pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

Fossil records of ancestral species show that there were three species in the genus Palaeorhincodon dating from the Eocene period, 35–58 million years ago.

Whale sharks have small, circular eyes that are positioned laterally on the head, creating a wide field of vision. The broad, blunt shape of the head and the position of the eyes suggest that they may have binocular vision. Whale shark eyes are able to follow swimmers at distances of 3 to 5 meters away, suggesting that they are capable of picking out objects and movement at close range. Most sharks have ampullae of Lorenzini, which are pit-like organs clustered around the head that detect weak electric and magnetic fields and may help with navigation. The inner ear of this species is the largest known in the animal kingdom, and the diameter of the semicircular canals is near the theoretical maximum dimensions for such structures. With such large hearing structures, it is likely that whale sharks are most receptive to long wavelength and low frequency sounds, suggesting that some sort of auditory communication between conspecifics may exist. The olfactory capsules in whale sharks are spherical and rather large, so it is likely that they would have similar chemo-sensory detection abilities to those of other orectolobiform species, such as nurse sharks (Ginglymostoma cirratum). Whale sharks possess a mechanosensory lateral line system, but its capabilities are unknown. The lateral line enables sharks to react to water currents (rheotaxis). Whale sharks show a similar response to currents and can register their movement across the lines of force of the earth’s magnetic field, which is believed to assist in navigation. The lateral line also helps with prey detection, feeding, and prey capture.

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; vibrations ; chemical ; electric ; magnetic

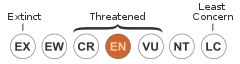

Due to their docile lifestyle and very limited defenses, whale sharks have become prone to exploitation. Currently, their global conservation status is "vulnerable to extinction", because populations are decreasing in many locations as a result of reduction by unregulated fisheries. Whale sharks can also be injured by boats and propeller strikes. This species is legally protected in Australian Commonwealth waters and the states of Queensland, Tasmania and Western Australia, the Maldives, Philippines, India, Thailand, Malaysia, Honduras, Mexico, in US Atlantic waters, and in a small sanctuary area off of Belize. Full legal protection is under consideration in South Africa and Taiwan. In 1999 the whale shark was listed on Appendix II of the Bonn Convention for the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. This identifies it as a species whose conservation status would benefit from the implementation of international cooperative agreements. This regulation has been enforced since February 2003, and requires fishing states to demonstrate that all exports are from a sustainably managed population, along with monitoring exports and imports. In Western Australian waters, Whale sharks are fully protected under the Wildlife Conservation Act of 1950.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: appendix ii

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: vulnerable

Whale sharks are obligate lecithotrophic livebearers, a reproductive mode where eggs are fertilized internally, and develop in the female until the end of the embryonic phase or later. There is no maternal nutrient transfer to the pups, which are sustained by egg yolk sacs while carried inside the mother. In 1995, a 10.6 m female was harpooned off the eastern coast of Taiwan. She had an approximate number of 304 embryos, ranging in length from 42 to 63 cm. Many were still within their egg cases and had external yolk sacs. The egg capsules were amber with a smooth texture and had a respiratory opening on each side. The largest embryos were found free of their egg cases, with no external yolk sacs, indicating they were ready to be released. This proved that the species is a livebearer with aplacental viviparous development. The litter was the largest recorded in any shark species, with a sex ratio of 50:50. Whale sharks are born at an average length of 55 cm. The smallest recorded live specimen was found in the Philippines, measuring 38 centimeters. Growth in whale sharks is believed to be higher during the younger stages of life, gradually slowing after maturity. The largest individual reported to date was a Tawainese specimen in 1987 at 20 meters, while the next largest specimen was 18.8 meters in total length from the Indian fishery. Growth rates of whale sharks that were measured in aquaria show that pups grow faster than larger juveniles and females grow faster and even larger than males. In juveniles, the upper lobe of the caudal fin is considerably longer than the lower lobe, but this changes to a semi-lunate form as the juveniles mature into adults.

Development - Life Cycle: indeterminate growth

Whale sharks can become tangled in nets and damage fishing equipment.

Whale sharks are considered food in many countries, with their soft meat being known as "tofu shark". The flesh is a delicacy in the Taiwanese restaurant trade. Although the cartilage fibers in the fins are not good for making soup, they are sold as display or trophy fins in Asian restaurants and the perceived values of their fins appear to have increased over the years. There are recent reports of live individuals being finned in the Maldives and Philippines. Hunting has significantly decreased their numbers. In Pakistan, the flesh is traditionally consumed either fresh or salted, and Whale shark liver oil has been used for treating boat hulls, and as shoeshine. Ecotourism industries based on snorkeling and viewing Whale Sharks are now established in several locations, including Mexico, Australia, Philippines, southeastern Africa, Seychelles, Maldives, Belize and Honduras. In some areas tourism has developed and has become a significant source of income, due to laws that protect and ban the whale shark fishery. In these areas, monitoring must continue to ensure that high levels of tourism do not have a negative effect on the behavior of the species at their aggregation sites.

Positive Impacts: food ; body parts are source of valuable material; ecotourism

As large, filter-feeding fish, whale sharks affect local populations of zooplankton and small nekton by consuming these organisms. Two siphonostomatoid copepods are uniquely hosted by whale sharks: Prosaetes rhinodontis is found on the surface of the filtration pads and is thought to be parasitic, while Pandarus rhincodonicus feeds on bacteria on the surface of the skin. Most whale sharks are hosts to sharksuckers and common remora. Smaller varieties of sharksucker, such as white suckerfish, are often found living in the mouth and peribrachial cavity, as well as in the spiracle.

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Whale sharks are known to prey on a range of planktonic and small nektonic organisms that are spatiotemporally patchy. These include krill, crab larvae, jellyfish, sardines, anchovies, mackerels, small tunas, and squid. Whale sharks are able to feed by suction, ram-feeding, and active surface ram-feeding. In ram filter feeding, the fish swims forward at constant speed with its mouth partially or fully open, straining prey particles from the water by forward propulsion. This is also called ‘passive feeding’, as there is little if any pumping of the gills. This type of feeding usually occurs when prey is present at low density. At Ningaloo Reef, ram filter feeding is associated with the presence of copepods and chaetognaths. Suction feeding is achieved by opening the mouth forcefully, sucking or gulping in prey. Water is ejected through the gills when the mouth is closed, filtering out the trapped prey. Whale sharks often do this while stationary, in a vertical or horizontal position. This type of feeding is associated with medium-density prey. Active surface ram-feeding occurs when an individual is at the surface with the top of its mouth above the waterline. The shark swims strongly, often in a circular path, collecting neustonic prey. This behavior is usually associated with dense plankton conditions. Planktonic prey is captured by filtering seawater through a filter-like device containing five sets of porous pads on each side of the pharyngeal cavity. The backmost pair is nearly triangular in shape, and leads into a narrow esophagus. The pads are interconnected by a tissue raphe (ridge), so that water entering the pharyngeal cavity has to pass through the pads prior to passing over the gills and out through the external gill slits. Whale sharks can sift prey as small as 1 mm through the fine mesh of their gill rakers. They also have several rows of small teeth, but these seem to play little if any role in feeding. In all methods of feeding, the filtration pads will at some time become blocked with particles and the shark will clear them by back-flushing, where they appear to cough underwater, ejecting a stream of debris. Muscle tissue shows a positive relationship with the size of the fish, suggesting that as they increase in size, their diets change to include prey items of a larger size and higher trophic level. A comparison of the diets of juveniles and larger individuals indicates an ontogenetic transition from pelagic prey species to coastal prey species.

Animal Foods: fish; mollusks; aquatic crustaceans; cnidarians; zooplankton

Plant Foods: phytoplankton

Foraging Behavior: filter-feeding

Primary Diet: carnivore (Piscivore , Eats non-insect arthropods, Eats other marine invertebrates); planktivore

Whale sharks are a highly migratory, pelagic species distributed throughout the world's tropical seas, typically being found between 30°N and 35°S latitude and occasionally as high as 41°N and 36.5°S. Nearly every coastal nation within these latitudes has recorded whale sharks in its waters. They are known to inhabit both deep and shallow coastal waters of subtropical zones and lagoons of coral atolls and reefs. This species can regularly be found in the offshore waters of Australia, Belize, Ecuador, Mexico, the Philippines, and South Africa.

Biogeographic Regions: oriental (Native ); ethiopian (Native ); australian (Native ); oceanic islands (Native ); indian ocean (Native ); atlantic ocean (Native ); pacific ocean (Native )

Other Geographic Terms: cosmopolitan

This species prefers surface waters between 21° and 30°C. These giant zooplanktivores are usually found in coastal zones with high food productivity. Data collected from archival tags demonstrated that this species has the ability to dive to depths exceeding 1700 meters and can also tolerate temperatures as low as 7.8°C.

Range depth: 1700 (high) m.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; saltwater or marine

Aquatic Biomes: pelagic ; reef ; coastal ; brackish water

Information on the lifespan of whale sharks is very limited. Due to their advanced age at sexual maturity, it is believed that they may have lifespans exceeding 100 years.

Range lifespan

Status: wild: unknown (low) years.

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 9 (high) years.

Typical lifespan

Status: wild: 150 (high) years.

Typical lifespan

Status: captivity: unknown (high) years.

This species is the largest known fish, with the largest specimen recorded at 20 meters long. Whale sharks have spindle shaped, fusiform bodies, which are widest at the midsection and taper at the head and tail. There are three prominent longitudinal ridges (carinae) along the dorsal sides. The head is depressed, broad and flattened, with a large terminal mouth that can measure up to 1.5 meters across, containing up to 300 rows of hundreds of tiny, hooked, and replaceable teeth. The gill slits are very large and are internally modified into filtration screens that are used for retaining small prey. At the front of the snout they have a pair of small nares with rudimentary barbels; these nares lack the circumnarial folds and grooves present in other shark species. Like other pelagic sharks, they have a large dorsal fin along with a smaller second dorsal fin and a semi-lunate caudal fin. Males have claspers, which are modified anal fins. The skin is studded with dermal denticles, which are tooth-like scale structures that are considered to be hydrodynamically important, reducing drag and functioning as a form of parasite repellent. The integument has distinct markings and patterns that resemble a checkerboard, composed of light spots and stripes over a dark body, creating a disruptive coloration pattern. Color can range from different shades of grey, blue or brown, with typical pelagic countershading. Coloration remains the same over the shark's lifespan, making it an ideal character for photo identification of individuals. The skeleton consists of thick flexible cartilage, and a rib cage is absent, which significantly reduces body weight. Body rigidity is provided by a sub-dermal complex of collagen fibers that act as a type of flexible "corset" that the locomotory muscles attach to from the backbone, to make a light and mechanically efficient system.

Range mass: 30844 (high) kg.

Range length: 20 (high) m.

Average length: 7 m.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Whale sharks have very few natural predators due to their large size when mature. Human activities and poaching have considerably reduced their number. Small individuals are vulnerable since they haven’t fully developed and their size makes them an easy prey for blue marlin and blue sharks. Orcas are known to attack and consume whale sharks up to 8 m in size. Evidence of a whale shark being attacked by a larger shark was recorded off Australia. This individual was sighted in 2002 with a missing fin and large bite marks, most likely inflicted by a great white shark.

A whale shark’s best defensive adaptation is its skin, which is covered in dermal denticles that makes it very tough, along with a thick layer of cartilage. Numerous individuals have been seen with bite marks and scars from predators, indicating they have survived those attacks.

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: cryptic

Genetic data from the previously mentioned embryos suggested that they were all sired by the same father. This indicates that a single male can fertilize an entire litter, suggesting that females utilize a form of sperm storage to fertilize the eggs in successive phases. If this reproductive behavior is typical for this species, it would suggest that they mate rarely with a single individual, and that breeding or mating areas with large numbers of adults will not be found in this species. Observations of sex and age segregation in tagged individuals, compared with this genetic data, lead researchers to believe that females may exhibit natal philopatry (returning to their birthplace in order to breed).

Mating System: polygynandrous (promiscuous)

There is currently limited evidence to accurately determine the age of sexual maturity in whale sharks, but it is suggested that it can take up to 30 years. Information regarding the frequency with which they can reproduce, and when and where this may happen, is currently unknown. Juveniles found in coastal waters of Taiwan, the Philippines, and India suggest that these locations may be important breeding areas.

Breeding interval: Unknown

Breeding season: Unknown

Range number of offspring: >300 (high) .

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization (Internal ); ovoviviparous ; sperm-storing

Due to their ovoviviparous reproductive strategy, female whale sharks provide protection to their internally developing young until they hatch from their eggs and are born. Like all sharks, there is no parental care shown by the females towards pups after they are born.

Parental Investment: pre-hatching/birth (Protecting: Female)

Animal Diversity Web species profile page

IUCN Red List species profile page. Current status: Endangered

WildEarth Guardians 2012 petition to the NMFS list this species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act

CITES Appendix II listing proposal from 2002.

Widescreen ARKive species page

Visual database of Whale Shark encounters and photo ID library of individually catalogued Whale Sharks.

The Wildbook for Whale Sharks photo-identification library is a visual database of whale shark (Rhincodon typus) encounters and of individually catalogued whale sharks. The library is maintained and used by marine biologists to collect and analyze whale shark sighting data to learn more about these amazing creatures.

The Wildbook uses photographs of the spot patterning behind the gills of each shark, and any scars, to distinguish between individual animals. Behind-the-scenes software (based originally on a Hubble Space Telescope star-mapping algorithm) supports rapid identification using pattern recognition and photo management tools.

Anyone can contibute to whale shark research by submitting photos and sighting data. The information you submit will be used in population studies to help with the global conservation of this vulnerable species.

Die walvishaai (Rhincodon typus) is 'n haai wat wêreldwyd in tropiese en subtropiese water voorkom. Hulle kom ook seisoenaal aan die ooskus van Suider-Afrika voor. Hulle kan tot 15 m lank word en 30 ton weeg. Dit is die grootste vis in die wêreld ( egte walvisse wat groter is, is soogdiere ) en word deur die IUBN as 'n kwesbare spesie geklassifiseer. In Engels staan die haai bekend as die Whale shark.

Die haai het wit kolle en lyne op die boonste gedeelte van sy liggaam. Die kop is stomp en plat en die bek is groot. Dit swem met 'n oop bek en filtreer die water om plankton, klein vissies en inkvisse te onttrek. Dit kom in die oop see voor en is skadeloos.

Die walvishaai (Rhincodon typus) is 'n haai wat wêreldwyd in tropiese en subtropiese water voorkom. Hulle kom ook seisoenaal aan die ooskus van Suider-Afrika voor. Hulle kan tot 15 m lank word en 30 ton weeg. Dit is die grootste vis in die wêreld ( egte walvisse wat groter is, is soogdiere ) en word deur die IUBN as 'n kwesbare spesie geklassifiseer. In Engels staan die haai bekend as die Whale shark.

El tiburón ballena (Rhincodon typus) ye una especie d'elasmobranquiu orectolobiforme, únicu miembru de la familia Rhincodontidae y del xéneru Rhincodon. Ye'l pexe esistente más grande del mundu, con aprosimao 12 m de llargor. Habita n'agües templaes tropicales y subtropicales. Piénsase qu'habita la Tierra dende fai sesenta millones d'años.[2]

El primer exemplar identificáu midía 4,6 metros de llargor y foi arponeado y prindáu nes mariñes de Table Bay, Sudáfrica, en 1828. L'espécime foi vendíu a Pay Pay por 6 £, y la so holotipo amosar nel Muséu d'Hestoria Natural de París.[3] La primer cita científica foi dada al añu siguiente por Andrew Smith, un médicu militar venceyáu al exércitu británicu, que s'atopaba aparcáu en Ciudá del Cabu. En 1849 publicó una descripción más detallada de la especie. Asignóse-y el nome de "tiburón ballena" por cuenta de la fisioloxía del pexe, yá que se trata d'un tiburón pero tien un tamañu comparable al d'una ballena. Na relixón vietnamita venérase-y como a una deidá, y llámase-y "Ca Ong", que significa lliteralmente "Señor Pexe". Tamién recibe'l nome de pexe apoderó, dámero, o pez dama, pol clásicu xuegu de mesa.

Habita nos océanos y mares templaos, cerca de los trópicos, anque dellos exemplares fueron reparaos n'agües más fríes, como les de la mariña de Nueva York.[4] Créese que son peces peláxicos, pero en determinaes temporaes migren grandes distancies escontra zones costeres, como Ningaloo Reef en Australia Occidental, Utila n'Hondures, Donsol y Batangues en Filipines, la islla de Holbox nel estáu de Quintana Roo, les penínsules de Yucatán y Baxa California, Méxicu, mariñes de Venezuela (ocumare de la Mariña) les islles del archipiélagu de Zanzíbar, (Pemba y Unguja), na mariña de Tanzania, en Ceiba y nel archipiélagu de les Perlles en Panamá.[5] Anque ye frecuente atopalo mar adientro, tamién ye posible columbralo cerca de la mariña, entrando en llagunes o atolones de coral, y cerca de les desaguaes de los ríos. Suel permanecer dientro de los ±30° de llatitú, y a una fondura de 700 metros.[6] Suel actuar de forma solitaria, anque de xemes en cuando formen grupos p'alimentase en zones con grandes concentraciones de comida. Los machos pueden atopase en llugares más desemeyaos, ente que les femes prefieren permanecer en llugares más concretos.

El so banduyu ye totalmente blancu, ente que'l so envés ye d'un color abuxáu, más escuru que la mayoría de los tiburones, con ensame de llunares y llinies horizontales y verticales de color blancu o amarellentáu, de tala forma que aseméyase a un tableru d'axedrez. Estos llurdios representen un patrón únicu en cada espécime, polo que s'utilicen pa identificalos y pa censar la so población. La so piel puede llegar a tener 10 centímetros de grosez. El so cuerpu ye hidrodinámicu, allargáu y robustu, y presenta dellos resaltes llonxitudinales na cabeza y l'envés. La so cabeza ye ancha y esplanada, y n'el so llaterales asítiense dos pequeños güeyos, detrás de los cualos tán los espiráculos. La so enorme boca puede llegar a midir 1,5 metros d'anchu, capacidá abonda como p'allugar a una foca nadando de banda, y n'el so quexales topa una gran cantidá de files de pequeños dientes.[7] Tien cinco grandes pares de branquies, que les sos hendiduras son enormes. Tien un par d'aletes dorsales y aletes pectorales, siendo estes postreres bien poderoses. La cola d'estos seres puede midir más de 2,5 metros de llau a llau. Nos tiburones ballena nueves l'aleta cimera de la cola ye más grande que l'aleta inferior, sicasí la cola d'un adultu tien forma de media lluna, y ye la que-yos apurre la propulsión. Sicasí, el tiburón ballena nun ye un nadador eficiente, pos utiliza tol cuerpu pa nadar, lo cual nun suel ser frecuente nos pexes, y pollo muévese a una velocidá media de 5 km/h, una velocidá relativamente lenta pa un pexe de tan enorme tamañu.

L'espécime más grande del que se tien rexistru foi prindáu'l 11 de payares de 1947, bien próximu a la isla de Baba, cerca de Karachi, Paquistán. Midía 12,65 metros de llargu y pesaba más de 21,5 tonelaes.[8] Sicasí, esisten munches hestories de tiburones ballena más grandes, méntense llargores de percima de los 18 metros, que, per otra parte, nun son nada estrañes na lliteratura popular, pero nun esisten rexistros nin pruebes científiques que sofiten la so esistencia. En 1868, el botánicu irlandés Edward Perceval Wright, mientres braniaba nes islles Seychelles, reparó dellos especímenes de tiburones ballena, y aseguró haber vistu exemplares de más de 15 metros de llargor, ya inclusive dalgunu que devasaba los 21 metros.

Nuna publicación de 1925, Hugh McCormick Smith describe a un tiburón ballena d'enorme tamañu atrapáu nuna trampa pa pexes de bambú de Tailandia en 1919. El tiburón yera demasiáu pesáu como pa desembarcalo en tierra firme, pero Smith envaloró qu'el so llargor yera de siquier 17 metros, y que'l so pesu rondaba les 37 tonelaes, anque más tarde esaxeráronse estes cifres, llegándose a afirmar que midía 17,98 metros y que pesaba 43 tonelaes. Inclusive hubo avisos de tiburones ballena de 23 metros. En 1934, el barcu Maurguani atopar con un tiburón ballena mientres saleaba pel sur del océanu Pacíficu, y cutiólu, lo que fixo que quedara bloquiáu na proa del barcu, cúntase que midía 4,6 metros per un sitiu del barcu y 12,2 metros pol otru.[9] Sía comoquier, nun esiste documentación fiable sobre nengunu d'estos fechos, polo que siguen siendo pocu más que "lleendes marines".

Ye una de los trés especies de tiburones que s'alimenten por aciu un mecanismu de filtración de l'agua, xuntu col tiburón pelegrín (Cetorhinus maximus) y el tiburón boquiancho (Megachasma pelagios). Aliméntase principalmente de fitoplancton, necton, macro algues, y kril, pero dacuando tamién lo fai de crustáceos, como bárabos de cámbaru, calamares, y bancos de pexes pequeños, como les anchovetes, sardines, caballa, y atún. Los numberosos dientes de que dispon nun xueguen nengún papel determinante na alimentación, ello ye que son d'amenorgáu tamañu. En llugar de dientes, el tiburón ballena zuca gran cantidá d'agua, y al cerrar la boca penerar al traviés de los sos peñes branquiales. Nel pequeñu intervalu de tiempu ente que cierra la boca y abre los sos peñes branquiales, el plancton quédase atrapáu nos dentículos dermales. Esti mecanismu de filtración previen el pasu de too fluyíu ente les branquies, y tou lo que mida más de 2 o 3 milímetros de diámetru queda atrapáu, y darréu encloyáu. Reparóse qu'estos tiburones emiten una especie de tos, que se trata d'un mecanismu de llimpieza pa espulsar l'acumuladura de partícules d'alimentos nes branquies.[6][10][11]

Alcuentra peces o concentraciones de plancton por aciu señales olfatives, pero en cuenta de tomar l'agua costantemente, ye capaz de bombiala al traviés de les sos branquies, y puede absorber l'agua a una velocidá de 1,7 l/s. El tiburón ballena nun precisa avanzar mientres s'alimenta, y munches vegaes reparar en posición vertical y moviéndose enriba y embaxo mientres bombia y penera l'agua viviegamente, al contrariu qu'el tiburón pelegrín (Cetorhinus maximus), que tien una forma más pasiva d'alimentase y nun bombia l'agua, sinón que al nadar conduz l'agua escontra les sos branquies.[6][10]

Rexúntense en redol a los petones de la mariña caribeña de Belice, complementando la so dieta diaria coles güeves del pargo cubera, que les deposita nes fases del plenilluniu y del cuartu creciente y menguante de la Lluna nos meses de mayu, xunu, y xunetu.

Esta especie, a pesar del so enorme tamañu, nun supón nengún peligru pal ser humanu. Ye un exemplu bien citáu ante la fama que tienen los tiburones de devoradores de persones. En realidá, son bastante cariñosos, y suelen ser juguetones colos buzos. Inclusive esisten informes, anque ensin confirmar, de tiburones ballena que salen a la superficie pámpana arriba por que'l buzu tásque-yos la barriga y esanície-yos los parásitos.

Esti tiburón ye reparáu bien de cutiu por buzos y por turistes a bordu de llanches frente a la península de Yucatán na isla de Holbox, nes islles de la Badea de Hondures, nes islles Maldives, les islles Galápagos d'Ecuador; en Filipines, Tailandia, la mar Bermeya, Ningaloo Reef y islla de Navidá d'Australia Occidental, Tofo Beach en Mozambique, y la badea de Sodwana en Sudáfrica. Dalgunos d'estos llugares, como por casu n'Australia Occidental, convirtiéronse en puntos centrales de la industria del ecoturismo.

La mayor concentración de tiburones ballena nel mundu atópase en Filipines. Ente los meses de xineru y mayu, arrexuntar nes mariñes pocu fondes de Donsol, na provincia de Sorsogon. Dellos buceadores bien afortunaos atoparon tiburones ballena en Puertu Ricu, en República Dominicana y les islles Seychelles. Ente avientu y setiembre, ye bien frecuente atopase con dalgún exemplar na badea de La Paz, nel estáu mexicanu de Baxa California Sur, lo mesmo que de mayu a setiembre na mariña nordés del estáu mexicanu de Quintana Roo. Dacuando acompáñenlos pequeños pexes, como la rémora. Apocayá, fueron columbraos nes proximidaes de la isla Tenggol, asitiada na mariña oeste de Malasia Peninsular, onde tamién esisten dellos petones de coral frecuentaos por estos tiburones, como la isla Redang o la isla de Kapes.

Los sos vezos reproductivos nun tán bien claros. Por aciu les observaciones d'una fema en 1910 que tenía 16 güevos n'unu de los sos oviductos deducióse equivocadamente que yeren vivíparos.[12] En 1956 realizóse l'estudiu d'un güevu na mariña de Méxicu, y tou indicaba que se trataba de seres ovíparos, pero en xunetu de 1996 afayóse una fema nes mariñes de Taiwán que tenía unos 300 güevos (el mayor númberu rexistráu de toles especies de tiburón), lo que demostraría que son ovovivíparos.[6][13][14] Les críes salen del güevu nel interior de la so madre, que-yos da a lluz vivos. Los tiburones naciellos suelen midir ente 40 y 60 centímetros de llargor, pero sábese pocu d'ellos, una y bones los exemplares nuevos déxense ver bien raramente, y nun se realizaron estudios morfométricos, nin se sabe enforma de la so tasa de crecedera. Créese qu'algamen el maduror sexual en redol a los 30 años (9 m), y que viven de media unos 100.[15]

Ye l'oxetivu de la pesca artesanal y de la industria pesquero en delles zones costeres onde se dexa ver dacuando. La población d'esta especie ye desconocida, pero ta considerada pola UICN como una especie en peligru.[1] Va Ser prohibida y penada toa pesca, vienta, importación y esportación de tiburones ballena pa propósitos comerciales. En Filipines aplícase esta llei dende 1998,[16] y en Taiwán dende mayu de 2007,[17] país onde cada añu matábense aprosimao 100 exemplares.

La principal atracción del Acuariu Kaiyukan, en Osaka, Xapón, ye un tiburón ballena, y a partir de 2005, trés exemplares tán estudiándose en cautividá nel Acuariu Churaumi de Xapón. Nel Acuariu de Xeorxa, asitiáu n'Atlanta, caltiénense cuatro más d'estos tiburones, dos machos, de nomes Taroko y Yushan, [18] y dos hembra, de nomes Alice y Trixie. N'este mesmu acuariu, Ralph y Norton, dos tiburones machos en cautividá, morrieron el 11 de xineru de 2007 y el 13 de xunu de 2007 respeutivamente.[19] Los dos machos que s'atopen na actualidá nel acuariu añedieron el 3 de xunu de 2006 coles mires d'estudiar la reproducción d'esta especie en cautividá. Los seis tiburones ballena fueron traíos dende Taiwán, onde los tiburones son un ricu y preciáu manxar por cuenta de la testura y el sabor de la so carne.[ensin referencies]

Patrones migratorios en Méxicu de tiburón ballena (Rhincodon typus).

Realizáronse dos estudios en paralelu unu nel noroeste del país y otru nel sureste.

Púdose comprobar que la especie nun tien patrones establecíos en cuanto al procesu de migración. Aprosimao'l 20 % de los tiburones ballena nueves que llega al golfu de California distribuyir ente les badees de los Ánxeles y de la Paz. Na so mayoría percuerren ente 2100 y 4900 kilómetros. Los exemplares nuevos permanecen dientro del golfu de California posiblemente pa protexese de depredadores y consiguir alimentu. Los adultos viaxen al sur y les femes preñaes dexen el golfu de California. [20]

Nun estudiu financiáu por National Geographic Society nel Llaboratoriu Marín Llamátigu de nueve años de duración hanse mapeado per vía satélite'l patrones de migración d'esta especie. Púdose reparar qu'ente mayu y setiembre nuna llocalidá al nordeste de la península de Yucatán axuntar hasta 800 exemplares nun sitiu ricu en plancton. Ellos tornen hasta dempués de seis años al mesmu sitiu y inclusive vuelven mientres dellos años consecutivos, pa distribuyise darréu en zones aledañas.

Los dolce llocalidaes principales de avistamiento allugar ente l'oeste d'Australia ya Indonesia hasta Belice pero nun pueden oldeara en cantidá cola enclavada nel Caribe. Enagora nun se tien conocencia de la so actividá mientres la metá más fría del añu. [21]

El tiburón ballena (Rhincodon typus) ye una especie d'elasmobranquiu orectolobiforme, únicu miembru de la familia Rhincodontidae y del xéneru Rhincodon. Ye'l pexe esistente más grande del mundu, con aprosimao 12 m de llargor. Habita n'agües templaes tropicales y subtropicales. Piénsase qu'habita la Tierra dende fai sesenta millones d'años.

Balina köpəkbalığı (lat. Rhincodon typus) - Orectolobiformes dəstəsinin balina köpəkbalıqları fəsiləsindən balıq növü.

40 ölkədən olan ekspertlər qrupu balina köpək balıqlarının mühafizəsi üçün bir araya gəliblər. Qeyd edək ki, bu növ planetin ən iri balıqlarıdır. Bu haqda Meksikanın Ətraf Mühitin Mühafizəsi və Təbii Sərvətlər Nazirliyindən məlumat yayılıb. Atlantik, Hind və Sakit okean tropik sularının sakinləri olan balina köpək balıqları Karib dənizinin Meksika sahillərində məskunlaşıblar. Bir çox turistlər istirahət adası olan Xolboşun yaxınlığındakı yerə suda bu canlıların ətrafında üzmək üçün gəlirlər. Bu nəhəng balıqların uzunluğu 15 metrə, kütləsi isə 20 tona yaxın olur.

Bu balıq növünün problemlərinə həsr olunmuş konfransda iştirak edən mütəxəssis – ixtioloq və ekoloqlar avqust ayının 30-u Beynəlxalq Balina Köpək balığı Günü elan olunması ilə əlaqədar razılığa gəliblər. Onların bu qərara gəlmələrində məqsəd, nəsli kəsilmə təhlükəsi olan bu növə insanların diqqətini cəlb etməkdir.

Meksika Ətraf Mühitin Mühafizəsi Nazirliyinin məlumatında qeyd olunur ki, ölkə rəhbərliyi “Yum Balam” ekoloji zonasının sərhədlərini genişləndirmək istəyir.

Balina köpəkbalığı (lat. Rhincodon typus) - Orectolobiformes dəstəsinin balina köpəkbalıqları fəsiləsindən balıq növü.

40 ölkədən olan ekspertlər qrupu balina köpək balıqlarının mühafizəsi üçün bir araya gəliblər. Qeyd edək ki, bu növ planetin ən iri balıqlarıdır. Bu haqda Meksikanın Ətraf Mühitin Mühafizəsi və Təbii Sərvətlər Nazirliyindən məlumat yayılıb. Atlantik, Hind və Sakit okean tropik sularının sakinləri olan balina köpək balıqları Karib dənizinin Meksika sahillərində məskunlaşıblar. Bir çox turistlər istirahət adası olan Xolboşun yaxınlığındakı yerə suda bu canlıların ətrafında üzmək üçün gəlirlər. Bu nəhəng balıqların uzunluğu 15 metrə, kütləsi isə 20 tona yaxın olur.

Bu balıq növünün problemlərinə həsr olunmuş konfransda iştirak edən mütəxəssis – ixtioloq və ekoloqlar avqust ayının 30-u Beynəlxalq Balina Köpək balığı Günü elan olunması ilə əlaqədar razılığa gəliblər. Onların bu qərara gəlmələrində məqsəd, nəsli kəsilmə təhlükəsi olan bu növə insanların diqqətini cəlb etməkdir.

Meksika Ətraf Mühitin Mühafizəsi Nazirliyinin məlumatında qeyd olunur ki, ölkə rəhbərliyi “Yum Balam” ekoloji zonasının sərhədlərini genişləndirmək istəyir.

El tauró balena (Rhincodon typus) és el peix més gran del món, una gegantina criatura que pot sobrepassar els 15 metres de longitud i arribar a pesar més de 20 tones. Viu en aigües càlides tropicals i subtropicals. Presenta un cos hidrodinàmic, allargat i robust, la cua pot arribar a mesurar més de 2,5 metres de costat a costat i la seva gran boca tindria la capacitat per empassar-se una foca nedant de costat. Són animals d'un color grisós fosc, amb llunars blancs o groguencs per tot el cos. És més fosc que la majoria de taurons. De la mateixa manera que les balenes, s'alimenta únicament de plàncton i de petits peixos.

El seu ventre és totalment blanc, mentre que el seu dors és d'un color grisenc, més fosc que la majoria dels taurons, amb multitud de pigues i línies horitzontals i verticals de color blanc o groguenc, de tal manera que s'assembla a un tauler d'escacs. Aquestes taques representen un patró únic en cada espècimen, per la qual cosa s'utilitzen per identificar-los i per censar la seva població. La seva pell pot arribar a tenir 10 centímetres de gruix. El seu cos és hidrodinàmic, allargat i robust, i presenta diversos ressalts longitudinals al cap i el dors. El seu cap és ample i aplanat, i en els seus laterals se situen dos petits ulls, darrere dels quals hi ha els espiracles. La seva enorme boca pot arribar a mesurar 1,5 metres d'ample, capacitat suficient com per a albergar a una foca nedant de costat, i en les seves mandíbules es troben multitud de files de petites dents. Té cinc grans parells de brànquies, les esquerdes són enormes. Posseeix un parell d'aletes dorsals i aletes pectorals, sent aquestes últimes molt poderoses. La cua d'aquests éssers pot mesurar més de 2.5 metres de costat a costat. En els taurons balena joves l'aleta superior de la cua és més gran que l'aleta inferior, en canvi la cua d'un adult té forma de mitja lluna, i és la que els proporciona la propulsió. No obstant això, el tauró balena no és un nedador eficient, ja que utilitza tot el cos per nedar, la qual cosa no sol ser freqüent en els peixos, i per això es desplaça a una velocitat mitjana de 5 km/h, una velocitat relativament lenta per un peix de tan enorme grandària.

