unha diminución da temperatura das augas profundas. Isto ten como resultado máis estratificación na colmna de auga e unha diminución na mestura vertical de nutrientes. Porén, un estudo recente estimou que o efecto global dos cocolitóforos sobre o incremento no forzamento radiativo do océano é menor que os factores antropoxénicos.[32] Xa que logo, o resultado global das grandes floracions de cocolitóforos é unha diminución da produtividade da columna de auga, en vez dunha contribución ao quecemento global.

Entre os seus predadores están os predadores comúns de todo o fitoplancto como pequenos peixes, zooplancto e larvas de crustáceos e moluscos.[14][33] Illáronse virus específicos destas especies en varias localidades de todo o mundo e parecen desempeñar un papel importante na dinámica das floracións.

Non se informou de ningunha evidencia ambiental de toxicidade dos cocolitóforos, pero pertencen á clase Prymnesiophyceae que contén ordes con especies tóxicas. As especies tóxicas atópanse nos xéneros Prymnesium e Chrysochromulina. Algúns membros do xénero Prymnesium producen compostos hemolíticos, que son os axentes responsables da súa toxicidade. Algunhas destas especies tóxicas son responsables de grandes mortaldades de peixes e poden acumularse en organismos como moluscos ou crustáceos; transferíndose ao longo da cadea trófica. En probas de laboratorio para xéneros de cocolitóforos oceánicos con membros tóxicos, demostrouse que Emiliania, Gephyrocapsa, Calcidiscus e Coccolithus non son tóxicos, como tampouco as especies costeiras do xénero Hymenomonas; porén, varias especies de Pleurochrysis e Jomonlithus, ambos xéneros costeiros, eran tóxicas para o crustáceo Artemia.[33]

Os cocolitofóridos encóntranse predominantemente como células separadas que flotan libremente haploides ou diploides.[25]

A maioría do fitoplancto necesita luz solar e nutrientes do océano para sobrevivir, polo que prosperan en áreas con afloramentos de augas ricas en nutrientes que ascenden desde os niveis inferiores do océano. A maioría dos cocolitóforos só necesitan luz para a produción de enerxía e teñen unha maior proporción de captación de nitrato que de amonio (o nitróxeno cómpre para o crecemento e pode usarse directamente a partir do nitrato pero non do amonio). Debido a isto, prosperan en ambientes pobres en nutrientes, onde outro tipo de fitoplancto non se pode alimentar.[34] Compensacións asociadas con estas taxas de crecemento máis rápidas inclúen un menor raio e volume celular que outros tipos de fitoplancto.

Sábese que virus de ADN xigantes infectan liticamente a cocolitóforos, especialmente a Emiliania huxleyi. Estes virus, chamados virus de E. huxleyi (EhVs), parecen infectar case exclusivamente á fase diploide cuberta con cocosfera do ciclo vital. Propúxose que como o organismo haploide non está infectado e, por tanto, non afectado polo virus, a “carreira de armamentos evolutiva” entre os cocolitóforos e estes virus non segue o esquema evolutivo clásico da hipótese da Raíña Vermella, senón a chamada dinámica ecolóxica do “Gato de Cheshire”.[35] Traballos máis recentes suxeriron que a síntese viral de esfingolípidos e a indución da morte celular programada proporciona unha ligazón máis directa para estudar a carreira de armamentos coevolutiva tipo Raíña Vermella polo menos entre os cocolitovirus e o organismo diploide.[23]

Os cocolitóforos teñen efectos a longo e curto prazo sobre o ciclo do carbono. Para a produción de cocólitos cómpre a captación de carbono e calcio inorgánicos disoltos. O carbonato de calcio e o dióxido de carbono prodúcense a partir de calcio e bicarbonato pola seguinte reacción química: