en

names in breadcrumbs

Hoplostethus atlanticus, auch Kaiserbarsch, Orange Roughy oder Granatbarsch genannt, ist ein relativ großer Tiefseefisch. Er kommt in kalten (3–9 °C), tiefen (bathypelagisch, ca. 180–1800 m) Gewässern des Westatlantiks (nördlich von Neuschottland), Ostatlantiks (von Island bis Marokko, Namibia bis Südafrika), zwischen Neuseeland und Australien sowie im Ostpazifik vor Chile vor.[1]

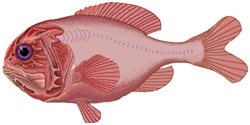

Der Granatbarsch ist mit einer maximalen Größe (inklusive Schwanzflosse) von 75 cm und einem maximalen Gewicht von 7 kg der bisher größte bekannte Vertreter der Trachichthyiformes. Jedoch haben die meisten kommerziell gefangenen Exemplare standardmäßig nur eine Größe von 30 bis 40 cm Hoplostethus atlanticus ist auffällig ziegelrot gefärbt, das Innere des Mauls und das Innere der Kiemen ist schwarzblau. Die Schuppen sind klein und unregelmäßig angeordnet.[1]

Von anderen, ähnlich gefärbten Fischen kann Hoplostethus atlanticus durch seinen großen verknöcherten Kopf, die kleinen, unregelmäßig angeordneten Schuppen und die zahlreichen Schuppen am Bauch unterschieden werden.[2]

Der Orange Roughy ist bekannt dafür, dass er sehr alt (bis ca. 150 Jahre) werden soll und sein fortpflanzungsfähiges Alter erst mit ca. 30–35 Jahren erreicht.[3] Diese Angaben sind allerdings umstritten; über den wirklichen Lebenszyklus der Tiere ist wenig bekannt. Sollten sie stimmen, sind viele der heute gefischten Exemplare vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg geschlüpft. Die Bestände dürften sich dann äußerst langsam erholen und unter Beibehaltung derzeitiger Fangmengen rasch erschöpft sein.[3] Welche Rolle der Granatbarsch im Ökosystem der Tiefsee spielt und welche Folgen sein Verschwinden für andere Arten hat, ist bislang nicht ausreichend geklärt. Sicher ist, dass er in Schwärmen lebt, die alle Altersstufen umfassen und weite Wanderungen unternehmen. Dabei folgen sie eventuell Tiefseeströmungen.

Der Fisch ist für die Tiefseefischerei von großer Bedeutung und wird häufig im Handel als Speisefisch angeboten. Er wird auch in Deutschland verkauft, aber vor allem in Großbritannien, den USA, in China und Australien gegessen.[3] Seine ziegelrote Farbe schwächt sich nach dem Tod zu einem gelblichen Orange ab. Der Granatbarsch kann maximal 75 cm lang und 7 kg schwer werden. Jedoch haben die meisten kommerziell gefangenen Exemplare standardmäßig nur eine Größe von 30–40 cm.

Im Jahr 2007 verboten die Regierungen von Neuseeland und Australien die Orange-Roughy-Fischerei auf unbestimmte Zeit, da die Bestände kollabiert waren.[4] Nachdem die beiden Staaten ein Überwachungs- und Erholungsprogramm einführten, erhielt die Orange-Roughy-Fischerei Ende 2016 die MSC-Zertifizierung und der Fisch darf wieder gefangen werden.[5]

Hoplostethus atlanticus, auch Kaiserbarsch, Orange Roughy oder Granatbarsch genannt, ist ein relativ großer Tiefseefisch. Er kommt in kalten (3–9 °C), tiefen (bathypelagisch, ca. 180–1800 m) Gewässern des Westatlantiks (nördlich von Neuschottland), Ostatlantiks (von Island bis Marokko, Namibia bis Südafrika), zwischen Neuseeland und Australien sowie im Ostpazifik vor Chile vor.

Búrfiskur (frøðiheiti - Hoplostethus atlanticus) verður til støddar uml. 70 cm. Hann er hávaksin við stórum høvdi, hægstur (1/3 av longdini) beint aftan fyri høvdið. Kjafturin er stórur, svartur innan og stendur á skák. Hann hevur fleiri píkar á høvdinum, og roðslan eftir strikuni er beinakend og á hesum fiskaslagi størri enn annars. Liturin á kroppinun er fagurt reyðgulur, og høvdið reytt. Í Norðuratlanshavi er hann undir Íslandi og suður til Biskayavíkina og við Azorurnar. Annars livir hann á sunnaru hálvu. Við New Zealand, Australia og Tasmania eru tað í fleiri ár fiskaðar stórar nøgdir av búrfiski. Á okkara leiðum er hann fyri tað mesta fingin djúpari enn 600 m og oftast fram við brøttum hellingum og fram við tindum í sjónum. Á sunnaru hálvu veksur fiskurin sera spakuliga, og í Australia rokna fiskifrøðingar við, at bert uml. 3% av samlaðu stovnunum kunnu fiskast árliga, uttan at stovnurin minkar.

Búrfiskur (frøðiheiti - Hoplostethus atlanticus) verður til støddar uml. 70 cm. Hann er hávaksin við stórum høvdi, hægstur (1/3 av longdini) beint aftan fyri høvdið. Kjafturin er stórur, svartur innan og stendur á skák. Hann hevur fleiri píkar á høvdinum, og roðslan eftir strikuni er beinakend og á hesum fiskaslagi størri enn annars. Liturin á kroppinun er fagurt reyðgulur, og høvdið reytt. Í Norðuratlanshavi er hann undir Íslandi og suður til Biskayavíkina og við Azorurnar. Annars livir hann á sunnaru hálvu. Við New Zealand, Australia og Tasmania eru tað í fleiri ár fiskaðar stórar nøgdir av búrfiski. Á okkara leiðum er hann fyri tað mesta fingin djúpari enn 600 m og oftast fram við brøttum hellingum og fram við tindum í sjónum. Á sunnaru hálvu veksur fiskurin sera spakuliga, og í Australia rokna fiskifrøðingar við, at bert uml. 3% av samlaðu stovnunum kunnu fiskast árliga, uttan at stovnurin minkar.

The orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), also known as the red roughy, slimehead and deep sea perch, is a relatively large deep-sea fish belonging to the slimehead family (Trachichthyidae). The UK Marine Conservation Society has categorized orange roughy as "vulnerable to exploitation". It is found in 3 to 9 °C (37 to 48 °F), deep (bathypelagic, 180-to-1,800-metre (590 to 5,910 ft)) waters of the Western Pacific Ocean, eastern Atlantic Ocean (from Iceland to Morocco; and from Walvis Bay, Namibia, to off Durban, South Africa), Indo-Pacific (off New Zealand and Australia), and in the eastern Pacific off Chile. The orange roughy is notable for its extraordinary lifespan, attaining over 200 years. It is important to commercial deep-trawl fisheries. The fish is a bright, brick-red color, fading to a yellowish-orange after death.

Like other slimeheads, orange roughy is slow-growing and late to mature, resulting in a very low resilience, making them extremely susceptible to overfishing. Many stocks (especially those off New Zealand and Australia, which were first exploited in the late 1970s), became severely depleted within 3–20 years, but several have subsequently recovered to levels that fisheries management believe are sustainable, although substantially below unfished populations.

The orange roughy is not a vertically slender fish. Its rounded head is riddled with muciferous canals (part of the lateral line system), as is typical of slimeheads. The single dorsal fin contains four to six spines and 15 to 19 soft rays; the anal fin contains three spines and 10 to 12 soft rays. The 19 to 25 ventral scutes (modified scales) form a hard, bony median ridge between the pelvic fins and anus. The pectoral fins contain 15 to 18 soft rays each; the pelvic fins are thoracic and contain one spine and six soft rays; the caudal fin is forked. The interior of the mouth and gill cavity is a bluish black; the mouth itself is large and strongly oblique. The scales are ctenoid and adherent. The lateral line is uninterrupted, with 28 to 32 scales whose spinules or 'ctenii' largely obscure the lateral line's pores. The eyes are large.

The orange roughy is the largest known slimehead species at a maximum standard length (a measurement that excludes the tail fin) of 75 cm (30 in) and a maximum weight of 7 kg (15 lb). The average commercial catch size is commonly between 35 and 45 centimetres (14 and 18 in) in length, again, varying by area.

Orange roughy are generally sluggish and demersal; they form aggregations with a natural population density of up to 2.5 fish per m2, now reduced to about 1.0 per m2. These aggregations form in and around geologic structures, such as undersea canyons and seamounts, where water movement and mixing is high, ensuring dense prey concentrations. The aggregations are not necessarily for spawning or feeding; the fish are thought to cycle through metabolic phases (active or feeding and inactive or resting) and seek areas with ideal hydrologic conditions to congregate during each phase. They lose almost all pigmentation while inactive, when they are very approachable. Predators include large, deep-roving sharks, cutthroat eels, merluccid hakes, and snake mackerels.

When active, juveniles feed primarily on zooplankton such as mysid shrimp, euphausiids (krill), mesopelagic and benthopelagic fish, amphipods, and other crustaceans; mature adults consume smaller fish, predominantly of the Butterflyfish and Lanternfish families, and squid, which make up to 20% of their diet. The diet of the orange roughy is depth-related, with adult diets inversely related to that of juveniles. For example, juvenile consumption of crustaceans is lowest at 900 metres (3,000 ft) but increases with depth, while crustaceans in the adult diet peak at 800–1,000 metres (2,600–3,300 ft) and decrease with depth. The consumption of fish is the opposite: juvenile consumption decreases with depth while adult consumption increases. This inverse feeding pattern may be an example of resource-partitioning to avoid intraspecific competition for the available food at depths where prey is less abundant. The orange roughy's metabolic phases are thought to be related to seasonal variations in prey concentrations. The inactive phase conserves energy during lean periods. Orange roughy can live for over 200 years.[2]

Orange roughy are oceanodromous (wholly marine), pelagic spawners: that is, they migrate several hundred kilometers between localized spawning and feeding areas each year and form large spawning aggregations (possibly segregated according to gender) wherein the fish release large, spherical eggs 2.0–2.5 millimetres (0.079–0.098 in) in diameter, made buoyant by an orange-red oil globule) and sperm en masse directly into the water. The fertilized eggs, (and later larvae) are planktonic, rising to around 200 m (660 ft) to develop, with the young fish eventually descending to deeper waters as they mature. Orange roughy are also synchronous, shedding sperm and eggs at the same time. The time between fertilization and hatching is thought to be 10 to 20 days; fecundity is low, with each female producing only 22,000 eggs per kg of body weight, less than 10% of the average for other species of fish. Females rarely produce more than 90,000 eggs in one lifetime.[3] Spawning may last up to three weeks and starts around June or July. Orange roughy are very slow-growing and do not begin to breed until they are at least 20 years old, when they are around 30 cm (12 in) in length.[4]

The maturation age used in stock assessments ranges from 23–40 years,[5][6] which limits population growth/recovery, because each new generation takes so long to start spawning.[5]

When commercial fishing of orange roughy began in the 1970s, they were thought to live for only 30 years.[2] Since the 1990s, however, there is clear evidence that this species lives to an exceptional age. Early estimates of 149 years were determined via radiometric dating of trace isotopes found in an orange roughy's otolith (ear bone);[7] counting by the growth rings of orange roughy otoliths gave estimated ages of 125 to 156 years.[8] One specimen caught 1500 km east of Wellington in 2015 was estimated to be over 230 years old.[2] Orange roughy caught near Tasmania have been aged at 250 years.[2] The orange roughy is the longest-lived commercial fish species, and does not breed every year, which has important implications for its conservation status.[9]

The flesh is firm with a mild flavour; it is sold skinned and filleted, fresh or frozen.[10] This species was first given the common name "Orange Roughy" by scientists in New Zealand in 1975 following the discovery of large aggregations during a deep-water research cruise.[11][12][13] A large scale fishery for orange roughy subsequently developed around New Zealand, and imports into the United States increased where it was renamed from the less gastronomically appealing "slimehead" through a U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service program during the late 1970s that identified underused species that should be renamed to make them more marketable.[14]

Historically, the United States has been the largest consumer of orange roughy, however, in recent years, the market for orange roughy in China has increased significantly. In 2014, the U.S. imported around 1,455 tonnes (4.4 million lb) (mainly fillets) from New Zealand, China, Peru and Indonesia. In 2015, China imported at least 4,000 tonnes (8.8 million lb) (mainly whole fish).

A number of major food retailers have established seafood sustainability policies to reassure customers that they are stocking sustainable seafood. These policies often involve partnering with non-governmental organizations to define criteria for seafood that may be stocked. In addition, a number of ecolabels exist to help retailers and consumers identify seafood that has been independently assessed against a robust, scientific standard. One of the best known such programmes is that of the Marine Stewardship Council.

In 2010, Greenpeace International added orange roughy (deep sea perch) to its seafood red list, which contains fish generally sourced from unsustainable fisheries.[15]

A 2003 joint report by the TRAFFIC Oceania and World Wildlife Foundation Endangered Seas Program argues, "probably no such thing [exists] as an economically viable deep-water fishery that is also sustainable."[16] However, others have argued that deepwater fisheries can be managed sustainably provided that it is recognized that sustainable yields are low and catches are set accordingly.[17][18]

Because of its longevity, the orange roughy accumulates large amounts of mercury in its tissues, having a range of 0.30–0.86 ppm compared with an average mercury level of 0.086 ppm for other edible fish.[19] Based on average consumption and the recommendations of a National Marine Fisheries Service study, in 1976 the FDA set the maximum safe mercury level for fish at 1 ppm.[20] Regular consumption of orange roughy can have adverse effects on health.[21][22] Compared to most edible fish, orange roughy is a very poor source of omega-3 fatty acids, averaging less than 3.5 g/kg.

