zh-CN

导览中的名字

Canis lupus lycaon és una subespècie del llop (Canis lupus)[2] present a Nord-amèrica: abans s'estenia a l'àrea compresa entre Florida i Minnesota, però avui dia es troba principalment al voltant dels Grans Llacs de Nord-amèrica, el sud-est d'Ontàrio i el sud-oest del Quebec.[3][4]

Presenta una gran varietat de colors (des del blanc al gris i des del marró al negre) i mostra sovint un morro de color marró vermellós. Acostuma a pesar entre 22,5 i 45 kg (el mascle adult mitjà en fa 34 i la femella 27). Fa entre 64 i 92 cm d'alçària.[4] A l'hivern es nodreix principalment d'animals grossos, com ara cérvols, ants i caribús. A altres èpoques de l'any hi afegeix rosegadors i peixos.[4]

El coit ocorre a final de l'hivern quan la parella alfa de la llopada s'aparellen, i, dos mesos després, la femella pareix una ventrada de 5–6 cadells. Són sords i cecs i pesen, si fa no fa, una lliura cadascun. Al cap de dues setmanes comencen a veure, mentre que el sentit de l'oïda no el tenen desenvolupat fins a la tercera setmana. Després de sis setmanes, ja són alimentats amb menjar sòlid regurgitat pels adults i, cap a finals de l'estiu, els cadells ja poden seguir la llopada en les seves activitats.[4]

Les activitats humanes són la seva principal amenaça. Va estar a punt de l'extinció als Estats Units a principi del segle XX i, avui dia, només sobreviu en el 3% de l'hàbitat original que ocupava en aquest país. Minnesota és l'únic estat on no es troba en perill d'extinció.[4]

Canis lupus lycaon és una subespècie del llop (Canis lupus) present a Nord-amèrica: abans s'estenia a l'àrea compresa entre Florida i Minnesota, però avui dia es troba principalment al voltant dels Grans Llacs de Nord-amèrica, el sud-est d'Ontàrio i el sud-oest del Quebec.

Presenta una gran varietat de colors (des del blanc al gris i des del marró al negre) i mostra sovint un morro de color marró vermellós. Acostuma a pesar entre 22,5 i 45 kg (el mascle adult mitjà en fa 34 i la femella 27). Fa entre 64 i 92 cm d'alçària. A l'hivern es nodreix principalment d'animals grossos, com ara cérvols, ants i caribús. A altres èpoques de l'any hi afegeix rosegadors i peixos.

El coit ocorre a final de l'hivern quan la parella alfa de la llopada s'aparellen, i, dos mesos després, la femella pareix una ventrada de 5–6 cadells. Són sords i cecs i pesen, si fa no fa, una lliura cadascun. Al cap de dues setmanes comencen a veure, mentre que el sentit de l'oïda no el tenen desenvolupat fins a la tercera setmana. Després de sis setmanes, ja són alimentats amb menjar sòlid regurgitat pels adults i, cap a finals de l'estiu, els cadells ja poden seguir la llopada en les seves activitats.

Les activitats humanes són la seva principal amenaça. Va estar a punt de l'extinció als Estats Units a principi del segle XX i, avui dia, només sobreviu en el 3% de l'hàbitat original que ocupava en aquest país. Minnesota és l'únic estat on no es troba en perill d'extinció.

Der Timberwolf (Canis lupus lycaon), auch Eastern Wolf, Great Lakes Wolf oder Algonquin Wolf, ist eine taxonomisch umstrittene Unterart des Wolfes. Seit der Monographie von Edward Alphonso Goldman wurde der Name für eine von 23 oder 24 Unterarten des Wolfes in Nordamerika verwendet, die den größten Teil des Ostens des Kontinents besiedelt haben soll. Später verwendete der Paläontologe und Wirbeltier-Taxonom Ronald M. Nowak den Namen für eine von acht Unterarten, die im Gebiet der Großen Seen heimisch sei. Spätere Autoren haben, vor allem gestützt auf widersprüchliche und kontrovers interpretierte genetische Daten, entweder die Existenz einer eigenständigen Art Canis lycaon, als einer von drei nordamerikanischen Caniden-Arten, postuliert, oder sie interpretierten die Populationen nur als eine Hybridzone zwischen dem (Grauen) Wolf Canis lupus und dem kleineren Kojoten (Canis latrans) und/oder dem Rotwolf (Canis rufus).

Umstritten ist bis heute nicht nur der Status als Art oder Unterart, sondern schon die Existenz einer eigenständigen Sippe (entweder noch existierend, oder zumindest in historischer Zeit vorhanden gewesen) und deren Verhältnis zum Rotwolf, der wahlweise ebenso als eigenständige Art oder als Unterart von entweder Canis lupus oder auch von Canis lycaon aufgefasst wurde und wird. Der Streit um den Status des Timberwolfs wird auch deshalb so erbittert geführt, weil neben rein wissenschaftlichen Interessen auch Fragen des Artenschutzes berührt sind.

Der Timberwolf ist eine mittelgroße Wolfssippe, die in ihrer Körpergröße intermediär zwischen dem (Grauen) Wolf Canis lupus des amerikanischen Westens und dem Kojoten steht. Sofern der Rotwolf vom Great-Lakes-Wolf unterschieden wird, ist der Rotwolf etwas größer als ein Kojote, aber kleiner als der Great-Lakes-Wolf. Lange für Verwirrung gesorgt haben Berichte über die Fellfarbe, die auf die ältesten wissenschaftlichen Berichte über Wölfe in Nordamerika zurückgehen. Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon berichtete 1761 von einem „loup noir“ aus Kanada, der in Europa ausgestellt wurde. William Bartram beschrieb 1791 einen „Lupus niger“ mit schwarzem Fell aus Florida, der später mit dem Rotwolf gleichgesetzt wurde. Johann Christian von Schrebers beschrieb 1775, gestützt auf dessen Abbildungen, Buffons „loup noir“ formal als Spezies Canis lycaon, deren Typlokalität damit Kanada ist, dieser wurde durch Gerrit Smith Miller nachträglich als Typus von Canis lycaon festgeschrieben. Spätere Beobachtungen in den Regionen konnten nur einzelne schwarze Wölfe dort bestätigen, die als Farbaberrationen (Schwärzlinge) gedeutet werden. Wölfe aus Wisconsin, die innerhalb des Areals der von Goldman definierten Unterart Canis lupus lycaon vorkamen, wurden morphologisch so gekennzeichnet (nach Johnston in Nowak 2009[1]): Körperlänge 1490 bis 1650 Millimeter, Gewicht 30 bis 45 Kilogramm, Schädellänge 230 bis 268 Millimeter, Ohren moderat groß und weniger auffallend als beim Kojote, moderat dichtes, recht grobes Fell, oberseits grau gefärbt, vom Nacken an schwärzlich überlaufen, Unterseite weißlich bis hellocker, Kopf ocker- bis zimtfarben überlaufen, Ohren gelbbraun, Beine außen gelbbraun bis zimtfarben, an den Vorderbeinen mit einer mehr oder weniger auffallenden schwarzen Linie. Kein wesentlicher Farbunterschied zwischen Sommer- und Winterpelz. Nach Goldman seien die Tiere im südöstlichen Ontario und südlichen Quebec etwas kleiner und etwas dunkler gefärbt als die weiter westlich lebenden. Nach neueren Maßen erreichen die Tiere aus dem Algonquin Provincial Park eine Körpermasse von durchschnittlich 24,5 (17 bis 23) Kilogramm im weiblichen und 27,7 (19,5 bis 36,7) Kilogramm im männlichen Geschlecht (zum Vergleich: Kojote: 10–18 kg, Grauer Wolf: 24 bis 60 kg).[2]

Seit dem Aufkommen leistungsfähiger genetischer Analysemethoden in den 2000er Jahren verlagerte sich die Diskussion um Status und Abgrenzung des Timberwolfs auf genetische Marker, da alle morphologischen Merkmale unklar und interpretationsabhängig sind. Die Probleme wurden hier dadurch verschärft, dass die östlichen Wölfe (Canis rufus und/oder Canis lycaon) im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert bis auf wenige, völlig isolierte Reliktpopulationen (darunter diejenige der Großen Seen) ausgerottet worden waren. Dies ermöglichte dem Kojoten, der ursprünglich im östlichen Nordamerika nicht einheimisch war, die Ausweitung seines Areals in diese Region. Durch experimentelle Befunde und Beobachtungen nachgewiesen, hybridisieren Kojoten und östliche Wölfe gelegentlich, vermutlich verschärft durch Mangel an Paarungspartnern in winzigen, verstreuten Reliktpopulationen. Heute nachweisbare genetische Übereinstimmungen zwischen östlichen Wölfen und Kojoten könnten auf solche junge Hybridisierungen zurückgehen, sie könnten auf gemeinsamen Allelen beruhen, die sowohl östliche Wölfe wie auch Kojoten von ihrem (gemeinsamen) Vorfahren geerbt hätten, oder auf jede Kombination dieser Faktoren. Im Jahr 2000 stellten dann Paul J. Wilson und Kollegen eine einflussreiche Studie vor[3], nach der die Wölfe des Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, als letzte weitgehend von Introgression unbeeinflusste Population des östlichen „grauen“ Wolfes gemeinsam mit dem Rotwolf eine eigenständige genetische Einheit bilden würden, die spezifisch verschieden sowohl vom Kojoten (seiner Schwesterart) wie auch von westlichen Grauen Wolf sei. Diese gemeinsame Art aus östlichem Wolf der Große-Seen-Region und Rotwolf nannten sie, aus Prioritätsgründen, Canis lycaon. Diesem Modell zufolge gäbe es also drei Canidenarten in Nordamerika. Die Resultate wurden in einer Folgestudie durch Christopher Kyle und Kollegen 2006 gestützt[4] (auch wenn die Autoren eine Hybridisierung sowohl mit Grauen Wölfen wie auch Kojoten bestätigen konnten). Andere Autoren, etwa eine Arbeitsgruppe um Bridgett M. von Holdt von der Princeton University[5] in einer Serie von Artikeln, widersprechen, ihrer Interpretation der Daten zufolge gäbe es nur zwei Arten in Nordamerika (den Grauen Wolf Canis lupus und den Kojoten Canis latrans) und diverse auf Hybridisierung zwischen diesen zurückgehende Populationen, zu denen auch der Rotwolf und der Timberwolf gehören würde. Auch anderen genetischen Studien zufolge, etwa Stephan Koblmüller und Kollegen[6] wäre der Great Lakes Wolf ein an die kleinere Beute in der Region angepasster Ökotyp des Grauen Wolfs, alle genetischen Besonderheiten gingen demnach auf Introgression von kürzlich zugewanderten Kojoten zurück. Dem wurde von verschiedenen Autoren aus Wilsons Gruppe widersprochen, der Streit ist bis heute nicht beigelegt.

Im Jahr 1967 wurde auf Grundlage des Endangered Species Protection Act „Canis lupus lycaon“, mit einem Verbreitungsgebiet von Minnesota bis ins östliche Kanada, unter Artenschutz gestellt. Einige Taxonomen postulierten, gestützt auf Fellfarbe und historische Berichte, bald darauf, die Tiere aus Minnesota wären in Wirklichkeit der ansonsten ausgerotteten Unterart Canis lupus nubilus (mit Verbreitung in den Great Plains) zugehörig, dies wurde später von Nowak anhand von Schädelmessungen unterstützt.[1] Ob die Wölfe in Wisconsin, Michigan und Minnesota Graue Wölfe (Canis lupus), Mischlinge zwischen Grauen Wölfen und den Great Lakes- oder Timberwölfen Kanadas und Grauen Wölfen sind und ob überhaupt diese Unterscheidung gerechtfertigt ist, wurde, gestützt auf die widersprüchlichen Fachmeinungen, unterschiedlich dargestellt. Problematisch ist dabei insbesondere, ob ein besonderer Schutz gerechtfertigt ist, wenn der Graue Wolf insgesamt nicht (mehr) als bestandsbedroht gilt.

In Kanada wird der „Algonquin Wolf“ (Canis lupus lycaon) als eine eigenständige Einheit im Rang einer Unterart des Grauen Wolfs anerkannt, der seit 2016 unter dem Endangered Species Act Ontarios besonderen Artenschutz genießt.[7]

Das im Adler- und Wolfspark Kasselburg in einem 10 ha großen Gelände untergebrachte Rudel Timberwölfe gilt als das größte Wolfsrudel Westeuropas.

Die Minnesota Timberwolves, eine Basketballmannschaft der nordamerikanischen NBA, sind nach dem Timberwolf benannt.

Der Spitzname der 104. Infanteriedivision der United States Army ist Timberwolf. Sie wurde im Zweiten Weltkrieg eingesetzt und war unter anderem an der kampflosen Einnahme von Halle an der Saale beteiligt.

Der Timberwolf (Canis lupus lycaon), auch Eastern Wolf, Great Lakes Wolf oder Algonquin Wolf, ist eine taxonomisch umstrittene Unterart des Wolfes. Seit der Monographie von Edward Alphonso Goldman wurde der Name für eine von 23 oder 24 Unterarten des Wolfes in Nordamerika verwendet, die den größten Teil des Ostens des Kontinents besiedelt haben soll. Später verwendete der Paläontologe und Wirbeltier-Taxonom Ronald M. Nowak den Namen für eine von acht Unterarten, die im Gebiet der Großen Seen heimisch sei. Spätere Autoren haben, vor allem gestützt auf widersprüchliche und kontrovers interpretierte genetische Daten, entweder die Existenz einer eigenständigen Art Canis lycaon, als einer von drei nordamerikanischen Caniden-Arten, postuliert, oder sie interpretierten die Populationen nur als eine Hybridzone zwischen dem (Grauen) Wolf Canis lupus und dem kleineren Kojoten (Canis latrans) und/oder dem Rotwolf (Canis rufus).

Umstritten ist bis heute nicht nur der Status als Art oder Unterart, sondern schon die Existenz einer eigenständigen Sippe (entweder noch existierend, oder zumindest in historischer Zeit vorhanden gewesen) und deren Verhältnis zum Rotwolf, der wahlweise ebenso als eigenständige Art oder als Unterart von entweder Canis lupus oder auch von Canis lycaon aufgefasst wurde und wird. Der Streit um den Status des Timberwolfs wird auch deshalb so erbittert geführt, weil neben rein wissenschaftlichen Interessen auch Fragen des Artenschutzes berührt sind.

Ο ανατολικός λύκος (Canis lupus lycaon)[1][2] είναι υποείδος του γκρίζου λύκου που είναι ιθαγενές στην περιοχή των Μεγάλων Λιμνών και τον νοτιοανατολικό Καναδά.[3] Το υποείδος είναι το αποκύημα της αρχαίας γενετικής ανάμειξης μεταξύ του γκρίζου λύκου και του κογιότ,[4][5] ωστόσο θεωρείται μοναδικό και ως εκ τούτου άξιο διατήρησης.[6] Υπάρχουν δύο μορφές, η μεγαλύτερη που αναφέρεται ως o λύκος των Μεγάλων Λιμνών και η μικρότερη όντας ο Αλγκονκίνος λύκος.[7][8] Η μορφολογία του ανατολικού λύκου βρίσκεται στο μέσο μεταξύ του βορειοδυτικού λύκου και του κογιότ.[3] Η γούνα είναι τυπικά σταχτιού γκριζωπού-καφέ χρώματος αναμεμειγμένου με κανελί. Η περιοχή του αυχένα, του ώμου και της ουράς είναι μια ανάμειξη μαύρου και γκρίζου, με τις πλευρές και το στήθος να είναι κεραμιδί ή κρεμ.[8] Ως επί το πλείστον θηρεύει το λευκόουρο ελάφι, αλλά περιστασιακά μπορεί να επιτίθεται σε άλκες και κάστορες.[9]

Ο ανατολικός λύκος (Canis lupus lycaon) είναι υποείδος του γκρίζου λύκου που είναι ιθαγενές στην περιοχή των Μεγάλων Λιμνών και τον νοτιοανατολικό Καναδά. Το υποείδος είναι το αποκύημα της αρχαίας γενετικής ανάμειξης μεταξύ του γκρίζου λύκου και του κογιότ, ωστόσο θεωρείται μοναδικό και ως εκ τούτου άξιο διατήρησης. Υπάρχουν δύο μορφές, η μεγαλύτερη που αναφέρεται ως o λύκος των Μεγάλων Λιμνών και η μικρότερη όντας ο Αλγκονκίνος λύκος. Η μορφολογία του ανατολικού λύκου βρίσκεται στο μέσο μεταξύ του βορειοδυτικού λύκου και του κογιότ. Η γούνα είναι τυπικά σταχτιού γκριζωπού-καφέ χρώματος αναμεμειγμένου με κανελί. Η περιοχή του αυχένα, του ώμου και της ουράς είναι μια ανάμειξη μαύρου και γκρίζου, με τις πλευρές και το στήθος να είναι κεραμιδί ή κρεμ. Ως επί το πλείστον θηρεύει το λευκόουρο ελάφι, αλλά περιστασιακά μπορεί να επιτίθεται σε άλκες και κάστορες.

The eastern wolf (Canis lycaon[5] or Canis lupus lycaon[6][7] or Canis rufus lycaon) also known as the timber wolf,[8] Algonquin wolf or eastern timber wolf,[9] is a canine of debated taxonomy native to the Great Lakes region and southeastern Canada. It is considered to be either a unique subspecies of gray wolf or red wolf or a separate species from both.[10] Many studies have found the eastern wolf to be the product of ancient and recent genetic admixture between the gray wolf and the coyote,[11][12] while other studies have found some or all populations of the eastern wolf, as well as coyotes, originally separated from a common ancestor with the wolf over 1 million years ago and that these populations of the eastern wolf may be the same species as or a closely related species to the red wolf (Canis lupus rufus or Canis rufus) of the Southeastern United States.[13][14][10] Regardless of its status, it is regarded as unique and therefore worthy of conservation[15] with Canada citing the population in eastern Canada (also known as the "Algonquin wolf") as being the eastern wolf population subject to protection.[16]

There are two forms, the larger being referred to as the Great Lakes wolf, which is generally found in Minnesota, Wisconsin, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, southeastern Manitoba and northern Ontario, and the smaller being the Algonquin wolf, which inhabits eastern Canada, specifically central and eastern Ontario and southwestern Quebec, with some overlapping and mixing of the two types in the southern portions of northeastern and northwestern Ontario.[17][18][19] The eastern wolf's morphology is midway between that of the gray wolf and the coyote.[10] The fur is typically of a grizzled grayish-brown color mixed with cinnamon. The nape, shoulder and tail region are a mix of black and gray, with the flanks and chest being rufous or creamy.[18] It primarily preys on white-tailed deer, but may occasionally hunt moose and beavers.[20]

In the third edition of Mammal Species of the World published in 2005, the mammalogist W. Christopher Wozencraft listed the eastern wolf as a gray wolf subspecies,[6] which supports its earlier classification based on morphology in three studies.[21][22][23] This taxonomic classification has since been debated, with proposals based on DNA analyses that includes a gray wolf ecotype,[24] a gray wolf with genetic introgression from the coyote,[17] a gray wolf/coyote hybrid,[25] a gray wolf/red wolf hybrid,[23] the same species as the red wolf,[13] or a separate species (Canis lycaon) closely related to the red wolf.[13] Commencing in 2016, two studies using whole genome sequencing indicate that North American gray wolves and wolf-like canids were the result of ancient and complex gray wolf and coyote mixing,[11][12] with the Great Lakes wolf possessing 25% coyote ancestry and the Algonquin wolf possessing 40% coyote ancestry.[12]

In the US, a bill is before Congress to remove protections under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 for the gray wolf populations located in the western Great Lakes region.[26] In Canada, the eastern wolf is listed as Canis lupus lycaon under the Species At Risk Act 2002, Schedule 1 - List of Wildlife at Risk.[16] In 2015, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada recognized the eastern wolf in central and eastern Ontario and southwestern Quebec as Canis cf. lycaon (Canis species believed to be lycaon)[27] and a threatened species worthy of conservation.[28] The main threat to this wolf is human hunting and trapping outside of the protected areas, which leads to genetic introgression with the eastern coyote due to a lack of mates. Further human development immediately outside of the protected areas and the negative public perception of wolves are expected to inhibit any further expansion of their range.[28] In 2016, the Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario recognized the Algonquin wolf as a Canis sp. (Canis species) differentiated from the hybrid Great Lakes wolves which it found were the result of "hybridization and backcrossing among Eastern Wolf (Canis lycaon) (aka C. lupus lycaon), Gray Wolf (C. lupus), and Coyote (C. latrans)".[29]

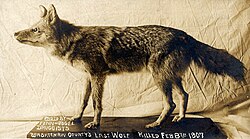

The first published name of a taxon belonging to the genus Canis from North America is Canis lycaon. It was published in 1775 by the German naturalist Johann Schreber, who had based it on the earlier description and illustration of one specimen that was thought to have been captured near Quebec. It was later reclassified as a subspecies of gray wolf by Edward Goldman.[30]

In the third edition of Mammal Species of the World published in 2005, the mammalogist W. Christopher Wozencraft listed the eastern wolf as a gray wolf subspecies,[6] which supports its earlier classification based on morphology in three studies.[21][22][23] This taxonomic classification has since been debated.

In 2021, the American Society of Mammalogists considered the eastern wolf as its own species (Canis lycaon).[5]

When European settlers first arrived to North America, the coyote's range was limited to the western half of the continent. They existed in the arid areas and across the open plains, including the prairie regions of the midwestern states. Early explorers found some in Indiana and Wisconsin. From the mid-1800s coyotes began expanding beyond their original range.[31]

The taxonomic debate regarding North American wolves can be summarised as follows:

There are two prevailing evolutionary models for North American Canis:

- (i) a two-species model

- that identifies grey wolves (C. lupus) and (western) coyotes (Canis latrans) as distinct species that gave rise to various hybrids, including the Great Lakes-boreal wolf (also known as Great Lakes wolf), the eastern coyote (also known as coywolf / brush wolf / tweed wolf), the red wolf and the eastern wolf;

or

- (ii) a three-species model

- that identifies the grey wolf, western coyote, and eastern wolf (C. lycaon) as distinct species, where Great Lakes-boreal wolves are the product of grey wolf × eastern wolf hybridization, eastern coyotes are the result of eastern wolf × western coyote hybridization, and red wolves are considered historically the same species as the eastern wolf, although their contemporary genetic signature has diverged owing to a bottleneck associated with captive breeding.[32]

The evolutionary biologist Robert K. Wayne, whose team is involved in an ongoing scientific debate with the team led by Linda K. Rutledge, describes the difference between these two evolutionary models: "In a way, it is all semantics. They call it a species, we call it an ecotype."[10]

Some of the earliest Canis specimens were discovered at Cripple Creek Sump, Fairbanks, Alaska, in strata dated 810,000 years old. The dental measurements of the specimens clearly match historical Canis lycaon specimens from Minnesota.[33]

Mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) passes along the maternal line and can date back thousands of years.[10]

In 1991, a study of the mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) sequences of wolves and coyotes from across North America found that the wolves of the Minnesota, Ontario and Quebec regions possessed coyote genotypes. The study proposes that dispersing male gray wolves were mating with coyote females in deforested areas bordering wolf territory. The distribution of coyote genotypes within wolves matched the phenotypic differences between these wolves found in an earlier study, with the larger Great Lakes wolf found in Minnesota, the smaller Algonquin (Provincial Park) type found in central Ontario, and the smallest and more coyote-like tweed wolf or eastern coyote type occupying sections of southeastern Ontario and southern Quebec.[17]

In 2000, a study looked at red wolves and eastern wolves from both eastern Canada and Minnesota. The study agreed that these two wolves readily hybridize with the coyote. The study used 8 microsatellites (genetic markers taken from across the genome of a specimen). The phylogenetic tree produced from the genetic sequences showed a close relationship among the red wolves and the eastern wolves from Algonquin Park, southern Quebec, and Minnesota such that they all clustered together. These then clustered next closer with the coyote and away from the gray wolf. A further analysis using mDNA sequences indicated the presence of coyote in both of these two wolves, and that these two wolves had diverged from the coyote 150,000–300,000 years ago. No gray wolf sequences were detected in the samples. The study proposed that these findings are inconsistent with the two wolves being subspecies of the gray wolf, that red wolves and eastern wolves (eastern Canadian and Minnesota) evolved in North America after having diverged from the coyote, and therefore they are more likely to hybridize with coyotes.[13]

In 2009, a study of eastern Canadian wolves – which was referred to as the "Great Lakes" wolf in this study – using microsatellites, mDNA, and the paternally-inherited yDNA markers found that the eastern Canadian wolf was a unique ecotype of the gray wolf that had undergone recent hybridization with other gray wolves and coyotes. It could find no evidence to support the findings of the earlier 2000 study regarding the eastern Canadian wolf. The study did not include the red wolf.[24] This study was quickly rebutted on the grounds that it had misinterpreted the findings of earlier studies that it relied upon, nor did it provide a definition for a number of the terms that it used, such as "ecotype".[34]

In 2011, a study compared the genetic sequences of 48,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (mutations) taken from the genomes of canids from around the world. The comparison indicated that the red wolf was about 76% coyote and 24% gray wolf with hybridization having occurred 287–430 years ago. The eastern wolf – which was referred to as the "Great Lakes" wolf in this study – was 58% gray wolf and 42% coyote with hybridization having occurred 546–963 years ago. The study rejected the theory of a common ancestry for the red and eastern wolves.[25][10] However the next year, a study reviewed a subset of the 2011 study's Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data and proposed that its methodology had skewed the results and that the eastern wolf is not a hybrid but a separate species.[14][10] The 2012 study proposed that there are 3 true canis species in North America - the gray wolf, the western coyote, and red wolf/eastern wolf with the eastern wolf represented by the Algonquin wolf, with the Great Lakes wolf being a hydrid of the eastern wolf and the gray wolf, and the eastern coyote being a hybrid of the western coyote and the eastern (Algonquin) wolf.[14]

Also in 2011, a scientific literature review was undertaken to help assess the taxonomy of North American wolves. One of the findings proposed was that the eastern wolf, whose range includes eastern Canada and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan plus Wisconsin and Minnesota is supported as a separate species by morphological and genetic data. Genetic data supports a close relationship between the eastern and red wolves, but not close enough to support these as one species. It was "likely" that these were the separate descendants of a common ancestor shared with coyotes. This review was published in 2012.[30]

Another study of both mDNA and yDNA in wolves and coyotes by the same authors indicates that the eastern wolf is genetically divergent from the gray wolf and is a North American evolved species with a long-standing history. The study could not dismiss the possibility of the eastern wolf having evolved from an ancient hybridization of gray wolf and coyote in the Late Pleistocene or Early Holocene.[35] Another study by the same authors found that eastern wolf mDNA genetic diversity had been lost after their culling in the early 1960s, leading to the invasion of coyotes into their territory and introgression of coyote mDNA.[36]

In 2014, the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis was invited by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service to provide an independent review of its proposed rule relating to gray wolves. The Center's panel findings were that the proposed rule was heavily dependent upon the analysis contained in a scientific literature review conducted in 2011 (Chambers et al.), that this work was not universally accepted and that the issue was "not settled", and that the rule does not represent the "best available science".[37] Also in 2014, an experiment to hybridize a captive western gray wolf and a captive western coyote was successful, and therefore possible. The study did not assess the likelihood of such hybridization in the wild.[38]

In 2015, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada changed its designation of the eastern wolf from Canis lupus lycaon to Canis cf. lycaon (Canis species believed to be lycaon)[27] and a species at risk.[28]

Later that year, a study compared the DNA sequences using 127,000 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (mutations) of wolves and coyotes, but did not include red wolves and used Algonquin wolves as the representative eastern wolf, not wolves from the western Great Lakes states (usually referred to as Great Lakes wolves). The study indicated that Algonquin wolves were a distinct genomic cluster, even distinct from the Great Lakes states' wolves, which it found were actually hybrids of the gray wolf and the Algonquin wolf. The study's results did not exclude a possibility that the Great Lakes states' wolf (the gray wolf x eastern wolf hybrid (C. l. lycaon)) historically inhabited southern Ontario, southern Quebec and the northeastern United States alongside the Algonquin wolf, as there is evidence to suggest both inhabited those areas.[32]

In 2016, a study of mDNA once again indicated the Eastern wolf as a coyote–wolf hybrid.[39]

In 2018, a study looked at the y-chromosome male lineage of canines. The unexpected finding was that the one Great Lakes wolf specimen included in this study showed a high degree of genetic divergence. Previous studies propose the Great Lakes wolf to be an ancient ecotype of the gray wolf that had experienced genetic introgression from other types of gray wolves and coyotes. The study called for further research into the Y-chromosomes of coyotes and wolves to ascertain if this is where this unique genetic male lineage may have originated from.[40]

In 2016, a whole-genome DNA study proposed, based on the assumptions made, that all of the North American wolves and coyotes diverged from a common ancestor less than 6,000–117,000 years ago, including the coyote diverging from Eurasian wolf about 51,000 years ago (which matches other studies indicating that the extant wolf came into being around this time), the red wolf diverging from the coyote between 55,000–117,000 years ago, and the eastern wolf (Great Lakes region and Algonquin) wolf diverging from the coyote 27,000–32,000 years ago, and asserts that these do not qualify as an ancient divergences that justify them being considered unique species.[11]

The study also indicated that all North America wolves have a significant amount of coyote ancestry and all coyotes some degree of wolf ancestry, and that the red wolf and eastern wolf are highly admixed with different proportions of gray wolf and coyote ancestry. The study found that coyote ancestry was highest in red wolves from the southeast of the United States and lowest among the Great Lakes wolves.[11]

The study also determined how unique each type of canids alleles were compared to Eurasian wolves, all of which had no coyote ancestry. It found the following proportion of unique alleles: coyotes 5.13% unique; red wolf 4.41%; Algonquin wolves 3.82%; Great Lakes wolves 3.61%; and gray wolves 3.3%. They asserted that the amount of unique alleles in all wolves was lower than expected and does not support an ancient (greater than 250,000 years) unique ancestry for any of the species.[11]

The authors contended that the proportion of unique alleles and ratio of wolf / coyote ancestry findings matched the south to north disappearance of the wolf due to European colonization since the 18th century and the resulting loss of habitat. Bounties led to the extirpation of wolves initially in the southeast, and as the wolf population declined wolf–coyote admixture increased. Later, this process occurred in the Great Lakes region and then eastern Canada with the influx of coyotes replacing wolves, followed by the expansion of coyotes and their hybrids. The Great Lakes and Algonquin wolves largely reflect lineages that have descendants in the modern wolf and coyote populations, but also reflect a distinct gray wolf ecotype which may have descendants in the modern wolf populations.[11]

As a result of these findings, the American Society of Mammalogists recognizes Canis lycaon as its own species.[5]

The proposed timing of the wolf/coyote divergence conflicts with the finding of a coyote-like specimen in strata dated to 1 million years before present.[41]

In 2017 a group of canid researchers challenged the 2016 whole-genome DNA study's finding that the red wolf and the eastern wolf were the result of recent coyote–gray wolf hybridization. The group asserts the three-year generation time used to calculate the divergence periods between different species was lower than empirical estimates of 4.7 years. The group also found deficiencies in the previous study's selection of specimens (two representative coyotes were from areas where recent coyote and gray wolf mixing with eastern wolves is known to have occurred), the lack of certainty in the ancestry of the selected Algonquin wolves, and the grouping of Great Lakes and Algonquin wolves together as eastern wolves, despite opposing genetic evidence. As well, they asserted the 2016 study ignored the fact that there is no evidence of hybridization between coyotes and gray wolves.[42]

The group also questioned the conclusions of genetic differentiation analysis in the study stating that results showing Great Lakes, Algonquin and red wolves, plus eastern coyotes differentiated from gray and Eurasian wolves were actually more consistent with an ancient hybridization or a distinct cladogenic origin for the red and Algonquin wolves than of a recent hybrid origin. The group further asserted that the levels of unique alleles for red and Algonquin wolves found the 2017 study were high enough to reveal a high degree of evolutionary distinctness. Therefore, the group argues that both the red wolf and the eastern wolf remain genetically distinct North American taxa.[42] This was rebutted by the authors of the earlier study.[43]

Genetic studies relating to wolves or dogs have inferred phylogenetic relationships based on the only reference genome available: that of the dog breed called the Boxer. In 2017, the first reference genome of the wolf Canis lupus lupus was mapped to aid future research.[44] In 2018, a study looked at the genomic structure and admixture of North American wolves, wolf-like canids, and coyotes using specimens from across their entire range that mapped the largest dataset of nuclear genome sequences and compared these against the wolf reference genome. The study supports the findings of previous studies that North American gray wolves and wolf-like canids were the result of complex gray wolf and coyote mixing. A polar wolf from Greenland and a coyote from Mexico represented the purest specimens. The coyotes from Alaska, California, Alabama, and Quebec show almost no wolf ancestry. Coyotes from Missouri, Illinois, and Florida exhibit 5–10% wolf ancestry. There was 40%:60% wolf to coyote ancestry in red wolves, 60%:40% in eastern wolves, and 75%:25% in the Great Lakes wolves. There was 10% coyote ancestry in Mexican wolves, 5% in Pacific Coast and Yellowstone wolves, and less than 3% in Canadian archipelago wolves.[12]

The study indicates that the genomic ancestry of red, eastern and Great Lakes wolves were the result of admixture between modern gray wolves and modern coyotes. This was then followed by development into local populations. Individuals within each group showed consistent levels of coyote to wolf inheritance, indicating that this was the result of relatively ancient admixture. The eastern wolf as found in Algonquin Provincial Park is genetically closely related to the Great Lakes wolf as found in Minnesota and Isle Royale National Park in Michigan. If a third canid had been involved in the admixture of the North American wolf-like canids, then its genetic signature would have been found in coyotes and wolves, which it has not.[12]

Later in 2018, a study based on a much smaller sample of 65,000 SNPs found that although the eastern wolf carries regional gray wolf and coyote alleles (gene variants), it also exhibits some alleles that are unique and therefore worthy of conservation.[15]

The software that is currently used to conduct whole genome analysis for evidence of hybridization does not distinguish between past and present hybridization. In 2021, an mDNA analysis of modern and extinct North American wolf-like canines indicates that the extinct Late Pleistocene Beringian wolf was the ancestor of the southern wolf clade, which includes the Mexican wolf and the Great Plains wolf. The Mexican wolf is the most ancestral of the gray wolves that live in North America today. The modern coyote appeared around 10,000 years ago. The most genetically basal coyote mDNA clade pre-dates the Last Glacial Maximum and is a haplotype that can only be found in the Eastern wolf. This implies that the large, wolf-like Pleistocene coyote was the ancestor of the Eastern wolf. Further, another ancient haplotype detected in the Eastern wolf can be found only in the Mexican wolf. The authors propose that Pleistocene coyote and Beringian wolf admixture led to the Eastern wolf long before the arrival of the modern coyote and the modern wolf.[45]

Charles Darwin was told that there were two types of wolf living in the Catskill Mountains, one being a lightly-built, greyhound-like animal that pursued deer, and the other being a bulkier, shorter-legged wolf.[46][47] The eastern wolf's fur is typically of a grizzled grayish-brown coloration, mixed with cinnamon. The flanks and chest are rufous or creamy, while the nape, shoulder and tail region are a mix of black and gray. Unlike gray wolves, eastern wolves rarely produce melanistic individuals.[18] The first documented all-black eastern wolf was found to have been an eastern wolf–gray wolf hybrid.[48] Like the red wolf, the eastern wolf is intermediate in size between the coyote and gray wolf, with females weighing 23.9 kilograms (53 lb) on average and males 30.3 kilograms (67 lb). Like the gray wolf, its average lifespan is 3–4 years, with a maximum of 15 years.[20] Their physical sizes that sets them intermediate between gray wolves and coyotes are actually believed to be more related to their adaptations to an environment with predominately medium-sized prey (similar to the case with the Mexican wolf in the southwestern US) rather than their close relationship to red wolves and coyotes.[24]

The eastern wolf primarily targets small to medium-sized prey items like white-tailed deer and beavers, unlike the gray wolf, which can effectively hunt large ungulates like caribou, elk, moose and bison.[48] Despite being carnivores, packs in Voyageurs National Park forage for blueberries in much of July and August, when the berries are in season. Packs carefully avoid each other; only lone wolves sometimes enter other packs' territories.[49] The average territory ranges between 110–185 km²,[20] and the earliest age of dispersal for young eastern wolves is 15 weeks, much earlier than gray wolves.[48]

The past range of the eastern wolf included southern Quebec, most of Ontario, the Great Lakes states, New York State and New England.[48] Today, the Great Lakes wolf is generally found in the northern halves of Minnesota and Wisconsin, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan,[50] southeastern Manitoba and northern Ontario,[19] and the Algonquin wolf inhabits central and eastern Ontario as well as southwestern Quebec north of the St. Lawrence River.[19][29] Algonquin wolves are particularly concentrated in Algonquin Provincial Park and other nearby protected areas, such as Killarney, Kawartha Highlands and Queen Elizabeth II Wildlands Provincial Parks and recent surveys also reveal small numbers of Algonquin wolves in the southern areas of northeastern Ontario and northwestern Ontario as far west as the Lake of the Woods near the border with Manitoba, where there is some mixing with Great Lakes wolves, and into southcentral Ontario, where there is some mixing with eastern coyotes.[19] There are some reports of eastern wolf sightings and of wolves being shot by hunters in Quebec south of the St. Lawrence River, New Brunswick, New York State, northern Vermont and Maine.[50][51][52][53] For example, DNA results of a canid killed near Cherry Valley, New York in 2021 initially pointed to it being an eastern coyote, but a recent statement by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) confirms the animal was a wolf, with most of its ancestry matching wolves in Michigan; the DEC also has not confirmed or denied a breeding population within the state. Certain proponents of wolf recolonization state that wolves are already established in New York and New England, and have naturally dispersed from Canada by crossing the frozen St. Lawrence River.[54]

Mitochondrial DNA indicates that before the arrival of Europeans, eastern wolves may have numbered at 64,500 to 90,200 individuals.[36] In 1942 it was believed that, before European settlement, the wolf had ranged throughout the wooded and open areas of eastern North America from what is now southern Quebec westward to the Great Plains and towards the Southeastern Woodlands (the southern extent was uncertain, but was believed to around what is now Kentucky, Tennessee and North Carolina).[55] The region's indigenous human populations did not fear eastern wolves, though they did occasionally catch them in traps, and their bones occur in native shell heaps.[55]

Early European settlers often kept their livestock on eastern wolf-free outer islands, though animals kept in pasture on the mainland were vulnerable, to the point that a campaign against eastern wolves was launched in the early years of the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies, in which both settlers and natives participated. A bounty system was put into effect, offering higher rewards for adult wolves, with their heads exposed on hooks in meetinghouses. Nevertheless, wolves were still plentiful enough in New England in the early 18th century to warrant the settlers of Cape Cod discussing the building of a high fence between Sandwich and Wareham to keep them out of grazing lands. The scheme failed, though the settlers continued to utilize wolf pits, a wolf trapping technique learned from the region's indigenous peoples. Eastern wolf numbers declined noticeably shortly before and after the American Revolution, particularly in Connecticut, where the wolf bounty was repealed in 1774. Eastern wolf numbers, however, were still high enough to cause concern in the more sparsely populated areas of southern New Hampshire and Maine, with wolf hunting becoming a regular occupation among settlers and natives alike. By the early 19th century, few eastern wolves remained in southern New Hampshire and Vermont.[55]

Prior to the establishment of Algonquin Provincial Park in 1893, the eastern wolf was common in central Ontario and the Algonquin Highlands. It continued to persist throughout the late 1800s, despite extensive logging and efforts by park rangers to eliminate it, largely due to the sustaining influence of plentiful prey items like deer and beaver. By the mid-1900s, there were as many as 55 eastern wolf packs in the park,[56] with an average of 49 wolves being killed annually between 1909–1958, until they were given official protection by the Ontario government in 1959, by which time the eastern wolf population in and around the park had been reduced to 500–1,000 individuals.[36][56] Nevertheless, between 1964–1965, 36% of the park's wolf population was culled by researchers trying to understand the reproduction and age structure of the population. This cull coincided with the expansion of coyotes into the park, and lead to an increase in eastern wolf–coyote hybridization.[36] Introgression of gray wolf genes into the eastern wolf population also occurred across northern and eastern Ontario, into Manitoba and Quebec, as well as into the western Great Lakes states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan.[48] Despite protection within the park boundaries, there was a population decline in the east side of the park between 1987–1999, with an estimated number of 30 packs by 2000. This decline exceeded annual recruitment, and was attributed to human-caused mortality, which mostly occurred when dispersing animals left the park in search of deer during the winter months, and when pack ranges overlapped with park boundaries.[56] By 2001, protection was extended to eastern wolves occurring in the outskirts of the park. By 2012, the genetic composition of the park's eastern wolves was roughly restored to what it was in the mid-1960s than in the 1980s–1990s, when the majority of wolves had large amounts of coyote DNA.[36]

In 2013, an experiment which produced hybrids of coyotes and northwestern gray wolves in captivity using artificial insemination contributed more information to the controversy surrounding the eastern wolf's taxonomy. The purpose of this project was to determine whether the female western coyotes are capable of bearing hybrid western gray wolf-coyote pups, as well as to test the hybrid theory surrounding the origin of the eastern wolves. The resulting six hybrids produced in this captive artificial breeding were later transferred to the Wildlife Science Center of Forest Lake in Minnesota, where their behaviors were studied.[38]

The wolf is prominently portrayed in Algonquin mythology, where it is referred to as ma-hei-gan or nah-poo-tee in the Algonquian languages. It is the spirit brother of the Algonquian folk hero Nanabozho, and assisted him in several of his adventures, including thwarting the plots of the malicious anamakqui spirits and assisting him in recreating the world after a worldwide flood.[57]

Since the discovery in 1963 that eastern wolves answered human imitations of their howls, Algonquin Provincial Park began its Public Wolf Howls attraction, where as many as 2,500 visitors are led on expeditions into areas where eastern wolves were sighted the night before and listen to them answering the park staff's imitation howls. By 2000, 85 Public Wolf Howls had been held, with over 110,000 people having participated. The park considers the attraction as the cornerstone of its wolf education program and credits it with changing public attitudes towards wolves in Ontario.[56]

Since the early 1970s, there have been several incidents of bold or aggressive behavior towards humans in Algonquin Provincial Park. Between 1987 and 1996, there were four instances of wolves biting people. The most serious case occurred in 1998 when a male wolf that had been long noted to be unafraid of humans stalked a couple walking their four-year-old daughter in September that year, losing interest when the family took refuge in a trailer. Two days later, the wolf attacked a 19-month-old boy, causing several puncture wounds on his chest and back before being driven off by campers. After the animal was killed later that day, it was found to not be rabid.[58]

The eastern wolf (Canis lycaon or Canis lupus lycaon or Canis rufus lycaon) also known as the timber wolf, Algonquin wolf or eastern timber wolf, is a canine of debated taxonomy native to the Great Lakes region and southeastern Canada. It is considered to be either a unique subspecies of gray wolf or red wolf or a separate species from both. Many studies have found the eastern wolf to be the product of ancient and recent genetic admixture between the gray wolf and the coyote, while other studies have found some or all populations of the eastern wolf, as well as coyotes, originally separated from a common ancestor with the wolf over 1 million years ago and that these populations of the eastern wolf may be the same species as or a closely related species to the red wolf (Canis lupus rufus or Canis rufus) of the Southeastern United States. Regardless of its status, it is regarded as unique and therefore worthy of conservation with Canada citing the population in eastern Canada (also known as the "Algonquin wolf") as being the eastern wolf population subject to protection.

There are two forms, the larger being referred to as the Great Lakes wolf, which is generally found in Minnesota, Wisconsin, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, southeastern Manitoba and northern Ontario, and the smaller being the Algonquin wolf, which inhabits eastern Canada, specifically central and eastern Ontario and southwestern Quebec, with some overlapping and mixing of the two types in the southern portions of northeastern and northwestern Ontario. The eastern wolf's morphology is midway between that of the gray wolf and the coyote. The fur is typically of a grizzled grayish-brown color mixed with cinnamon. The nape, shoulder and tail region are a mix of black and gray, with the flanks and chest being rufous or creamy. It primarily preys on white-tailed deer, but may occasionally hunt moose and beavers.

In the third edition of Mammal Species of the World published in 2005, the mammalogist W. Christopher Wozencraft listed the eastern wolf as a gray wolf subspecies, which supports its earlier classification based on morphology in three studies. This taxonomic classification has since been debated, with proposals based on DNA analyses that includes a gray wolf ecotype, a gray wolf with genetic introgression from the coyote, a gray wolf/coyote hybrid, a gray wolf/red wolf hybrid, the same species as the red wolf, or a separate species (Canis lycaon) closely related to the red wolf. Commencing in 2016, two studies using whole genome sequencing indicate that North American gray wolves and wolf-like canids were the result of ancient and complex gray wolf and coyote mixing, with the Great Lakes wolf possessing 25% coyote ancestry and the Algonquin wolf possessing 40% coyote ancestry.

In the US, a bill is before Congress to remove protections under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 for the gray wolf populations located in the western Great Lakes region. In Canada, the eastern wolf is listed as Canis lupus lycaon under the Species At Risk Act 2002, Schedule 1 - List of Wildlife at Risk. In 2015, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada recognized the eastern wolf in central and eastern Ontario and southwestern Quebec as Canis cf. lycaon (Canis species believed to be lycaon) and a threatened species worthy of conservation. The main threat to this wolf is human hunting and trapping outside of the protected areas, which leads to genetic introgression with the eastern coyote due to a lack of mates. Further human development immediately outside of the protected areas and the negative public perception of wolves are expected to inhibit any further expansion of their range. In 2016, the Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario recognized the Algonquin wolf as a Canis sp. (Canis species) differentiated from the hybrid Great Lakes wolves which it found were the result of "hybridization and backcrossing among Eastern Wolf (Canis lycaon) (aka C. lupus lycaon), Gray Wolf (C. lupus), and Coyote (C. latrans)".

Canis lycaon es una posible subespecie de lobo o una especie de cánido diferente al lobo gris, referido a veces en español como lobo rojo canadiense o sencillamente licaón.[cita requerida] Fue elevada a categoría de especie en 1999 por White y Wilson, basándose en estudios genéticos. Habita el sureste de Canadá y su nombre en inglés es eastern canadian wolf. Estos autores indican que está emparentada con el lobo rojo (Canis rufus), otra especie de dudosa validez, y que es más próxima al coyote que al lobo común. Esta afirmación no goza del adecuado consenso de los expertos, pero hay cierta tendencia a considerar que Canis rufus y Canis lycaon son la misma especie, siendo el nombre latino correcto Canis lycaon. De ser este el caso, se mantendría en español el nombre vulgar "lobo rojo" para ambas.

Las opiniones posteriores se reparten entre aceptar Canis lycaon como especie exclusiva del sureste de Canadá, considerar que Canis lycaon engloba a los lobos rojos autóctonos del sureste de Norteamérica (lycaon más rufus), que se trata de híbridos entre lobo común y lobo rojo, o que, de acuerdo a la visión clásica, es una subespecie de lobo común Canis lupus lycaon.[1]

De confirmarse que Canis lycaon es conespecfíco con Canis rufus, los lobos del sureste de Canadá podrían utilizarse en los programas de reintroducción de lobo rojo en Estados Unidos. Además, si fuera el caso, habría que revisar el estado de conservación de esta última especie, que no sería tan crítico.

Canis lycaon es una posible subespecie de lobo o una especie de cánido diferente al lobo gris, referido a veces en español como lobo rojo canadiense o sencillamente licaón.[cita requerida] Fue elevada a categoría de especie en 1999 por White y Wilson, basándose en estudios genéticos. Habita el sureste de Canadá y su nombre en inglés es eastern canadian wolf. Estos autores indican que está emparentada con el lobo rojo (Canis rufus), otra especie de dudosa validez, y que es más próxima al coyote que al lobo común. Esta afirmación no goza del adecuado consenso de los expertos, pero hay cierta tendencia a considerar que Canis rufus y Canis lycaon son la misma especie, siendo el nombre latino correcto Canis lycaon. De ser este el caso, se mantendría en español el nombre vulgar "lobo rojo" para ambas.

Las opiniones posteriores se reparten entre aceptar Canis lycaon como especie exclusiva del sureste de Canadá, considerar que Canis lycaon engloba a los lobos rojos autóctonos del sureste de Norteamérica (lycaon más rufus), que se trata de híbridos entre lobo común y lobo rojo, o que, de acuerdo a la visión clásica, es una subespecie de lobo común Canis lupus lycaon.

De confirmarse que Canis lycaon es conespecfíco con Canis rufus, los lobos del sureste de Canadá podrían utilizarse en los programas de reintroducción de lobo rojo en Estados Unidos. Además, si fuera el caso, habría que revisar el estado de conservación de esta última especie, que no sería tan crítico.

Itäkanadansusi tunnetaan useilla erinimillä; metsäsusi, algonquininsusi, Eastern North America Timber Wolf (Canis lupus lycaon).

Tätä lajia on pidetty suden alalajina, mutta se ehkä onkin oma lajinsa (Canis lycaon). Näin se olisi neljäs "susi" Pohjois-Amerikassa pienimmän eli kojootin (Canis latrans) keskikokoisen eli punasuden (Canis rufus) ja ison suden eli harmaasuden (Canis lupus) kanssa.

Itäkanadansusia on pääasiassa vain Algonquinin puistossa Kanadan ja USAn rajalla.

Susien istuttamista muualle Yhdysvaltojen koillissosaan on harkittu.[2]

Itäkanadansusi on pienempi kuin harmaasusi ja sillä on harmaanpunertava turkki, jossa on mustaa selässä ja kyljissä. Sen iho on harmaan rusehtava. Korvien takana on punertavaa väriä, tämä on merkki sen sukulaisuudesta punasuden kanssa. Täysin mustia tai valkoisia yksilöitä ei ole tavattu. Itäkanadansusi on myös sirompi kuin harmaasusi ja sillä on myös enemmän kojoottimaisia piirteitä. Tämä on mahdollista sillä sudet ja kojootit usein risteytyvät keskenään.

Itäkanadansuden paino on 25-30kg, eli huomattavasti pienempi kuin harmaasusi. Alalajien määrittäminen on ollu vaikeaa sillä susi, punasusi ja kojootti risteytyvät helposti keskenään. Näin luonnostaan tavataan suuri kirjo erilaisia ristisiitoksia eli hybridejä ja tämän lisäksi kullekin lajille on suuri määrä alalajeja, jotka jo ulkonäöltään eroavat huomattavasti toisistaan.

Itäkanadansusi saalistaa valkohäntäpeuroja, hirviä, jäniseläimiä ja jyrsijöitä mukaan lukien majavia, piisameja ja hiiriä. Sudet metsästävät useimmin majavia kesällä ja talvella valkohäntäpeuroja.

Itäkanadansusi tunnetaan useilla erinimillä; metsäsusi, algonquininsusi, Eastern North America Timber Wolf (Canis lupus lycaon).

Canis lycaon, Canis lupus lycaon

Le loup de l'Est (Canis lycaon) est un mammifère carnivore de la famille des Canidae que l'on trouve en Amérique du Nord. Les études génétiques réalisées au XXIe siècle confirment qu'il s'agit bien d'une espèce du Nouveau Monde à part entière et non pas d'une sous-espèce (Canis lupus lycaon) du Loup gris (Canis lupus) comme on l'a accepté un temps. En français, de nombreux noms ont été proposés pour le désigner (loup du Canada, loup gris de l'Est, loup rouge de l'Est, loup des bois de l'est[2]...) mais c'est l'appellation Loup de l'Est qui est la plus courante[3].

Les populations de ce loup se rencontrent principalement au Canada, en particulier dans l'aire protégée du parc provincial Algonquin[4].

Il ne faut pas confondre Canis lycaon avec une autre espèce de Canidés bien différente, le lycaon (Lycaon pictus).

La communauté scientifique a changé plusieurs fois d'avis au cours de l'histoire.

Les premières classifications réalisées ont considéré ce loup comme étant une espèce à part entière (Canis lycaon), distincte du Loup gris (Canis lupus)[2]. Ensuite, en se basant sur les études morphologiques, on a émis l'hypothèse que le Loup de l'Est serait une sous-espèce de ce dernier, que l'on a désignée alors comme Canis lupus lycaon. D'autres encore considèrent qu'il s'agit plutôt du résultat de croisements entre le Loup gris, le Loup rouge ou le coyote[5].

Les études moléculaires réalisées en 2003 suggèrent de nouveau que le Loup de l'Est est bien une espèce à part entière du Nouveau Monde, conspécifique avec le Loup rouge (Canis rufus Audubon et Bachman, 1851)[2],[6], en tout cas distincte et ayant évolué indépendamment du loup gris d'origine eurasienne, même s'ils se croisent fréquemment sur les mêmes territoires[6],[2]. Ceci a été confirmé en 2006[5] et aussi en 2010 par une étude réalisée sur les loups du parc provincial Algonquin, région où différentes populations se partagent le territoire tout en conservant des caractéristiques génétiques distinctes.

Le loup de l'Est est plus petit que le Loup gris. Il a une peau grisâtre-brun pâle. Le dos et les flancs sont couverts de longs poils noirs. Le dos de ses oreilles a une légère couleur rougeâtre.

Le loup de l'Est est également plus maigre que le Loup gris ce qui lui confère l'aspect d'un coyote. Cette allure de coyote est due aux multiples hybridations loup/coyote qui ont lieu fréquemment dans les parcs[3].

Les loups gris attaquent, tuent ou chassent les coyotes s'ils les trouvent ; des études menées en 1998 par John et Mary Theberge[7] suggèrent que les loups de l'Est mâles acceptent les femelles coyotes. John Theberge déclare que, parce que les coyotes sont plus petits que les loups, les louves seraient moins enclines à accepter un plus petit compagnon.

Au sein de ces populations mélangées, la taille des individus obtenus dépend du niveau d'hybridation du loup de l'Est avec les deux autres espèces de canidés, le loup gris (Canis lupus) et le coyote de l'Ouest (Canis latrans), qui ne peuvent pas s'hybrider entre elles[8].

Ce loup s'attaque principalement à des cervidés ou de plus petits mammifères. Contrairement aux loups gris qui sont globalement de plus grande taille, ils ne s'attaquent que très rarement aux orignaux, même s'ils sont abondants[8].

Si les proies du loup de l'Est sont donc principalement des cervidés comme le cerf de Virginie, ils capturent aussi volontiers de plus petits mammifères, des lagomorphes et des rongeurs, comprenant le castor, le rat musqué et les souris.

Les recherches menées au Canada au XXIe siècle[8],[2] identifient en fait deux types de loups sur ce territoire : le type Ontario, confiné principalement dans les forêts boréales et qui serait bien un Canis lupus et le type Algonquin d'espèce Canis lycaon que l'on rencontre aussi en forêt tempérée décidue[8].

Le loup de l'Est occupe principalement le secteur de l'aire protégée du Parc provincial Algonquin[4] qui est bordé au sud par une zone où vivent des coyotes hybrides (C. lycaon x C. latrans), nommés « Tweed wolf » en anglais[4]. On pense qu'il doit aussi se trouver au Minnesota et Manitoba. Dans le passé, ces espèces arrivaient peut-être plus en avant dans les États-Unis, mais après l'arrivée des Européens, ces loups ont été fortement persécutés dans le pays. Au Canada, le nombre exact de loups de l'Est est inconnu.

Dans l'Algonquin, des loups voyagent souvent en dehors des frontières du parc, et entrent dans des régions de fermes où certains sont tués. « De tous les décès de loup enregistrés de 1988 à 1999, un minimum de 66 % a été provoqué par des humains. Les frontières extérieures de tir du parc étaient les principales causes de décès pour des loups équipés de puces en parc d'Algonquin. »[7]. Un loup marqué en juillet 1992 a été repéré en octobre dans le Parc de la Gatineau, qui est à 170 kilomètres du parc d'Algonquin. Mi-décembre, il avait fait son retour dans l'Algonquin, puis, en mars 1993, la tête tranchée de ce loup a été trouvée clouée à un poteau de téléphone dans le Round Lake par un homme qui détestait les loups.

L'espèce Canis lycaon, formerait en fait une métapopulation[8],[4]. Cette métapopulation garde ainsi un haut degré de variabilité et d'adaptation qui lui permet de résister à la concurrence de l'homme mieux que le Loup gris dont les populations diminuent. Au contraire de leurs cousins gris, les populations ayant majoritairement un matériel génétique Canis lycaon, ou celles des coyotes avec lesquels ils se sont croisés, tendent à se développer[8].

Il est difficile d'estimer le nombre de Canis lycaon vivant dans la région supérieure des Grands Lacs, les différentes espèces de canidés s'y croisant et se mélangeant volontiers[2].

Le coyote et le loup de l'Est se ressemblent tellement qu'une interdiction de chasse a été instaurée pour tous les loups du Canada mais aussi pour les coyotes, de façon à éviter toute mort accidentelle, le loup gris, le loup de l'Est et le coyote se côtoyant sur le territoire canadien[9].

Selon Parcs Canada et les sociétés gérant les régions sauvages estiment que l'hybridation avec les coyotes peut être un danger pour la préservation de l'espèce Canis lycaon. Le Comité sur le statut de la faune du Canada (COSEWIC) a en effet identifié l'hybridation loup/coyote, comme étant l'une des menaces principales auxquelles faisaient face les loups de l'Est. L'hybridation continue à être également un défi sérieux pour le rétablissement du loup rouge en Caroline du Nord[3].