El tauró balena viu en els oceans i mars càlids, a prop dels tròpics. Es creu que són peixos pelàgics, però en determinades temporades migren grans distàncies cap a zones costaneres, com Ningaloo Reef a Austràlia Occidental, Utila a Hondures, Donsol i Batangas a les Filipines, l'illa de Holbox en l'estat de Quintana Roo, a la Península de Yucatan, Mèxic, i les illes de l'arxipèlag de Zanzíbar (Pemba i Unguja), a la costa de Tanzània. Encara que és freqüent trobar-la mar endins, també és possible veure'la a prop de la costa, entrant en llacunes o en atolons de corall, i a prop de les desembocadures o estuaris dels rius. Sol romandre dins dels ± 30 ° de latitud, i a una profunditat de 700 metres. Sol actuar de forma solitària, encara que de tant en tant formen grups per alimentar-se en zones amb grans concentracions de menjar. Els mascles poden trobar-se en llocs més dispars, mentre que les femelles prefereixen romandre en llocs més concrets.

És una de les tres espècies de taurons que s'alimenten mitjançant un mecanisme de filtració de l'aigua, juntament amb el tauró pelegrí (Cetorhinus maximus) i el tauró bocaample (Megachasma Pelagi). S'alimenta principalment de fitoplàncton, nècton, macro algues, i krill, però de vegades també ho fa de crustacis, com larves de cranc, calamars, i bancs de peixos petits, com les anxovetes, sardines, verat, i tonyina. Les nombroses dents de què disposa no juguen cap paper determinant en l'alimentació, de fet, són de mida reduïda. En lloc de dents, el tauró balena succiona gran quantitat d'aigua, i en tancar la boca la filtra a través de les seves pintes branquials. Al petit interval de temps entre que tanca la boca i obre les seves pintes branquials, el plàncton es queda atrapat en els denticles dermals. Aquest mecanisme de filtració prevé el pas de tot fluid entre les brànquies, i tot el que mesuri més de 2 o 3 mil·límetres de diàmetre queda atrapat, i immediatament engolit. S'ha observat que aquests taurons emeten una espècie de tos, que es tracta d'un mecanisme de neteja per expulsar l'acumulació de partícules d'aliments en les brànquies.

Localitza peixos o concentracions de plàncton mitjançant senyals olfactius, però en comptes de prendre l'aigua constantment, és capaç de bombar-la a través de les seves brànquies, i pot absorbir l'aigua a una velocitat d'1,7 l/s. El tauró balena no necessita avançar mentre s'alimenta, i moltes vegades se l'observa en posició vertical i movent-se amunt i avall mentre bomba i filtra l'aigua activament, al contrari que el tauró pelegrí (Cetorhinus maximus), que té una forma més passiva d'alimentar-se i no bomba l'aigua, sinó que en nedar condueix l'aigua cap a les seves brànquies.

Els seus hàbits reproductius no estan molt clars. Mitjançant les observacions d'una femella el 1910 que tenia 16 ous en un dels seus oviductes es va deduir erròniament que eren vivípars. El 1956 es va realitzar l'estudi d'un ou a la costa de Mèxic, i tot indicava que es tractava d'éssers ovípars, però el juliol del 1996 es va descobrir una femella en les costes de Taiwan que tenia uns 300 ous (el major registrat de totes les espècies de tauró), la qual cosa demostraria que són ovovivípars. Les cries surten de l'ou a l'interior de la seva mare, que els dóna a llum vius. Els taurons nounats solen mesurar entre 40 i 60 centímetres de longitud, però se sap poc d'ells, ja que els exemplars joves es deixen veure molt rarament, i no s'han realitzat estudis morfomètrics, ni se sap molt de la seva taxa de creixement. Aconsegueixen la maduresa sexual al voltant dels 30 anys, i viuen de mitjana uns 100 anys.

El tauró balena és l'objectiu de la pesca artesanal i de la indústria pesquera a diverses zones costaneres on es deixa veure ocasionalment. La població d'aquesta espècie és desconeguda, però és considerada per la UICN com una espècie en estat vulnerable. Serà prohibida i penada tota pesca, venda, importació i exportació de taurons balena per a propòsits comercials. A les Filipines s'aplica aquesta llei des del 1998, i a Taiwan des del maig del 2007, país on cada any es mataven aproximadament 100 exemplars.

El tauró balena (Rhincodon typus) és el peix més gran del món, una gegantina criatura que pot sobrepassar els 15 metres de longitud i arribar a pesar més de 20 tones. Viu en aigües càlides tropicals i subtropicals. Presenta un cos hidrodinàmic, allargat i robust, la cua pot arribar a mesurar més de 2,5 metres de costat a costat i la seva gran boca tindria la capacitat per empassar-se una foca nedant de costat. Són animals d'un color grisós fosc, amb llunars blancs o groguencs per tot el cos. És més fosc que la majoria de taurons. De la mateixa manera que les balenes, s'alimenta únicament de plàncton i de petits peixos.

Pysgodyn mwyaf y byd yw'r morgi morfilaidd (Rhincodon typus).

Žralok obrovský (Rhincodon typus), též žralok velrybí[2], je největší žijící zástupce žraloků.[3] Obvykle dosahuje velikosti kolem osmi až devíti metrů, v mimořádných případech okolo 12 metrů.[4][5] Zprávy o exemplářích velkých až 20 metrů[6] nejsou považovány za skutečně věrohodně potvrzené, nicméně vyloučit je nelze. Nejvyšším věrohodným údajem je v současnosti míra 18,8 metru pro jedince, chyceného v Arabském moři.[7] Tento druh není člověku nebezpečný, živí se planktonem a malými rybami.[3] Vyskytuje se v tropických oblastech všech tří oceánů a může se dožít 60 až 150 let.[8]

Tato největší paryba na světě má charakteristické zbarvení - světlé skvrny a pruhy na tmavém pozadí. Její kůže může být tlustá až 10 cm.[zdroj?] Relativně velkou tlamu má umístěnou na čelní straně hlavy, napříč může mít až 2 metry a vejde se do ní až 5 lidí. Zuby jsou malé a vzadu v ústní dutině má na vnitřní straně výrůstky vytvářející jakési „síto“, v němž filtruje mořskou vodu.

Žralok obrovský je největším soudobým žralokem. Udává se, že může dorůstat až 20 m, zatím největší změřený exemplář měřil 13,7 m.[zdroj?] Na rozdíl od ostatních žraloků není nijak zvlášť dobrý plavec, obvykle se pohybuje rychlostí okolo 5 km/h.[zdroj?]

Je vejcoživorodý. V jednom vrhu samice rodí i 300 mláďat o délce okolo 0,5 m.

Žije ve vodách volných moří a oceánů tropického a subtropického pásma.

Žralok obrovský (Rhincodon typus), též žralok velrybí, je největší žijící zástupce žraloků. Obvykle dosahuje velikosti kolem osmi až devíti metrů, v mimořádných případech okolo 12 metrů. Zprávy o exemplářích velkých až 20 metrů nejsou považovány za skutečně věrohodně potvrzené, nicméně vyloučit je nelze. Nejvyšším věrohodným údajem je v současnosti míra 18,8 metru pro jedince, chyceného v Arabském moři. Tento druh není člověku nebezpečný, živí se planktonem a malými rybami. Vyskytuje se v tropických oblastech všech tří oceánů a může se dožít 60 až 150 let.

Hvalhajen (latin: Rhincodon typus), det plettede monster eller 'havets venlige kæmpe', er nok et af de mest betagende væsener, man kan opleve i havet. Desværre drives der flere steder rovdrift på den. Men nogle af de steder, hvor man tidligere dræbte hvalhajer, er en helt ny industri opstået, nemlig hvalhajsturisme. Det gælder eksempelvis i Koraltrekanten, hvor man kan dykke med hvalhajer. Hvalhajen måler normalt 12-13 meter, men der er beretninger om helt op til 18 meter lange eksemplarer. Med en maksimal vægt på op imod 21 ton er der tale om verdens største fisk. Hvalhajen føder levende unger i kuld med 100-200 unger. Ved fødslen måler ungerne 50-60 centimeter.

Hvalhajen (latin: Rhincodon typus), det plettede monster eller 'havets venlige kæmpe', er nok et af de mest betagende væsener, man kan opleve i havet. Desværre drives der flere steder rovdrift på den. Men nogle af de steder, hvor man tidligere dræbte hvalhajer, er en helt ny industri opstået, nemlig hvalhajsturisme. Det gælder eksempelvis i Koraltrekanten, hvor man kan dykke med hvalhajer. Hvalhajen måler normalt 12-13 meter, men der er beretninger om helt op til 18 meter lange eksemplarer. Med en maksimal vægt på op imod 21 ton er der tale om verdens største fisk. Hvalhajen føder levende unger i kuld med 100-200 unger. Ved fødslen måler ungerne 50-60 centimeter.

Der Walhai (Rhincodon typus) ist der größte Hai und zugleich der größte Fisch der Gegenwart. Es handelt sich um die einzige Art der Gattung Rhincodon, die wiederum die einzige Gattung innerhalb der Familie Rhincodontidae ist. Der Walhai gehört der Ordnung der Ammenhaiartigen an. Die Tiere bewohnen die tropischen bis subtropischen Meere und kommen sowohl küstennah als auch küstenfern vor. Sie ernähren sich ähnlich wie Riesenhaie und Riesenmaulhaie von Plankton und anderen Kleinstlebewesen (Krill), die sie durch Ansaugen des Wassers filtrieren.

Synonyme sind R. typicus Müller & Henle, 1839, R. pentalineatus Kishinouye, 1891, R. typus Smith, 1829, R. typus Smith, 1828 sowie Micristodus punctatus Gill, 1865.[1]

Nach Untersuchungen von 317 Individuen vor Belize wird der Walhai zwischen 3,0 und 12,7 m lang mit einem Durchschnittswert von 6,3 m.[2] Für 360 weitere Individuen am Ningaloo-Riff vor der Küste Westaustraliens, überwiegend männliche Tiere, werden Größen von 4,0 bis 12,0 m und Durchschnittswerte von 7,6 m angegeben.[3] Ein an der Küste Indiens gestrandetes Exemplar brachte es auf eine Länge von 13,7 m,[4] während ein weiteres vor Indien gefangenes Tier 14,5 m lang gewesen sein soll. Einzelnen Berichten zufolge wurden auch bis zu 18 m lange Exemplare beobachtet.[5] Eine zehnjährige Studie am Ningaloo-Riff erlaubte die Wachstumsentwicklung bei Walhaien zu studieren. Demnach nehmen männliche Tiere anfangs schnell an Körpergröße zu, die Wachstumskurve flacht dann aber ab. Ausgewachsene männliche Individuen erreichen dabei Maximallängen von 8 bis 9 m. Weibliche Tiere hingegen wachsen langsamer und kontinuierlicher und können Berechnungen zufolge bis zu 14,5 m lang werden.[6] Das Gewicht beträgt möglicherweise bis über 12 t.