Orange roughy fisheries exist in New Zealand, Australia and Namibia.[5] Annual global catches began in 1979 and increased significantly to a high of over 90,000 tonnes in the late 1980s. These high catch levels quickly decreased as stocks were fished down. For many stocks, the lack of understanding of the biological characteristics meant that they were overfished. By the end of the 1990s, three of the eight New Zealand orange roughy fisheries had collapsed and were closed.[2] Because its longevity, late maturation and relatively low fecundity, orange roughy stocks tend to recover slower than most other species.[5][23]

A number of orange roughy stocks live outside the jurisdiction of any particular nation, making it more challenging to limit overall catches. The South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation[24] (SPRFMO) and the South Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement[25] have orange roughy stocks that are managed within their jurisdictions. These organizations have made progress toward collecting better information on total orange roughy catches and also with setting catch limits for fisheries on the high seas. For example, SPRFMO limited orange roughy catches and effort from 2007.[26]

Orange roughy is fished almost exclusively by bottom trawling. This fishing method has been heavily criticized by environmentalists for its destructive nature. This, combined with heavy commercial demand, has focused criticism from both environmentalists and media.[27][28][29]

New Zealand currently operates the largest orange roughy fisheries in the world, with a total catch of over 8,500 tonnes in the 2014 calendar year. This accounts for 95% of the total estimated catch of orange roughy. Exports of orange roughy provided an estimated revenue to New Zealand of NZ$53 million (US$37M) in 2015.

Fisheries in New Zealand are managed through the Quota Management System (QMS), under which individuals or companies own quota shares for a stock of a particular species or species group. For each stock, a Total Allowable Catch (TAC) is set that maintains the stock at or above a level that can produce the maximum sustainable yield or that will move the stock toward that level. Orange roughy has been managed within the QMS since 1986.

The Ministry for Primary Industries is responsible for the implementation of the QMS and its enabling legislation, the Fisheries Act 1996.

Fishery farming of orange roughy was initiated in the mid-1970s, but full exploitation did not begin until 1979. There was no regulation of these early catches, and records indicate that they were very high. For many fisheries, management settings allow for a "fishing down" period during which the biomass is reduced to a level that will provide the maximum sustainable yield. For example, a fishery with a hypothetical unfished biomass of 100,000 tonnes will be allowed to be fished down to a biomass of 40,000 tonnes (assuming that this is the biomass that provides for the maximum sustainable yield) over a number of years. The rate of this "fish-down" can vary depending on the objectives of the fishery, but catches would then be more strictly controlled to maintain the biomass at around 40,000 tonnes.

For the New Zealand orange roughy fisheries, productivity parameters and resulting estimates of unfished biomass were incorrectly estimated in the first decade of the fishery. Catch limits exceeded recommended estimates of sustainable yields for a subsequent decade and catches were estimated to have exceeded those catch limits because of burst nets, escape windows in nets and lost gear. Catch limits were reduced in the mid-1990s, although they were increased again following indications that stocks had begun to rebuild. This was later found not to be the case and a number of fisheries were closed completely or had catch limits reduced to one tonne to allow the stocks to rebuild.

In one New Zealand fishery, the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) was reduced in 2008 from 1,470 tonnes to 914 tonnes, but this reduction was challenged in court. In February 2008, the High Court overturned the new quota, ruling that the Minister of Fisheries did not have the legal power to set quotas for ORH1. This was because of a strict interpretation of the Fisheries Act that required an accurate estimation of the biomass that could support the maximum sustainable yield. As a result of this decision, the Fisheries Act 1996 was amended to allow TACs to be set based on the best available information in the absence of an estimate of the biomass that could support the maximum sustainable yield.

The New Zealand fishing industry contracted a pre-assessment of selected orange roughy fisheries against the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) Fisheries Standard in 2009. Following the pre-assessment, the industry representative body (Deepwater Group Ltd) put four orange roughy fisheries into Fishery Improvement Plans (FIPs) to deliver improvements in the fisheries that would enable them to meet the certification requirements of the MSC. These FIPs are public and have been monitored by the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership.

In 2014, Bayesian model-based stock assessments were completed for four of New Zealand's main orange roughy stocks, one of which had been closed to fishing since 2000. The stock assessments used data collected by research surveys carried out by research organizations and the fishing industry. A key factor was the use of new acoustic technology, developed by the fishing industry, in recent surveys. The multi-frequency acoustic optical system (AOS) enables scientists to differentiate the types of fish acoustically ‘seen’ during the survey and works on slopes that previously made effective surveying impossible in some areas. The AOS also has the potential to allow scientists to see in real-time video, what is being measured by the survey. Other research-derived data were also critical to the success of the stock assessments, notably age-frequencies from improved ageing methods.