En 2008 une étude a montré qu'il est possible d'étudier ces loups de plus près sans occasionner de perturbations durables sur le comportement des familles, ni augmenter la mortalité des louveteaux[10] et les recherches qui ont été faites par ailleurs donnent des indications sur la répartition passée de ce loup des bois de l'est. Tout ceci aura des conséquences sur la gestion de la réintroduction des loups dans les États du nord-est américain[2].

Canis lycaon, Canis lupus lycaon

Le loup de l'Est (Canis lycaon) est un mammifère carnivore de la famille des Canidae que l'on trouve en Amérique du Nord. Les études génétiques réalisées au XXIe siècle confirment qu'il s'agit bien d'une espèce du Nouveau Monde à part entière et non pas d'une sous-espèce (Canis lupus lycaon) du Loup gris (Canis lupus) comme on l'a accepté un temps. En français, de nombreux noms ont été proposés pour le désigner (loup du Canada, loup gris de l'Est, loup rouge de l'Est, loup des bois de l'est...) mais c'est l'appellation Loup de l'Est qui est la plus courante.

Les populations de ce loup se rencontrent principalement au Canada, en particulier dans l'aire protégée du parc provincial Algonquin.

Il ne faut pas confondre Canis lycaon avec une autre espèce de Canidés bien différente, le lycaon (Lycaon pictus).

Il lupo orientale (Canis lupus lycaon) detto anche lupo dell'Algonquin, lupo canadese, lupo dei boschi o lupo cervo,[1][2] è un canide lupino di tassonomia controversa indigeno della regione dei grandi laghi del nordamerica. È un canide di taglia media che, come il lupo rosso, è intermedio in grandezza fra il coyote e gli altri lupi nordamericani come il lupo nordoccidentale. Si ciba principalmente di cervi della Virginia, ma può anche cacciare gli alci e i castori.[3][4] Non va confuso con il Canis lupus columbianus una sottospecie diretta del lupo grigio.

Lo stato tassonomico del lupo orientale è stato dibattuto sin dal 2000, con certi studiosi dichiarando che sia un conspecifico del lupo rosso,[5][6] una sottospecie di lupo grigio,[7] una specie a parte,[5][8] o un ibrido tra il coyote e il lupo grigio.[9][10] Attualmente, viene classificato come sottospecie di lupo grigio da MSW3,[11] e come specie distinta dalla United States Fish and Wildlife Service e il Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, che lo assegna lo stato di "specie a rischio".[1]

Il lupo orientale fu prima descritto scientificamente nel 1777 dal naturalista tedesco Johann Schreber, che lo terminò loup noir (lupo nero). La sua rappresentazione dell'animale però lo mostrava con un manto nero, un colore insolito nel lupo orientale.[8] Fu classificato come una sottospecie piccola di lupo grigio da Edward Alphonso Goldman, sebbene notò una superficiale assomiglianza alle razze più grandi del lupo rosso.[12]

La classifica di Goldman rimase indiscusso fino all'avvento della biologia molecolare. Nel 2000, studi condotti sulle impronte genetiche nei microsatelliti dei lupi orientali presenti nel Parco Provinciale di Algonquin rivelarono sommiglianze significanti tra i lupi orientali e il lupo rosso, giungendo alla conclusione che i due fossero della stessa specie. Fu proposto che i due si fossero evoluti indipendentemente dal lupo grigio, e che si divisero dal coyote 150,000-300,000 anni fa.[5] Questa conclusione non fu universalmente accettata,[13][14] e la MSW3[11] classificò entrambi come sottospecie di lupo grigio nel 2005.

Il dibattito fu riacceso nel 2011 con un'analisi di 48,000 polimorfismi a singolo nucleotide di cani e lupi nordamericani che suggerì che entrambi il lupo orientale e il lupo rosso fossero ibridi tra lupi grigi e coyote, con il lupo orientale essendo predominantemente di origine lupo, con 58% del suo genoma risalente al lupo grigio.[15] Questa scoperta fu criticata l'anno dopo, siccome gli esemplari di lupo orientale non provenivano dalle zone in cui si ritiene la specie sia pura.[16] Un ulteriore studio sul cromosoma Y dei lupi orientali, grigi e rossi un anno dopo mantenne la posizione che il lupo orientale e rosso fossero specie distinte, ma concese che i due si accoppiano volentieri con i coyote.[17] Fu proposto che i lupi rossi ed orientali con strutture sociali intatte sono meno disposti ad incrociarsi con i coyote.[18] Nel 2014, la controversia sullo stato tassonomico del lupo orientale fu assoggettato a una rivista comprensiva sugli studi condotti nel 2011 e 2012, che concluse che i lupi rossi ed orientali sono specie distinte dal lupo grigio.[8] Questa conclusione non fu accettata come definitiva dalla United States Fish & Wildlife Service.[19]

Nel 2015, uno studio genetico esaminando il DNA mitocondriale, cromosoma Y e il genoma da 127,235 SNP concluse che la spiegazione più "parsimoniosa" fosse che i lupi orientali del Parco Provinciale di Algonquin fossero gli ultimi esemplari d'un lupo che storicamente esisteva in un areale che inglobava tutti gli Stati Uniti d'America orientali.[20]

Nel 2016, lo sequenziamento dell'intero genoma del lupo grigio e il coyote rivelò che le due specie si sono diversificate solo 6,000-117,000 anni fa, e che tutti i lupi nordamericani possiedono geni risalenti ai coyote. Entrambi il lupo orientale e il lupo rosso furono trovati d'avere la quantità massima di geni di coyote fra i lupi nordamericani.[10][21] Questo ritrovamento fu rafforzato da un ulteriore studio sul DNA mitocondriale[22] e un ulteriore sequenziamento genomico, che dimostrò che 60% del suo DNA è risalente al lupo grigio e 40% al coyote.[23]

La sua pelliccia è tipicamente d'un colore grigiastro bruno variegato con sfumature di rosso cannella. Al contrario di altri lupi nordamericani, il lupo orientale produce esemplari melanici solo raramente.[2] Similmente al lupo rosso, il lupo orientale è intermedio in grandezza tra il coyote e il lupo nordoccidentale, con le femmine adulte pesando 23.9 chili e i maschi 30.3. Come il lupo grigio, la sua longevità e mediamente tra i 3-4 anni, con un massimo di 15.[3] La loro taglia sembra essere correlata con la loro alimentazione a base di prede di taglia medie.[9]

Si nutre principalmente di prede di taglia media come i cervi della Virginia e i castori, in contrasto al lupo grigio che può abbattere prede grosse come le renne, i wapiti, gli alci e i bisonti.[4] I territori tendono a variare in areale dai 110–185 km²,[3] e i cuccioli attengono l'indipendenza all'età di 15 settimane, che è molto più ritardato nei lupi grigi.[4]

Il lupo svolgeva un ruolo importante nella mitologia degli algonchini, che lo nominavano ma-hei-gan o nah-poo-tee nelle loro lingue. Viene rappresentato come il fratello spirituale dell'eroe nazionale algonchino Nanabozho, accompagnandolo nelle sue varie avventure, incluso nello sventare il complotto degli spiriti maliziosi anamakqui e nel ricreare il mondo dopo un diluvio universale.[24]

Prima della colonizzazione europea delle Americhe, è probabile che ci fosse una popolazione di 64,500-90,200 lupi orientali.[16] Il suo areale inglobava le zone forestali e aperte del nordamerica orientale, dalle province marittime e il Quebec meridionale fino agli Stati Uniti meridionali e a ovest fino alle Grandi Pianure. Gli indigeni di quelle zone non temevano i lupi, sebbene li catturassero ogni tanto in trappole, e le loro ossa sono state rinvenute nelle discariche antiche.[25] I resoconti scritti più vecchi riguardo al lupo orientale vengono da Jacques Cartier nel 1535 e dal Histoire de la Nouvelle-France di Marc Lescarbot nel 1609. Quest'ultimo scrisse che l'animale era comune in Accadia.[26]

I pionieri europei spesso tenevano il bestiame su isolette prive di lupi, siccome gli animali al pascolo sull'entroterra erano troppo vulnerabili, giungendo a una campagna di sterminio di lupi negli anni dopo la fondazione delle colonie di Plymouth e Massachusetts Bay. In entrambi i casi, parteciparono sia i coloni che i nativi. Un sistema di taglie fu cominciato, con ricompense più elevate per i lupi adulti, le cui teste furono esposte nei comuni. I lupi orientali erano comunque ancora abbastanza comuni nel diciottesimo secolo da obbligare gli abitanti di Sandwich e Wareham a discutere sulla possibilità di erigere un recinto enorme per separare i lupi dai pascoli. Il progetto fallì, ma i pionieri continuarono a scavare fosse per intrappolare i lupi, una tecnica imparata dalle popolazioni indigene. La popolazione di lupi orientali decrementò notevolmente poco prima e dopo la guerra d'indipendenza americana, soprattutto in Connecticut, dove il sistema di taglie fu revocato nel 1774. I loro numeri erano ancora abbastanza elevati nelle zone poco abitate del New Hampshire meridionale e Maine, con la caccia al lupo diventando un'occupazione regolare per i pionieri e i nativi. Nei primi anni 1800, ne rimanevano pochi esemplari nel New Hampshire meridionale e Vermont.[25]