Walhaie sind von gräulicher, bräunlicher oder bläulicher Farbe. Der Bauch ist hell gefärbt, der Rücken ist mit hellen Streifen und Flecken überzogen, die in Querlinien angeordnet sind. Das große Maul erstreckt sich über die gesamte Breite der abgeflachten und stumpfen Schnauze. Der Walhai hat als einziger Vertreter der Haie ein endständiges Maul. Die etwa 3600 kleinen Zähne stehen in mehr als 300 dichten Reihen angeordnet. Die Tiere besitzen fünf Kiemenspalten, zwei Rückenflossen sowie Brust- und Analflossen. Der obere Lappen der Schwanzflosse ist etwa ein Drittel länger als der untere.[7] Mit einer Dicke von bis zu 15 cm ist seine Haut die dickste aller Lebewesen der Erde.[8]

Walhaie bevorzugen eine Wassertemperatur von 21 bis 25 °C und sind weltweit in fast allen warmen, tropischen und subtropischen Gewässern anzutreffen, wobei es Regionen gibt, in denen sie gehäuft auftreten. In der Regel handelt es sich hierbei um Gebiete mit saisonaler Planktonblüte oder Regionen, in denen planktonreiches kälteres Auftriebswasser zu beobachten ist. Walhaie wandern häufig zwischen küstennahen und küstenfernen Gebieten. Männliche Tiere legen dabei beträchtliche Strecken zurück, weibliche nur kürzere; sie scheinen regelmäßig in das Gebiet ihrer Geburt zurückzukehren. Auch männliche Haie kehren immer wieder zu bestimmten Stellen zurück. Walhaie treten vereinzelt, aber auch in Gruppen auf.[9] Solche Versammlungen sind mit über 400 Individuen in einem bestimmten Gebiet vor der Küste der Halbinsel Yucatán beobachtet worden, wobei die Tiere in diesem Fall hauptsächlich an großen Aggregationen von Thunfisch-Laich fressen. Es handelt sich um die größte Ansammlung von Walhaien, die jemals gesichtet wurde und sie tritt offenbar saisonal auf.[10]

Walhaie saugen das Wasser aktiv an (bis zu 6000 l/h) und pressen es durch ihre Kiemen wieder aus, die mit einem schwammartigen Filtrierapparat versehen sind. Dieser wird aus Knorpelspangen gebildet, welche die einzelnen Kiemenbögen wie ein Gitter miteinander verbinden und auf denen untereinander verfilzte Hautzähnchen sitzen. Um ihren enormen Nahrungsbedarf zu decken, filtern sie auf diese Weise neben Plankton auch kleine Fische und andere Meeresbewohner, etwa Tintenfische, aus dem Wasser. Häufig „stehen“ sie dabei senkrecht, den Kopf zur Wasseroberfläche gerichtet im Wasser, oder sie bewegen den aus dem Wasser ragenden Kopf von einer Seite zur anderen und öffnen und schließen dabei das Maul (7–28 Mal pro Minute).[9][11]

Der Fund eines Eies mit einer Größe von circa 30 × 14 × 9 cm mit einem 36 cm großen Walhai-Embryo im Jahr 1953 im Golf von Mexiko schien die frühere Vermutung zu bestätigen, dass Walhaie zu den eierlegenden Haiarten zu rechnen seien.[1] Erst der Fang eines schwangeren Weibchens 1995 vor Taiwan und die wissenschaftliche Untersuchung dieses Exemplars ergaben, dass Walhaie bis zu 300 lebende Junge gebären können. Diese Jungen befinden sich jedoch nicht alle im selben Entwicklungsstadium, wie dies bei vielen anderen Haiarten der Fall ist. Vielmehr liegen verschiedene junge und ältere embryonale Entwicklungsformen parallel vor. Je weiter sie entwickelt sind, desto näher liegen die Jungtiere an der Geburtsöffnung. Wahrscheinlich kann das Weibchen die Entwicklung und damit die Geburt über viele Jahre hinweg steuern und gebiert nur dann, wenn sie die Überlebenschancen ihrer Jungtiere hoch einschätzt. Dies hängt vermutlich eng mit dem Nahrungsvorkommen, den Strömungen und den Temperaturen des Wassers zusammen. Diese Vermutungen sind noch nicht ausreichend belegt, jedoch die wahrscheinlichste Erklärung für diese Besonderheit. Bei dem gefundenen Ei handelte es sich wahrscheinlich um ein vorzeitig verlorenes.[1] Üblicherweise schlüpfen die Haie schon in der Gebärmutter mit einer Größe von 58 bis 64 cm. Das kleinste gefundene Exemplar hatte eine Länge von ca. 40 cm und wurde im flachen Gewässer in der Nähe der Küstenstadt Donsol in der philippinischen Provinz Sorsogon gefunden.[12][9] Möglicherweise ist das Seegebiet bei Donsol ein Aufzuchtgebiet der Walhaie.

Es lässt sich nur mutmaßen, wo die Jungen nach der Geburt ihre weitere Entwicklung bis hin zur Geschlechtsreife vollziehen. Wahrscheinlich ist, dass sie sich in größeren Tiefen weiterentwickeln. Möglicherweise unterhalb einer Tiefe von 300 Meter, da sie darüber noch Nahrungskonkurrenten für ihre erwachsenen Artgenossen darstellen könnten. Dies wäre für Jung und Alt eher von Nachteil. Möglicherweise stoßen sie in tiefere Wasserschichten vor, die ihre Eltern nicht erreichen können.

Der Walhai pflanzt sich erst im Alter zwischen 10 und 30 Jahren fort und kann bis zu 100 Jahre alt werden.

Eine Vorgängerform des heutigen Walhais wurde mit Palaeorhincodon beschrieben. Die Gattung geht auf J. Herman aus dem Jahr 1974 zurück und basiert auf Funden aus den Brüsseler und Leder Sanden in Belgien, die in das Mittlere Eozän datieren.[13] Weitere Reste stammen aus Dormaal, ebenfalls Belgien. Sie dürften aber bereits dem Unteren Eozän angehören.[14] Allgemein sind Reste von Palaeorhincodon selten, aber recht weit gestreut und kamen sowohl im südwestlichen Frankreich als auch in Nordamerika zu Tage, wo sie unter anderem aus der Fishburne-Formation in South Carolina[15] sowie aus der Hardie Mine local fauna in Georgia, beide USA, vorliegen.[16] Aus den phosphatreichen Ablagerungen des Ouled-Abdoun-Beckens in Marokko sind rund 40 Zähne geborgen worden. Sie datieren vom Oberen Paläozän bis in das Untere Eozän.[17] Weitere Zähne wurden aus dem eozänen Phosphatbecken von Kpogamé-Hahotoé in Togo berichtet.[15] Die Zähne von Palaeorhincodon sind stark gepresst und relativ klein, maximal 4 mm hoch. Die Hauptspitze ist je nach Position im Maul nach hinten (Frontalzähne) oder zur Seite (Lateralzähne) gebogen. Seitlich wird die Hauptspitze meist von je einer kleineren Nebenspitze begleitet. Letzteres unterscheidet Palaeorhincodon vom heutigen Walhai, bei dem die Nebenspitzen fehlen.[17]

Die IUCN stufte den Walhai im Jahr 2016 als stark gefährdet ein. Er befindet sich deshalb auf der roten Liste.[18] Der Populationstrend zeigt nach unten. Bedroht wird der Walhai von Fischerei, Aquakulturen, Ölbohrungen, Schiffsverkehr und Menschen, die ihm bei Freizeitaktivitäten zu nahe kommen.[19]

Walhaie können aufgrund ihrer Größe nur in sehr wenigen Aquarien weltweit gehalten werden. Außerhalb Asiens hält nur das Georgia-Aquarium in Atlanta, USA mehrere Walhaie[20]. Die Daten aus Asien sind mitunter ungenau. Vermutlich werden aktuell (02/2022) 16 Walhaie in Einrichtungen in der Volksrepublik China gehalten, ein Exemplar in Taiwan und zehn in Japanischen Aquarien[21].

Bei allen Exemplaren in menschlicher Obhut handelt es sich um Wildfänge oder gerettete Tiere. Das Georgia-Aquarium kaufte Wildfänge aus Taiwan, die sonst zu Speisezwecken verarbeitet worden wären. Einige Aquarien in Asien fangen regelmäßig neue Walhaie und lassen sie wieder frei, wenn sie eine gewisse Größe erreicht haben und durch kleinere Exemplare ersetzt werden.

Die Aquarien halten die Walhaie neben dem Attraktionscharakter auch zu Forschungszwecken. Im Zentrum steht dabei die Fortpflanzung der Walhaie[22], über die fast nichts bekannt ist. In der Wildnis konnte noch nie eine Fortpflanzung dokumentiert werden, und es wurden bisher nur einige wenige Jungtiere gefunden. Bisher kam es auch in menschlicher Obhut noch nie zu Nachwuchs, was jedoch auch mit dem noch relativ jungen Alter der gehaltenen Individuen zusammenhängen mag.

Der Walhai (Rhincodon typus) ist der größte Hai und zugleich der größte Fisch der Gegenwart. Es handelt sich um die einzige Art der Gattung Rhincodon, die wiederum die einzige Gattung innerhalb der Familie Rhincodontidae ist. Der Walhai gehört der Ordnung der Ammenhaiartigen an. Die Tiere bewohnen die tropischen bis subtropischen Meere und kommen sowohl küstennah als auch küstenfern vor. Sie ernähren sich ähnlich wie Riesenhaie und Riesenmaulhaie von Plankton und anderen Kleinstlebewesen (Krill), die sie durch Ansaugen des Wassers filtrieren.

Synonyme sind R. typicus Müller & Henle, 1839, R. pentalineatus Kishinouye, 1891, R. typus Smith, 1829, R. typus Smith, 1828 sowie Micristodus punctatus Gill, 1865.

Gōng-á-soa ia̍h-sī kiò Tāu-hū-soa[1] (ha̍k-miâ: Rhincodon typus, Eng-gí: Whale Shark) sī sè-kan siāng toā chiah ê oa̍h hî. Chit chióng soa-hî sèng-tē un-sûn, tōng-chok sô, oân-choân khò thai (filter) sió seng-bu̍t chhoē chia̍h. I sī Rhincodon sio̍k kap Rhincodontidae kho î-it ê chéng. Gōng-á-soa tī jia̍t-tāi hù-kīn ê sio-lo̍h hái-chúi ū tè chhoē. Kho-ha̍k-kài jīn-ûi í-keng tī-teh 6-chheng-bān nî.

Gōng-á-soa ê toā-sè khó-pí hái-ang, thó-chia̍h ê hêng-ûi mā chhan-chhiūⁿ chi̍t-koá hái-ang.

Gōng-á-soa ia̍h-sī kiò Tāu-hū-soa (ha̍k-miâ: Rhincodon typus, Eng-gí: Whale Shark) sī sè-kan siāng toā chiah ê oa̍h hî. Chit chióng soa-hî sèng-tē un-sûn, tōng-chok sô, oân-choân khò thai (filter) sió seng-bu̍t chhoē chia̍h. I sī Rhincodon sio̍k kap Rhincodontidae kho î-it ê chéng. Gōng-á-soa tī jia̍t-tāi hù-kīn ê sio-lo̍h hái-chúi ū tè chhoē. Kho-ha̍k-kài jīn-ûi í-keng tī-teh 6-chheng-bān nî.

Gōng-á-soa ê toā-sè khó-pí hái-ang, thó-chia̍h ê hêng-ûi mā chhan-chhiūⁿ chi̍t-koá hái-ang.