The 2014 stock assessments,[30] which were subject to a robust peer review process, indicated that three of the stocks had recovered enough to sustain increased catches. The TACs for these stocks were subsequently increased. The fourth stock was estimated to be at a low stock status and the TAC was reduced by over 40% to allow the stock to rebuild.

In addition, an industry sponsored Management Strategy Evaluation[31] was completed that provided an estimate of the biomass that could support the maximum sustainable yield (≈25–27% of the unfished biomass). Based on this output, the fishing industry agreed to aim to maintain the orange roughy stocks within a management target range of 30–50% of the unfished biomass. Further to this, a Harvest Control Rule was agreed that would define what catch limits should be given an estimate of stock status. Catch limits for those fisheries are currently consistent with the outputs of the agreed Harvest Control Rule. In May 2014, three orange roughy fisheries entered full assessment against the Marine Stewardship Council Fisheries Standard.

The Australian orange roughy fishery was not discovered until the 1970s, but by 2008, the biomass of some stocks remained high while others was estimated to be down to 10% of the unfished level after years of commercial fishing.[32] It was the first commercially sought fish to appear on Australia's threatened species list because of overfishing.[33] By late 2017, a number of Australian orange roughy fisheries had been re-opened.[34]

In July 2020, a leading US-based MSC consultancy (conformity assessment body or CAB) acting for a group of Australian eastern zone orange roughy quota holders, released a scoring report recommended that the orange roughy eastern zone stock be given Marine Stewardship Council accreditation, scoring the fishery and its management highly (289/300) in each of the three assessment principles. However, environmental groups the Australian Marine Conservation Society and World Wildlife Fund raised late objections. MSC's decision to allow objections from these two eNGOs who did not engage in the more than year long process in contravention of the MSC Standard is seen by many as raising questions about the independence and credibility of the standard itself.

The Arbitrator issued her decision in three iterations in early 2021 each following representations from the Appellants, CAB and Fishery Client. During the process the Australian Minister for fisheries wrote to the MSC explaining that although orange roughy was listed under Australia's EPBC Act (1999) that it was also managed under the Fisheries Management Act(1991) and Fisheries Administration Act (1991) and that the commercial take of orange roughy allowed continued recovery and that it is listed in a section of the EPBC Act that allowed this commercial take. However, the Arbitrator found that her view was that the standard could not have intended threatened species to be certified and that the goal for threatened species should be zero catch. Further, that because orange roughy was listed under the EPBC Act that it should be considered as an endangered, threatened and protected (ETP) species as part of MSC Principle 2 and could therefore not also be considered as a target or subject stock under Principle 1.

In her second decision (February 2021) the Arbitrator summarised her decision by stating, "This particular stock is, according to the CAB and I have no reason within my limited remit, to disagree with this view, well managed and currently sustainably fished in terms of the prevailing science. I do acknowledge therefore that the remand decision will be all the more unwelcome by the CAB and the fishery client. However, the difficulty, in my view, lies in the narrow terms of the Standard when read against the Australian ETP legislation. It is not open to me to go beyond my interpretation, in light of any views I might have on the otherwise sustainability of the stock and the suitability of the unit of assessment for certification. The remedy to this lies outside of this process in seeking a change either to the Australian legislation or clarity in the Standard.

The Fishery Client subsequently withdrew the stock from assessment. Documents from the objection process can be found here https://fisheries.msc.org/en/fisheries/australia-orange-roughy-eastern-zone-trawl/@@assessments.

The precedent set by this decision has raised questions about the future of MSC in Australia given that a number of fish species involved in existing MSC certificates are listed under the EPBC Act. The current apparent incompatibility of the MSC Standard and Australian legislation is one reason why the MSC system has been so slow to develop in Australia and that Australian consumers have little recognition of the MSC brand.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) {{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) The orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), also known as the red roughy, slimehead and deep sea perch, is a relatively large deep-sea fish belonging to the slimehead family (Trachichthyidae). The UK Marine Conservation Society has categorized orange roughy as "vulnerable to exploitation". It is found in 3 to 9 °C (37 to 48 °F), deep (bathypelagic, 180-to-1,800-metre (590 to 5,910 ft)) waters of the Western Pacific Ocean, eastern Atlantic Ocean (from Iceland to Morocco; and from Walvis Bay, Namibia, to off Durban, South Africa), Indo-Pacific (off New Zealand and Australia), and in the eastern Pacific off Chile. The orange roughy is notable for its extraordinary lifespan, attaining over 200 years. It is important to commercial deep-trawl fisheries. The fish is a bright, brick-red color, fading to a yellowish-orange after death.