Prima dell'apertura di Algonquin Provincial Park nel 1893, il lupo orientale era comune nell'Ontario centrale e negli altopiani algonchini. Continuò a persistere negli ultimi anni 1800, malgrado la deforestazione e la caccia attiva da parte delle guardie forestali, probabilmente a causa delle prede abbondanti come cervi e castori. Nel mezzo del 1900, furono contati almeno 55 branchi nel parco,[27] con circa 49 lupi abbattuti all'anno tra il 1909 e il 1958, fino a che non furono dati protezione dal governo di Ontario nel 1959, quando la popolazione dei lupi nei confini del parco fu ridotta a 500-1000 esemplari.[16][27] In ogni caso, nel 1964-1965, 3% della popolazione del parco fu abbattuta dai ricercatori cercando di studiare la sua riproduzione e struttura d'età. Questo eccidio coincise con l'arrivo di coyote nel parco, che risultò nell'incrociamente tra le due specie.[16] Incrociamenti con lupi non indigeni del parco ebbero anche luogo lungo l'Ontario settentrionale ed orientale, in Manitoba, Quebec, e nelle regioni occidentali dei Grandi Laghi di Minnesota, Wisconsin e Michigan.[4] Malgrado la protezione legale, ci fu un declino nella popolazione di lupi nella regione orientale del parco nel 1987-1999, con solo 30 branchi contati nel 2000. Questo declino superava il reclutamento annuale di lupi nei branchi, e fu attribuito alle uccisioni da parte umana, normalmente succedendo quando lupi vagranti uscivano dalle frontiere del parco per inseguire i cervi durante l'inverno.[27] Nel 2001, la protezione fu estesa ai lupi presso i confini del parco, e nel 2012, la loro composizione genetica ritornò ai livelli relativamente non inquinati degli anni sessanta.[16]

Nella prima versione della Lista Rossa IUCN, questo lupo veniva considerato come dipendente dalla consrvazione (cd). Dal momento che questa categoria non è più in uso, possiamo considerarlo come prossimo alla minaccia (nt), anche se non è la classificazione propriamente corretta.

Il lupo orientale (Canis lupus lycaon) detto anche lupo dell'Algonquin, lupo canadese, lupo dei boschi o lupo cervo, è un canide lupino di tassonomia controversa indigeno della regione dei grandi laghi del nordamerica. È un canide di taglia media che, come il lupo rosso, è intermedio in grandezza fra il coyote e gli altri lupi nordamericani come il lupo nordoccidentale. Si ciba principalmente di cervi della Virginia, ma può anche cacciare gli alci e i castori. Non va confuso con il Canis lupus columbianus una sottospecie diretta del lupo grigio.

Lo stato tassonomico del lupo orientale è stato dibattuto sin dal 2000, con certi studiosi dichiarando che sia un conspecifico del lupo rosso, una sottospecie di lupo grigio, una specie a parte, o un ibrido tra il coyote e il lupo grigio. Attualmente, viene classificato come sottospecie di lupo grigio da MSW3, e come specie distinta dalla United States Fish and Wildlife Service e il Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, che lo assegna lo stato di "specie a rischio".

Austrumu vilks (Canis lycaon) ir suņu dzimtas (Canidae) plēsējs, kas pieder pie suņu ģints (Canis). Daudzi sistemātiķi austrumu vilku joprojām sistematizē arī kā vienu no pelēkā vilka (Canis lupus) pasugām ar latīnisko nosaukumu Canis lupus lycaon. Tomēr pēdējā laikā zinātnieki uzskata, ka austrumu vilks būtu jāizdala kā patstāvīga suga[1], jo tas tāpat kā sarkanais vilks (Canis rufus) un koijots (Canis latrans) ir atdalījies no pelēkā vilka pirms vairākiem simtiem tūkstošiem gadu[2].

Austrumu vilks pamatā apdzīvo Algonkvinas dabas parku Ontārio, Kanādā, kā arī tas ir novērots Kvebekas apkārtnē, Minesotas un Manitobas reģionos ASV. Kādreiz austrumu vilks apdzīvoja plašas teritorijas uz dienvidiem ASV, bet līdz ar eiropiešu iebraukšanu Amerikā vilks tika nežēlīgi iznīcināts. Šobrīd austrumu vilka izdzīvošana skaitās kritiski apdraudēta.

Austrumu vilks ir mazāks nekā pelēkais vilks. Tā augstums skaustā 60 - 68 cm, svars 25 - 35 kg tēviņiem, 20 - 30 kg mātītēm[3]. Tam ir dzeltenīgi pelēkbrūns kažoks. Mugura un sāni klāti ar garu, melnu vai pelēku akotspalvu. Aiz ausīm, uz purna un uz priekškājām apspalvojums ir sarkanīgs[4]. Ārēji tas ir līdzīgs sarkanajam vilkam. Austrumu vilka ķermeņa uzbūve ir vieglāka kā pelēkajam vilkam un tā skelets ir līdzīgāks koijotam. Ir zināms, ka austrumu vilks bieži krustojas ar koijotu,[4] un zinātnieki uzskata, ka vilka izdzīvošanai savvaļā vislielākās briesmas draud tieši no krustošanās ar koijotiem. Pelēkais vilks vienmēr uzbrūk koijotam un pie pirmās izdevības to nogalina, bet austrumu vilka tēviņi pieņem koijotu mātītes. Tā kā koijoti kopumā ir mazāki par austrumu vilkiem, tad vilku mātītes nepieņem mazos koijotu tēviņus.

Austrumu vilks medī baltastes briežus, alņus un dažādus grauzējus, piemēram, bebrus, lagomorfus, muskatžurkas un peles. Ir ziņas, ka austrumu vilks ir nomedījis pat Amerikas melno lāci. Pētījumi liecina, ka visbiežāk tiek medīti aļņi, baltastes brieži un bebri.

Vilku barā pārojas tikai alfa mātīte ar alfa tēviņu. Tas parasti notiek februārī. Grūsnības periods ilgst 63 dienas. Kucēni dzimst alā, ko izrok vecāki. Parasti piedzimst 4-7 kucēni. Pirmās 6 - 8 nedēļas māte no tiem neatkāpjas ne soli. Viss bars baro māti un vēlāk arī mazuļus, kad mēte tos ir pārstājusi zīdīt. Barība tiek atnesta apēstā veidā, kas tiek mazuļiem atvemta. Vasaras beigās mazuļi pamet alu, un tie parasti tiek atstāti kādā plašā pļavā, kamēr bars ir devies medībās. Pļavas sauc par vilku rotaļu laukumiem, šīs teritorijas ir labi izvēlētas, ar dabiskiem slēpņiem un aizsegiem, vienmēr tuvumā ir ūdens, kā arī pļavā dzīvo daudzi dažādi mazi dzīvnieciņi, kurus dienas laikā jaunie vilcēni cenšas nomedīt, tādā veidā attīstot savas medību iemaņas[4].

Zinātniekiem, veicot ģenētiskos pētījumus, ir noskaidrojuši, ka austrumu vilka vistuvākais radinieks ir sarkanais vilks[5]. Ir zinātnieki, kas uzskata, ka tās vispār nav divas atšķirīgas sugas. Šis viedoklis joprojām nav oficiāls. DNS pētījumi liecina, ka austrumu un sarkanais vilks atdalījušies no primitīvā pelēkā vilka pirms 750 000 gadiem Ziemeļamerikas austrumu teritorijās un ka austrumu vilku un sarkano vilku vajadzētu uzskatīt par divām pasugām sarkanajam vilkam.

Austrumu vilks (Canis lycaon) ir suņu dzimtas (Canidae) plēsējs, kas pieder pie suņu ģints (Canis). Daudzi sistemātiķi austrumu vilku joprojām sistematizē arī kā vienu no pelēkā vilka (Canis lupus) pasugām ar latīnisko nosaukumu Canis lupus lycaon. Tomēr pēdējā laikā zinātnieki uzskata, ka austrumu vilks būtu jāizdala kā patstāvīga suga, jo tas tāpat kā sarkanais vilks (Canis rufus) un koijots (Canis latrans) ir atdalījies no pelēkā vilka pirms vairākiem simtiem tūkstošiem gadu.

Austrumu vilks pamatā apdzīvo Algonkvinas dabas parku Ontārio, Kanādā, kā arī tas ir novērots Kvebekas apkārtnē, Minesotas un Manitobas reģionos ASV. Kādreiz austrumu vilks apdzīvoja plašas teritorijas uz dienvidiem ASV, bet līdz ar eiropiešu iebraukšanu Amerikā vilks tika nežēlīgi iznīcināts. Šobrīd austrumu vilka izdzīvošana skaitās kritiski apdraudēta.

Serigala timur (Canis lycaon), juga dikenali sebagai serigala Tasik-tasik Besar, serigala balak timur, serigala Algonquin atau serigala rusa[2] ialah sejenis canid yang asli di bahagian timur laut rantau Tasik-tasik Besar Amerika Utara.[3] Ia merupakan spesies bersaiz sederhan yang, seperti serigala merah, berwarna kemerah-merahan-perang dan bersaiz antara koyote dengan serigala kelabu. Ia terutamanya memangsakan rusa berekor putih, tetapi kadang-kadang boleh menyerang moose dan beaver.[4][5]

Identiti taksonomi serigala timur telah menjadi subjek kontroversi, dengan beberapa teori berlainan dibentangkan mengenai asal usulnya, termasuk bahawa ia merupakan satu subspesies serigala kelabu,[1] bahawa ia konspesifik dengan serigala merah,[6][7] bahawa ia merupakan hasil daripada pengacukan serigala kelabu-koyote,[8] dan bahawa ia merupakan satu spesies unik.[6][9] Setakat 2005[update],[1] serigala timur masih diakui sebagai satu subspesies serigala kelabu oleh MSW3, tetapi dikelaskan sebagai spesies tersendiri oleh Perkhidmatan Ikan dan Hidupan Liar Amerika Syarikat pada 2013 selepas ulasan menyeluruh bagi beberapa kajian genetik. Kajian-kajian ini menunjukkan bahawa serigala timur berubah ansur di Amerika Utara, tidak seperti serigala kelabu yang berasal dari Eurasia, dan mencapah daripada leluhur sepunya dengan koyote dan serigala merah pada 150,000–300,000 tahun lalu.[9]