Ang isdantuko o butanding (Ingles: whale shark, literal na "balyenang pating")[2], may pangalang pang-agham na Rhincodon typus[3], ay mga uri ng isdang pating na kahawig ng mga balyena at tuko. Nananala lamang sa tubig ang mga ito, habang lumalangoy, ng kanilang pagkain.

![]() Ang lathalaing ito ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Ang lathalaing ito ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Ang isdantuko o butanding (Ingles: whale shark, literal na "balyenang pating"), may pangalang pang-agham na Rhincodon typus, ay mga uri ng isdang pating na kahawig ng mga balyena at tuko. Nananala lamang sa tubig ang mga ito, habang lumalangoy, ng kanilang pagkain.

De Waalhai (Rhincodon typus) is de gröttste Hai un ok de gröttste Fisch op de Eer. De gröötste Hai, de bet hüüt fangen worrn is, weer 13,7 Meter lang. De swoorste hett 36.000 Kilogramm op de Waag brocht. Ok wenn he groot is, is he doch kene Gefohr. Waalhaien freet blot Plankton un annere lütte Veecher, de se ut dat Water rutfiltert.

De Waalhai is de eenzige Oort in dat Geslecht Rhincodon, de wedder dat eenzige Geslecht in de Familie vun de Waalhaien in de Ornen Orectolobiformes is.

De Waalhaien hebbt en griese, brune oder blage Klöör. De Buuk is dorbi heller un över den Rügg gaht helle Striepen un Placken. De Waalhaien hebbt twee Finnen op’n Rügg, Bost- un Oorsfinnen un fief Kemen. Dat grote Muul reckt över de ganze Breed vun de flache Snuut.

Waalhaien hebbt en Watertemperatur vun 21 bet 25 °C geern un leevt op de ganze Welt in temlich all de warmen, tropischen oder subtropischen Meren. In Regionen mit saisonale Planktonblöten oder wo koolt Water mit veel Plankton opstiggt kaamt se teemlich faken vör.

De Waalhaien suugt dat Water an un presst dat dör ehre Kemen, de en Filterapparat ut Gnurpelspangen hebbt. Op disse Gnurpelspangen sitt lütte Huuttähn, an de dat Plankton hingen blifft.

Lang weer nich seker, of de Waalhai Eier liggt oder siene Jungen lebennig op de Welt bringt. Eerst nadem Wetenschoplers 1995 vör Taiwan en drächtig Seken fungen un ünnersöcht hebbt, hebbt se rutfunnen, dat de Waalhai bet to 300 lebennige Junge op de Welt bringt.

De Waalhai (Rhincodon typus) is de gröttste Hai un ok de gröttste Fisch op de Eer. De gröötste Hai, de bet hüüt fangen worrn is, weer 13,7 Meter lang. De swoorste hett 36.000 Kilogramm op de Waag brocht. Ok wenn he groot is, is he doch kene Gefohr. Waalhaien freet blot Plankton un annere lütte Veecher, de se ut dat Water rutfiltert.

De Waalhai is de eenzige Oort in dat Geslecht Rhincodon, de wedder dat eenzige Geslecht in de Familie vun de Waalhaien in de Ornen Orectolobiformes is.

De Waalhaien hebbt en griese, brune oder blage Klöör. De Buuk is dorbi heller un över den Rügg gaht helle Striepen un Placken. De Waalhaien hebbt twee Finnen op’n Rügg, Bost- un Oorsfinnen un fief Kemen. Dat grote Muul reckt över de ganze Breed vun de flache Snuut.

Di Waalhei (Rhincodon typus) as di gratst hei an uk di gratst fask üüb a eerd. Hias di iansagst slach uun det skööl faan a waalheier (Rhincodon), an det as det iansagst skööl uun't famile Rhincodontidae.

Hi lewet faan plankton an koon muar üs 10 m lung wurd an muar üs 10 t swaar.

Di Waalhei (Rhincodon typus) as di gratst hei an uk di gratst fask üüb a eerd. Hias di iansagst slach uun det skööl faan a waalheier (Rhincodon), an det as det iansagst skööl uun't famile Rhincodontidae.

Hi lewet faan plankton an koon muar üs 10 m lung wurd an muar üs 10 t swaar.

D'Walhaie (Rhincodon typus) sinn déi gréisst vun den Haienaarten, déi haut existéieren, an och déi gréisst lieweg Fësch.

Dat gréisst Exemplar dat bis haut gemooss gouf war 13,7 m laang, et sollen awer och nach méi grousser gesi gi sinn. Walhaien erniere sech vu Plankton an anerem ganz klengem Gedéiesch, andeems se Waasser asuckelen a filtréieren. Se sinn deemno ongeféierlech fir de Mënsch.

De Walhai ass déi eenzeg Aart vun der Gattung Rhincodon, déi hirersäits déi eenzeg Gattung bannent der Famill Rhincodontidae ass.

Walhaien hunn eng groelzeg, brongelzeg oder bloelzeg Faarf. De Bauch ass hell gefierft, um Réck si Flecken a Sträifen, déi queesch Linne bilden. Seng grouss Maul geet iwwer déi ganz Breet vu senger flaacher Schnëss. Se huet eng 3.600 kleng Zänn, déi an enger 300 Reien no beienee stinn.

Walhaie sinn ronderëm d'Welt a waarmen, tropeschen a subtropesche Mierer ze fannen. Se planze sech eréischt am Alter tëscht 10 an 30 Joer virun a kënnen alt 100 Joer al ginn.

D'Walhaie (Rhincodon typus) sinn déi gréisst vun den Haienaarten, déi haut existéieren, an och déi gréisst lieweg Fësch.

Dat gréisst Exemplar dat bis haut gemooss gouf war 13,7 m laang, et sollen awer och nach méi grousser gesi gi sinn. Walhaien erniere sech vu Plankton an anerem ganz klengem Gedéiesch, andeems se Waasser asuckelen a filtréieren. Se sinn deemno ongeféierlech fir de Mënsch.

De Walhai ass déi eenzeg Aart vun der Gattung Rhincodon, déi hirersäits déi eenzeg Gattung bannent der Famill Rhincodontidae ass.

Walhaien hunn eng groelzeg, brongelzeg oder bloelzeg Faarf. De Bauch ass hell gefierft, um Réck si Flecken a Sträifen, déi queesch Linne bilden. Seng grouss Maul geet iwwer déi ganz Breet vu senger flaacher Schnëss. Se huet eng 3.600 kleng Zänn, déi an enger 300 Reien no beienee stinn.

Walhaie sinn ronderëm d'Welt a waarmen, tropeschen a subtropesche Mierer ze fannen. Se planze sech eréischt am Alter tëscht 10 an 30 Joer virun a kënnen alt 100 Joer al ginn.

Ο φαλαινοκαρχαρίας (Rhincodon typus - Ρυγχόδων ο τύπος) είναι ένας αργά κινούμενος καρχαρίας που τρέφεται φιλτράροντας την τροφή του και είναι το μεγαλύτερο ψάρι στον κόσμο, στα οποία χαρακτηριστικά οφείλεται και το όνομά του. Μπορεί να φτάσει μέχρι τα 12.6 μ (41 πόδια) μήκος και βάρος 21.5 τόνους.[1]

Αυτός ο ευδιάκριτα σημαδεμένος καρχαρίας είναι το μόνο μέλος του γένους του, Rhincodon και της οικογένειά του, Ρινκοδοντίδες (Rhincodontidae) (που καλούταν Ρινκόδοντες (Rhinodontes) πριν από το 1984), το οποίο ομαδοποιείται στην ομοταξία Ελασμοβράχιοι στην συνομοταξία Χονδριχθύες. Ο φαλαινοκαρχαρίας ζει στους τροπικούς και θερμούς ωκεανούς και ζει στην ανοικτή θάλασσα και μπορεί να ζήσει για περίπου 70 έτη. Το είδος θεωρείται ότι έχει εμφανιστεί περίπου πριν από 60 εκατομμύρια έτη.

Οι φαλαινοκαρχαρίες τρέφονται κυρίως, αν όχι αποκλειστικά, με πλαγκτόν, τα οποία είναι μικροσκοπικά φυτά και ζώα, αν και στη σειρά του BBC Planet Earth φαίνεται ότι τρώει από ένα κοπάδι μικρών ψαριών.[2] Θεωρείται από τη IUCN ως ευάλωτο είδος και ο αριθμός των φαλαινοκαρχαριών δεν είναι γνωστός[3].

Ο φαλαινοκαρχαρίας (Rhincodon typus - Ρυγχόδων ο τύπος) είναι ένας αργά κινούμενος καρχαρίας που τρέφεται φιλτράροντας την τροφή του και είναι το μεγαλύτερο ψάρι στον κόσμο, στα οποία χαρακτηριστικά οφείλεται και το όνομά του. Μπορεί να φτάσει μέχρι τα 12.6 μ (41 πόδια) μήκος και βάρος 21.5 τόνους.

Αυτός ο ευδιάκριτα σημαδεμένος καρχαρίας είναι το μόνο μέλος του γένους του, Rhincodon και της οικογένειά του, Ρινκοδοντίδες (Rhincodontidae) (που καλούταν Ρινκόδοντες (Rhinodontes) πριν από το 1984), το οποίο ομαδοποιείται στην ομοταξία Ελασμοβράχιοι στην συνομοταξία Χονδριχθύες. Ο φαλαινοκαρχαρίας ζει στους τροπικούς και θερμούς ωκεανούς και ζει στην ανοικτή θάλασσα και μπορεί να ζήσει για περίπου 70 έτη. Το είδος θεωρείται ότι έχει εμφανιστεί περίπου πριν από 60 εκατομμύρια έτη.

Οι φαλαινοκαρχαρίες τρέφονται κυρίως, αν όχι αποκλειστικά, με πλαγκτόν, τα οποία είναι μικροσκοπικά φυτά και ζώα, αν και στη σειρά του BBC Planet Earth φαίνεται ότι τρώει από ένα κοπάδι μικρών ψαριών. Θεωρείται από τη IUCN ως ευάλωτο είδος και ο αριθμός των φαλαινοκαρχαριών δεν είναι γνωστός.

Кит-ајкула (Rhincodon typus) е вид на ајкула.

Китот-ајкула е најголемата риба во светот. Широка 1,5 м, нејзината уста е доволно голема внатре да собере човек. Но таа е безопасен процедувач: се храни само со планктон и со мали риби. За да добие големо количество храна што и е потребно, ја вцицува водата в уста, а потоа ја црпи преку жабрите каде што честичките храна се задржуваат на коскените изостатоци наречени жабрени шипки, а потоа ги проголтува. Оваа ајкула има најдебела кожа од сите животни, дебела и до 10 цм. По должината на нејзиното тело се протегаат испакнати гребени, а има голема, српеста опашка. Дезенот со бели дамки на нејзиниот грб е уникатен кај секоја риба, што на научниците им овозможува да ги препознаат единките со анализа на фотографиите. Иако малку се знае за нивните океански патувања, со сателитско следење е откриено дека некои кит-ајкули мигрираат преку целиот океан. Јајцата на оваа ајкула се развиваат заради месото и перките (се користат за супа), иако во некои земји се заштитени со закон.

Кит-ајкула (Rhincodon typus) е вид на ајкула.