Like other slimeheads, orange roughy is slow-growing and late to mature, resulting in a very low resilience, making them extremely susceptible to overfishing. Many stocks (especially those off New Zealand and Australia, which were first exploited in the late 1970s), became severely depleted within 3–20 years, but several have subsequently recovered to levels that fisheries management believe are sustainable, although substantially below unfished populations.

El reloj anaranjado o reloj del Atlántico es la especie Hoplostethus atlanticus,[2] un pez marino de la familia traquictiídeos, distribuida por el este y noroeste del océano Atlántico, sur del océano Pacífico y océano Índico.[3]

Es una especie inofensiva, muy pescada y ampliamente comercializada.[3] Los barcos de pesca los localizan esporádicamente formando densos cardumenes; se puede encontrar en el mercado fresco o congelado, siendo normal que se cocine frito o al horno.[4]

Aunque se han descrito capturas mucho mayores la longitud máxima es normalmente de unos 40 cm.[5] En la aleta dorsal tiene de 4 a 6 espinas y 15 a 19 radios blandos, mientras que en la aleta anal hay 3 espinas y 10 a 12 radios blandos; el color es rojo-ladrillo brillante, con las cavidades de boca y agallas de color azulado.[5]

Es un pez batipelágico y oceanódromo, que vive sedentario pegado al sustrato a una gran profundidad normalmente entre 400 y 900 m,[6] normalmente en aguas frías del talud continental, en cordilleras oceánicas y otros relieves altos marinos, donde vive disperso alimentándose de crustáceos y otros peces.[3]

El crecimiento es muy lento, siendo uno de los peces más longevos que existen con un espécimen capturado con una edad de 149 años.[7] Muy poco se sabe sobre sus larvas y juveniles, que habitan probablemente en aguas abisales.[8]

El reloj anaranjado o reloj del Atlántico es la especie Hoplostethus atlanticus, un pez marino de la familia traquictiídeos, distribuida por el este y noroeste del océano Atlántico, sur del océano Pacífico y océano Índico.

Erloju-arrain laranja (Hoplostethus atlanticus) Hoplostethus generoko animalia da. Arrainen barruko Trachichthyidae familian sailkatzen da.

Espezie hau Agulhasko itsaslasterran aurki daiteke.

Erloju-arrain laranja (Hoplostethus atlanticus) Hoplostethus generoko animalia da. Arrainen barruko Trachichthyidae familian sailkatzen da.

Hoplostethus atlanticus

L'hoplostèthe orange, hoplostèthe rouge ou poisson-montre (Hoplostethus atlanticus) est une espèce de poissons de la famille des Trachichthyidae. L'hoplostèthe orange vit dans tous les océans entre 900 et 1 800 m de profondeur. Il a une longévité potentielle d'au moins 149 ans[1] et il n'atteint sa maturité sexuelle qu'entre 20 et 30 ans. Avec une longueur maximale de 75 cm pour 7 kg, c'est le plus grand de sa famille.

Commercialisé sous le nom d'empereur, il fait l'objet d'une importante exploitation commerciale, mais en raison de son faible recrutement, ses populations tendent à diminuer. De nombreux stocks, en particulier ceux de la Nouvelle-Zélande et de l'Australie, qui ont été exploités dans les années 1970, ont déjà été décimés ; les stocks de substitution récemment découverts s'épuisent rapidement.

L'hoplostèthe orange est rouge lorsqu'il est vivant, mais devient progressivement orange, une fois mort. C'est la plus grande espèce de la famille des Trachichthyidés, avec une longueur maximale de 75 cm et un poids maximum de 7 kg[2]. La taille moyenne des captures commerciales est située entre 35 et 45 cm de longueur[3],[4].

Sa tête arrondie est criblée de canaux muqueux, ce qui est typique des Trachichthyidés. L'unique nageoire dorsale est composée de quatre à six épines et de 15 à 19 rayons mous ; la nageoire anale comporte trois épines et 10 à 12 rayons mous. Les 19 à 25 écailles ventrales (écailles modifiées) forment une crête osseuse médiane entre les nageoires pelviennes et l'anus. Les nageoires pectorales ont 15 à 18 rayons mous chacune ; les nageoires pelviennes sont thoraciques et possèdent une épine et six rayons mous ; la nageoire caudale est fourchue. L'intérieur de la bouche et la cavité branchiale sont d'un noir bleuté, la bouche elle-même est grande et fortement oblique. Les écailles sont cténoïdes et adhérentes[5],[6].

L'hoplostèthe orange est généralement inactif et démersal, il forme de grands bancs d'une densité moyenne de 2,5 poissons par mètre carré, maintenant réduit à environ 1 par mètre carré à cause de la surpêche. Ces agrégats se forment dans et autour des structures géologiques, telles que les canyons sous-marins et les monts sous-marins, où les courants assurent un apport de proies abondant. Ce n'est pas nécessairement pour frayer ou s'alimenter qu'ils se réunissent : ces agrégats assurent une protection pendant les périodes d'inactivité. En effet, le cycle biologique de l'hoplostèthe orange traverse des phases métaboliques distinctes, d'activité consacrées à l'alimentation, et d'inactivité et de repos, durant laquelle ils perdent la quasi-totalité de leur pigmentation et sont vulnérables. Les bancs recherchent, en fonction de chaque phase, les zones possédant les conditions hydrologiques les plus favorables à ces rassemblements. Les prédateurs de l'hoplosthète orange comprennent certains requins, des anguilles égorgées, des merlus et l'escolier serpent.

Lorsqu'il est actif, il se nourrit principalement de zooplancton tel que les mysidacés (en) et les euphausiacés, de poissons mésopélagiques et benthopélagiques, d'amphipodes, de petits céphalopodes, de crustacés et autres. La consommation alimentaire journalière a été estimée à 0,91 % du poids corporel pour les juvéniles et 1,15 % du poids corporel pour les adultes[7]. Les phases métaboliques de l'hoplostèthe orange sont censées être liées aux variations saisonnières de l'abondance des proies. La phase inactive permet d'économiser leur énergie pendant les périodes de vaches maigres[8],[9].

L'hoplostèthe orange est océanodrome : il effectue des migrations de plusieurs centaines de kilomètres entre le lieu de ponte et les aires d'alimentation chaque année, mais il n'existe aucune preuve directe de ces migrations. Des preuves indirectes sont données par le pourcentage de femelles reproductrices au sein d'un banc[10]. Il forme de grandes agrégations lors de la période du frai (parfois séparées selon le sexe) durant laquelle les poissons libèrent des œufs sphériques (2,25 mm de diamètre), dans une substance huileuse orange-rouge, et le sperme directement dans l'eau. Les œufs fécondés (et plus tard les larves) sont planctoniques, remontent à environ 200 mètres de profondeur ; puis les alevins redescendent dans des eaux plus profondes à mesure qu'ils grandissent. L'hoplostèthe orange est également synchrone, l'excrétion du sperme et des œufs se fait simultanément. Le temps entre la fécondation et l'éclosion est estimé entre 10 et 20 jours ; la fécondité est faible, avec chaque femelle ne produisant que 22 000 œufs par kilogramme de poids corporel, ce qui est inférieur de 10 % à la moyenne des autres espèces de poissons. En outre, la ponte peut durer jusqu'à 2-3 semaines et commence autour de juin ou juillet. La croissance de l'hoplostèthe orange est très lente ; il n'atteint sa maturité sexuelle qu'entre 20 et 30 ans[11]. Son faible taux de croissance s'explique probablement par un taux de prédation faible et la rareté des proies dans les grandes profondeurs[9]. Il fait partie des espèces caractérisées par leur sénescence négligeable[12]. L’individu le plus âgé observé avait 149 ans, âge calculé par datation radiométrique des isotopes de ses otolithes[2],[13].

L'hoplostèthe orange vit à des profondeurs allant d'une centaine de mètres à près de 2 000 mètres, mais il est couramment pêché entre 900 et 1 800 mètres. Il fréquente le milieu et le bas du talus continental et les dorsales océaniques. La température de son environnement est comprise entre 4 et 7 °C. Il fréquente les récifs coralliens d'eau froide, où il trouve refuge[14].

On le trouve dans les eaux du monde entier, mais surtout dans l'océan Atlantique, l'océan Indien et l'océan Pacifique. Dans l'océan Pacifique occidental, dans l'est de l'océan Atlantique (à partir de l'Islande jusqu'au Maroc, et de la Namibie jusqu'à l'Afrique du Sud), dans l'Indo-Pacifique (au large de la Nouvelle-Zélande, de l'Australie) et au large du Chili, dans le Pacifique oriental[8],[15].

Hoplostethus provenant du grec ancien, construit à partir de 'όπλον' (hoplo) signifiant « arme » et de 'στῆθος' (stêthos) signifiant « poitrine ». Atlanticus fait référence à l'océan Atlantique où les premiers spécimens ont été pêchés[6]. Le terme hoplostèthe est donc une francisation du nom scientifique du genre Hoplostethus[16]. Mais le second « h » n'ayant pas une utilité phonétique, il est souvent enlevé, ce qui donne « hoplostète »[15].