Китот-ајкула е најголемата риба во светот. Широка 1,5 м, нејзината уста е доволно голема внатре да собере човек. Но таа е безопасен процедувач: се храни само со планктон и со мали риби. За да добие големо количество храна што и е потребно, ја вцицува водата в уста, а потоа ја црпи преку жабрите каде што честичките храна се задржуваат на коскените изостатоци наречени жабрени шипки, а потоа ги проголтува. Оваа ајкула има најдебела кожа од сите животни, дебела и до 10 цм. По должината на нејзиното тело се протегаат испакнати гребени, а има голема, српеста опашка. Дезенот со бели дамки на нејзиниот грб е уникатен кај секоја риба, што на научниците им овозможува да ги препознаат единките со анализа на фотографиите. Иако малку се знае за нивните океански патувања, со сателитско следење е откриено дека некои кит-ајкули мигрираат преку целиот океан. Јајцата на оваа ајкула се развиваат заради месото и перките (се користат за супа), иако во некои земји се заштитени со закон.

Китсыман акула (лат. Rhincodon typus) - акулалар төренә керүче кимерчәкле балык.

Китсыман акула җылы сулы диңгезләрдә һәм океаннарда яши. Ул — Җир шарындагы иң зур балык: озынлыгы 20 метрга, авырлыгы 21 тоннага кадәр җитә. Бик әкрен йөзә. зур гәүдәле булса да, планктон, диңгез йөрәге һәм вак балыклар белән туклана.

Китсыман акуланың авыз киңлеге 2 метрга кадәр җитә. Аның йөзгәндә һәрвакыт авызы ачык була, һәм ул юлында очраган һәр планктон яисә вак балыкны йота бара.

Китсыман акула (лат. Rhincodon typus) - акулалар төренә керүче кимерчәкле балык.

Китсыман акула җылы сулы диңгезләрдә һәм океаннарда яши. Ул — Җир шарындагы иң зур балык: озынлыгы 20 метрга, авырлыгы 21 тоннага кадәр җитә. Бик әкрен йөзә. зур гәүдәле булса да, планктон, диңгез йөрәге һәм вак балыклар белән туклана.

Китсыман акуланың авыз киңлеге 2 метрга кадәр җитә. Аның йөзгәндә һәрвакыт авызы ачык була, һәм ул юлында очраган һәр планктон яисә вак балыкны йота бара.

ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ( ਰਿੰਕੋਡਨ ਟਾਈਪਸ ) ਇੱਕ ਹੌਲੀ ਚਲਦੀ, ਫਿਲਟਰ-ਫੀਡਿੰਗ ਕਾਰਪੇਟ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ਅਤੇ ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਵੱਡੀ ਜਾਣੀ ਜਾਂਦੀ ਮੌਜੂਦਾ ਮੱਛੀ ਪ੍ਰਜਾਤੀ ਹੈ। ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਵੱਧ ਪੁਸ਼ਟੀ ਕੀਤੇ ਮੱਛੀ ਦੀ ਲੰਬਾਈ 18.8 ਮੀ (62 ਫ਼ੁੱਟ)ਸੀ [1] ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ਨੇ ਜਾਨਵਰਾਂ ਦੇ ਰਾਜ ਵਿੱਚ ਅਕਾਰ ਦੇ ਲਈ ਬਹੁਤ ਸਾਰੇ ਰਿਕਾਰਡ ਰੱਖੇ ਹਨ। 1984 ਤੋਂ ਪਹਿਲਾਂ ਇਸ ਨੂੰ ਰਾਈਨੋਡੋਂਟੀ ਵਿਚ ਰਾਈਨਿਓਡਨ ਵਜੋਂ ਸ਼੍ਰੇਣੀਬੱਧ ਕੀਤਾ ਗਿਆ ਸੀ।

ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ਗਰਮ ਦੇਸ਼ਾਂ ਦੇ ਖੁੱਲੇ ਪਾਣੀਆਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਪਾਈ ਜਾਂਦੀ ਹੈ ਅਤੇ 21 °C (70 °F) ਤੋਂ ਘੱਟ ਪਾਣੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਘੱਟ ਹੀ ਪਾਈ ਜਾਂਦੀ ਹੈ। ਮਾਡਲਿੰਗ ਤਕਰੀਬਨ 70 ਸਾਲਾਂ ਦੀ ਉਮਰ ਦਾ ਸੁਝਾਅ ਦਿੰਦੀ ਹੈ, ਅਤੇ ਜਦੋਂ ਕਿ ਮਾਪਾਂ ਮੁਸ਼ਕਲ ਸਾਬਤ ਹੋਈਆਂ ਹਨ, [2] ਫੀਲਡ ਡੇਟਾ ਤੋਂ ਅਨੁਮਾਨ ਦੱਸਦੇ ਹਨ ਕਿ ਉਹ ਸ਼ਾਇਦ 130 ਸਾਲਾਂ ਤੱਕ ਜੀ ਸਕਦੇ ਹਨ। [3] ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ਦੇ ਬਹੁਤ ਵੱਡੇ ਮੂੰਹ ਹਨ ਅਤੇ ਫਿਲਟਰ ਫੀਡਰ ਹਨ, ਜੋ ਕਿ ਇੱਕ ਫੀਡਿੰਗ ਮੋਡ ਹੈ ਜੋ ਸਿਰਫ ਦੋ ਹੋਰ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ, ਮੈਗਾਮੌਥ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ਅਤੇ ਬਾਸਕਿੰਗ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ਵਿੱਚ ਹੁੰਦਾ ਹੈ। ਉਹ ਲਗਭਗ ਕੇਵਲ ਪਲੇਂਕਟਨ ਅਤੇ ਛੋਟੀਆਂ ਮੱਛੀਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਖਾਣਾ ਬਣਾਉਂਦੇ ਹਨ, ਅਤੇ ਮਨੁੱਖਾਂ ਲਈ ਕੋਈ ਖਤਰਾ ਨਹੀਂ ਹਨ।

ਅਪ੍ਰੈਲ 1828 ਵਿਚ ਸਪੀਸੀਜ਼ ਦੀ ਪਛਾਣ ਕੀਤੀ ਗਈ। ਨਮੂਨਾ ਟੇਬਲ ਬੇ, ਸਾ ਊਥ ਅਫਰੀਕਾ ਵਿੱਚ ਸੀ। ਕੇਪਟਾ ਟਾਊਨ ਵਿੱਚ ਤਾਇਨਾਤ ਬ੍ਰਿਟਿਸ਼ ਫੌਜਾਂ ਨਾਲ ਜੁੜੇ ਇੱਕ ਮਿਲਟਰੀ ਡਾਕਟਰ ਐਂਡਰ ਸਮਿੱਥ ਨੇ ਅਗਲੇ ਸਾਲ ਇਸ ਦਾ ਵਰਣਨ ਕੀਤਾ। [4] "ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ" ਨਾਮ ਮੱਛੀ ਦੇ ਆਕਾਰ ਨੂੰ ਦਰਸਾਉਂਦਾ ਹੈ, ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਦੀਆਂ ਕੁਝ ਕਿਸਮਾਂ ਜਿੰਨਾ ਵੱਡਾ ਹੁੰਦਾ ਹੈ, [5] ਅਤੇ ਇਸ ਨੂੰ ਬਾਲਿਨ ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਵਾਂਗ ਫਿਲਟਰ ਫੀਡਰ ਵੀ ਮੰਨਿਆ ਜਾਂਦਾ ਹੈ।

ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ਦਾ ਮੂੰਹ ਹੁੰਦਾ ਹੈ ਜੋ 1.5 ਮੀ (4.9 ਫ਼ੁੱਟ) ਚੌੜਾ ਹੋ ਸਕਦਾ ਹੈ। [6] 300 ਤੋਂ ਵੱਧ ਕਤਾਰਾਂ ਵਾਲੇ ਛੋਟੇ ਦੰਦ ਅਤੇ 20 ਫਿਲਟਰ ਪੈਡ ਜਿਸ ਨੂੰ ਇਹ ਫਿਲਟਰ ਕਰਨ ਲਈ ਵਰਤਦੀਹੈ। [7] ਕਈ ਹੋਰ ਸ਼ਾਰਕਾਂ ਦੇ ਉਲਟ, ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ਦੇ ਮੂੰਹ ਸਿਰ ਦੇ ਥੱਲੇ ਜਾਣ ਦੀ ਬਜਾਏ ਸਿਰ ਦੇ ਅਗਲੇ ਪਾਸੇ ਹੁੰਦੇ ਹਨ। [8] ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ਵਿਚ ਪੰਜ ਵੱਡੀਆਂ ਜੋੜੀਆਂ ਗਿੱਲ ਹਨ। ਸਿਰ ਚੌਗਿਰਦਾ ਹੈ ਅਤੇ ਅਗਲੇ ਕੋਨੇ 'ਤੇ ਦੋ ਛੋਟੀਆਂ ਅੱਖਾਂ ਵਾਲਾ ਫਲੈਟ ਹੈ। ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ਚਿੱਟੇ ਢਿੱਡ ਦੇ ਨਾਲ ਗੂੜ੍ਹੇ ਸਲੇਟੀ ਹੁੰਦੇ ਹਨ। ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੀ ਚਮੜੀ ਨੂੰ ਫ਼ਿੱਕੇ ਸਲੇਟੀ ਜਾਂ ਚਿੱਟੇ ਧੱਬਿਆਂ ਅਤੇ ਧਾਰੀਆਂ ਨਾਲ ਨਿਸ਼ਾਨਬੱਧ ਕੀਤਾ ਗਿਆ ਹੈ ਜੋ ਹਰੇਕ ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਲਈ ਵਿਲੱਖਣ ਹਨ।ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ਦੇ ਇਸਦੇ ਪਾਸਿਆਂ ਤੇ ਤਿੰਨ ਪ੍ਰਮੁੱਖ ਧਾਰੀਆਂ ਹਨ, ਜੋ ਕਿ ਸਿਰ ਦੇ ਉੱਪਰ ਅਤੇ ਪਿਛਲੇ ਪਾਸੇ ਸ਼ੁਰੂ ਹੁੰਦੀਆਂ ਹਨ ਅਤੇ ਦੁਪੱਟ ਪੈਡਨਕਲ ਤੇ ਖਤਮ ਹੁੰਦੀਆਂ ਹਨ। ਇਸ ਦੀ ਚਮੜੀ 15 ਸੈਟੀਮੀਟਰ ਮੋਟੀ ਹੈ ਅਤੇ ਬਹੁਤ ਹੀ ਸਖਤ ਹੈ। ਵ੍ਹੇਲ ਸ਼ਾਰਕ ਦੀਆਂ ਝਿੱਲੀਆਂ ਇਸ ਦੀਆਂ ਅੱਖਾਂ ਦੇ ਬਿਲਕੁਲ ਪਿੱਛੇ ਹਨ।

திமிங்கலச் சுறா (Rhincodon typus) என்பது உலகில் உள்ள மீன்கள் யாவற்றினும் மிகப்பெரிய வகை மீன் ஆகும். இச் சுறாமீன் வெப்ப மண்டலக் கடல்களில் வாழ்கின்றன. நிலநடுக்கோட்டிலிருந்து சுமார் ±30° பகுதிகளில் வாழ்கின்றன. சுமார் 700 மீட்டர் ஆழத்தில் வாழ்கின்றன. இவை வாழும் கடற்பகுதிகளை படத்தில் காணலாம்.

இச் சுறா மீன்கள் சுமார் 18 மீட்டர் (60 அடிகள்) நீளமும் சுமார் 14 மெட்ரிக் டன் எடையும் கொண்டவை. இவை தனியாகவே வாழ்கின்றன. ஒரு நாளைக்கு 2.6 டன் எடை உணவு உட்கொள்ளும்.

சுமார் 60 மில்லியன் ஆண்டுகளுக்கு முன்பே தோன்றிய மீன் இனம் என்பர்.[2]

திமிங்கலச் சுறா (Rhincodon typus) என்பது உலகில் உள்ள மீன்கள் யாவற்றினும் மிகப்பெரிய வகை மீன் ஆகும். இச் சுறாமீன் வெப்ப மண்டலக் கடல்களில் வாழ்கின்றன. நிலநடுக்கோட்டிலிருந்து சுமார் ±30° பகுதிகளில் வாழ்கின்றன. சுமார் 700 மீட்டர் ஆழத்தில் வாழ்கின்றன. இவை வாழும் கடற்பகுதிகளை படத்தில் காணலாம்.

இச் சுறா மீன்கள் சுமார் 18 மீட்டர் (60 அடிகள்) நீளமும் சுமார் 14 மெட்ரிக் டன் எடையும் கொண்டவை. இவை தனியாகவே வாழ்கின்றன. ஒரு நாளைக்கு 2.6 டன் எடை உணவு உட்கொள்ளும்.

சுமார் 60 மில்லியன் ஆண்டுகளுக்கு முன்பே தோன்றிய மீன் இனம் என்பர்.

An butanding (ingles, whale shark, Rhincodon typus) sarong klaseng sira' na konsideradong iyo na an pinakadakula asin ini minimidbid na sarong pating. Pigsasara' niya an saiyang pagkakan paagi sa pagbuka kan dakula niyang nguso.

An konpirmadong naisihan na pagkadakula nag'abot sa laba' na 12.65 metro (41.50 pie) na may gabat 21.5 tonelada (47,000 libra), dawa igwa pang mga inoosip na mas dakula pa kaini. An pating na ini, na burikbutikon iyo sana an myembro kan genus Rhincodon' asin kan saiyang pamilya, Rhincodontidae na nasa lindong kan subklaseng Elasmobranchii, sa laog kan klaseng Chondrichthyes.

An sirang ini nakukua sa mga tropikal asin mga maiimbong na dagat, asin nagbubuhay sa kahiwasan kan dagat na may lawig-buhay naabot 70ng taon. An species na ini nagpoon mabuhay kaidto pang 60 milyon na taon. Dawa kadakula an nguso, an butanding haros kinakakan sana mga plankton, mga tanom na mikroskopiko asin sarosaradit na hayop sa dagat.

An sugok kan butanding nahimsa sa laog mansana kan tulak kan inang butanding. Iyo na daa ini an pinakadakulang sugok sa mga sira. [1]

An species na ini nabisto kan madakop an sarong butanding 4.6 na metro (15.1 pie) an pagkalaba kan Abril 1828 duman sa Table Bay, South Africa. Si Andrew Smith, sarong doktor na militar kabali sa mga tropang Britanya nakabase sa Cape Town pinagladawan na gayo an saiyang hitsura kan taon 1829. Nagpaluwas siya nin libro dapit sa sira na ini kan taon 1849 na pigdetalye niyang marhay an hitsura kaini.

Sa relihiyon kan Byetnam, ini pigtitingag na sarong diyos-diyos, nagngangaran na "Ca Ong", na boot sabihon, "Kagurangnan na Sira".

Sa Mehiko asin sa dakul na parte kan Latin Amerika, an butanding inaapod na "pez dama" o "domino" huli sa mga burikbutik niya. Sa Aprika an mga apod kaini maladawan na gayo- "papa shillingi" sa Kenya, huli daa ta an Diyos nagdaklag nin mga shillings (mga sensilyo) sa sira asin an mga ini nagdurukot asin iyo na an mga burikbutik. Sa Madagaskar, inaapod ining "marokintana", na an kahulogan, "dakul na bitoon".

An mga taga-Java pigtotomoyan man an mga bitoon ta inapod man ninda an butanding na "geger lintang", o "mga bitoon sa likod" daa.

Sa Donsol, Sorsogon kan Filipinas bantogan nang gayo an butanding asin ipigtotolod ini bilang pangturistang atraksyon. Pigprograma kan gobyerno lokal na mapakarhay an pagdalan asin pagrani sa mga butanding sa kadagatan bilang proyektong eko-turismo. An mga butanding maboot asin bako lamang ma'olyas na hayop mala ta pwede ranihan asin hapiyapon. An sirang ini dayo asin hale pa sa hararayong dagat. Natipon ining dakul sa Donsol poon Nobyembre abot Mayo na noto'dan man kan mga turista na magroso' sa siring na panahon sa pagdalan kan mga maboot na sira.

Bago naglaog an gobyerno lokal asin naki-aram sa pagligtas sa butanding na dai mapuho kan mga parasira, an sira na ini namiligro na maubos sa kadagatan kan Sorsogon. An sira na ini binabakal kan mga Intsik na mga taga-Taiwan ta pigtutubod na delicacy asin pampagana sa sex asin an naggugurang nang butanding (mga 30 anyos edad) nagkakahalaga nin Php 400,000. An laman kaini nagprepresyong HK$500 o Php 1,700 an kilo.[2]

Kaamayi pa kan mga taon na 1600 naonambitan na ni Lisboa an hayop na ini sa dagat.[3]

An butanding (ingles, whale shark, Rhincodon typus) sarong klaseng sira' na konsideradong iyo na an pinakadakula asin ini minimidbid na sarong pating. Pigsasara' niya an saiyang pagkakan paagi sa pagbuka kan dakula niyang nguso.

An konpirmadong naisihan na pagkadakula nag'abot sa laba' na 12.65 metro (41.50 pie) na may gabat 21.5 tonelada (47,000 libra), dawa igwa pang mga inoosip na mas dakula pa kaini. An pating na ini, na burikbutikon iyo sana an myembro kan genus Rhincodon' asin kan saiyang pamilya, Rhincodontidae na nasa lindong kan subklaseng Elasmobranchii, sa laog kan klaseng Chondrichthyes.

An sirang ini nakukua sa mga tropikal asin mga maiimbong na dagat, asin nagbubuhay sa kahiwasan kan dagat na may lawig-buhay naabot 70ng taon. An species na ini nagpoon mabuhay kaidto pang 60 milyon na taon. Dawa kadakula an nguso, an butanding haros kinakakan sana mga plankton, mga tanom na mikroskopiko asin sarosaradit na hayop sa dagat.

An sugok kan butanding nahimsa sa laog mansana kan tulak kan inang butanding. Iyo na daa ini an pinakadakulang sugok sa mga sira.

Yèe bintang nakeuh salah saboh jeunèh yèe nyang jipajôh plankton. Eungkôt nyoe nakeuh eungkôt paléng rayek bak bumoe.

Eungkôt yèe nyoe udép di la'ôt tropis ngön la'ôt nyang iklimjih hangat. Yèe bintang jeuet jiudép trôk 'an umu 70 thôn.

The whale shark (Rhincodon typus) is a slow-moving, filter-feeding carpet shark and the largest known extant fish species. The largest confirmed individual had a length of 18.8 m (61.7 ft).[8] The whale shark holds many records for size in the animal kingdom, most notably being by far the largest living nonmammalian vertebrate. It is the sole member of the genus Rhincodon and the only extant member of the family Rhincodontidae, which belongs to the subclass Elasmobranchii in the class Chondrichthyes. Before 1984 it was classified as Rhiniodon into Rhinodontidae.

The whale shark is found in open waters of the tropical oceans and is rarely found in water below 21 °C (70 °F).[2] Studies looking at vertebral growth bands and the growth rates of free-swimming sharks have estimated whale shark lifespans at 80–130 years.[9][10][11] Whale sharks have very large mouths and are filter feeders, which is a feeding mode that occurs in only two other sharks, the megamouth shark and the basking shark. They feed almost exclusively on plankton and small fishes and pose no threat to humans.

The species was distinguished in April 1828 after the harpooning of a 4.6 m (15 ft) specimen in Table Bay, South Africa. Andrew Smith, a military doctor associated with British troops stationed in Cape Town, described it the following year.[12] The name "whale shark" refers to the fish's size: it is as large as some species of whale.[13] In addition, its filter feeding habits are not unlike those of baleen whales.

Whale sharks possess a broad, flattened head with a large mouth and two small eyes located at the front corners.[14][15] Unlike many other sharks, whale shark mouths are located at the front of the head rather than on the underside of the head.[16] A 12.1 m (39.7 ft) whale shark was reported to have a mouth 1.55 m (5.1 ft) across.[17] Whale shark mouths can contain over 300 rows of tiny teeth and 20 filter pads which it uses to filter feed.[18] The spiracles are located just behind the eyes. Whale sharks have five large pairs of gills. Their skin is dark grey with a white belly marked with an arrangement of pale grey or white spots and stripes that is unique to each individual. The skin can be up to 15 cm (5.9 in) thick and is very hard and rough to the touch. The whale shark has three prominent ridges along its sides, which start above and behind the head and end at the caudal peduncle.[15] The shark has two dorsal fins set relatively far back on the body, a pair of pectoral fins, a pair of pelvic fins and a single medial anal fin. The caudal fin has a larger upper lobe than the lower lobe (heterocercal).

Whale sharks have been found to possess dermal denticles on the surface of their eyeballs that are structured differently from their body denticles. The dermal denticles, as well as the whale shark's ability to retract its eyes deep into their sockets, serve to protect the eyes from damage.[19][20]

Evidence suggests that whale sharks can recover from major injuries and may be able to regenerate small sections of their fins. Their spot markings have also been shown to reform over a previously wounded area.[21]

The complete and annotated genome of the whale shark was published in 2017.[22]

Rhodopsin, the light-sensing pigment in the rod cells of the retina, is normally sensitive to green and used to see in dim light. But in whale sharks (and bottom-dwelling cloudy catsharks), two amino acid substitutions has made the pigment more sensitive to blue light instead, the light that dominates the deep ocean. One of these mutations also makes rhodopsin vulnerable to higher temperatures. In humans a similar mutation leads to congenital stationary night blindness, as the human body temperature makes the pigment decay.[23][24] To protect this pigment which becomes unstable in shallow water, where the temperature is higher and the full spectrum of light is present, as otherwise the pigment would hinder full color vision, the shark deactivates it. In the colder environment at 2,000 meters below the surface where the shark dives, it is activated again.[25] The mutations thus allow the shark to see well at both ends of its great vertical range.[26][27] The eyes have also lost all cone opsins except LWS.[28]

The whale shark is the largest non-cetacean animal in the world. Evidence suggests that whale sharks exhibit sexual dimorphism with regards to size, with females growing larger than males. A 2020 study looked at the growth of whale shark individuals over a 10-year period. It concluded that males on average reach 8 to 9 meters (26 to 30 ft) in length. The same study predicted females to reach a length of around 14.5 m (48 ft) on average, based on more limited data. However, these are averages and do not represent the maximum possible sizes.[29] Previous studies estimating the growth and longevity of whale sharks have produced estimates ranging from 14 to 21.9 meters (46 to 72 ft) in length.[9][11][30][31] Limited evidence, mostly from males, suggests that sexual maturity occurs around 8 to 9 meters (26 to 30 ft) in length, with females possibly maturing at a similar size or larger.[14][32][33][34] The maximum length of the species is uncertain due to a lack of detailed documentation of the largest reported individuals. Several whale sharks around 18 m (59 ft) in length have been reported.[8]