Le terme « poisson-montre » est issu de l'apparence de la tête du poisson. Elle est ronde et dispose de nombreux canaux muqueux apparents, rappelant les rouages d'une montre. Son nom commercial « empereur » a été instauré dans les années 1980 avec la commercialisation de ce poisson[17].

L'hoplostèthe orange fut décrit pour la première fois par Robert Collett en 1889 sous le nom Hoplostethus atlanticus[15]. Depuis, le taxon n'a pas changé, cependant certains auteurs orthographient « atlanticum » au lieu de « atlanticus »[6].

Ce taxon connaît quelques synonymes :

L'hoplostèthe orange est très commun et sa chair est réputée délicieuse. Il fait l'objet d'une pêche importante au large de l’Europe occidentale, et aussi mais surtout au Sud de l'Australie et de la Nouvelle-Zélande. Bien que déjà consommé en Nouvelle-Zélande dès les années 1960, l'empereur a commencé à être pêché massivement par d'autres pays à partir des années 1980, époque où de grands bancs ont été découverts au-dessus des guyots et autres monts sous-marins. Dans les années 1990, les prises atteignaient 50 000 tonnes par an[9]. Les pêcheurs industriels ont commencé à prendre des centaines de tonnes par jour, provoquant une dangereuse chute des stocks. En effet ce poisson, aux effectifs de dédoublement supérieurs à 14 ans, pourrait bien disparaître rapidement si une pêche excessive continue à se pratiquer. Un moratoire sur la pêche de ce poisson pourrait être créé chez les pays concernés par cette surpêche[18].

L'âge de maturation utilisé dans les évaluations des stocks varie entre 23 et 40 ans, ce qui limite la vitesse du recrutement, étant donné que chaque nouvelle génération prend beaucoup de temps pour commencer la ponte[14].

Toutes les espèces de grand fond se reproduisent très tardivement et sont exposées à la surexploitation et la surpêche.

Une étude a montré dans les années 1990 (à l'ouest de l'Angleterre) sur des poissons vivant en profondeur en bordure du plateau continental que la réduction de leur biomasse à la suite de la pêche au chalut se fait très rapidement (en quelques années), mais d'une manière plus ou moins marquée selon d'espèce (dans ce cas par exemple l'hoplostèthe orange a plus rapidement et fortement décliné que le grenadier de roche coryphaenoides rupestris[19]

Les mesures de conservation consistent à appliquer des limites de capture, et d'inscrire les diverses espèces menacées d'extinction sur des listes tenues par les gouvernements et les associations environnementales. Selon la Seafood Watch (États-Unis), la Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society of New Zealand, la Marine Conservation Society (Royaume-Uni), les consommateurs devraient fortement éviter cette espèce. L'hoplostèthe orange est l'espèce la plus pêchée en Nouvelle-Zélande, il représente 17,2 % du total des exportations de poissons. Lorsque la biomasse d'origine est arrivé à 30 %, les quotas ont été fixés. Le rendement maximal durable a été fixé à 1 200 tonnes par an, mais en 2005, ce quota a été jugé trop élevé[20].

En 2010, Greenpeace International a ajouté l'hoplostèthe orange à sa liste rouge, qui contient des poissons qui font l'objet d'une pêche non-durable[21],[22].

La chair de l'hoplostèthe orange est ferme avec une douce saveur ; il est vendu en filets sans peau, frais ou congelés. En raison de sa longévité, il bioaccumule de grandes quantités de mercure dans ses tissus[23]. Sa consommation régulière peut avoir des effets néfastes sur la santé[24].

Hoplostethus atlanticus

L'hoplostèthe orange, hoplostèthe rouge ou poisson-montre (Hoplostethus atlanticus) est une espèce de poissons de la famille des Trachichthyidae. L'hoplostèthe orange vit dans tous les océans entre 900 et 1 800 m de profondeur. Il a une longévité potentielle d'au moins 149 ans et il n'atteint sa maturité sexuelle qu'entre 20 et 30 ans. Avec une longueur maximale de 75 cm pour 7 kg, c'est le plus grand de sa famille.

Commercialisé sous le nom d'empereur, il fait l'objet d'une importante exploitation commerciale, mais en raison de son faible recrutement, ses populations tendent à diminuer. De nombreux stocks, en particulier ceux de la Nouvelle-Zélande et de l'Australie, qui ont été exploités dans les années 1970, ont déjà été décimés ; les stocks de substitution récemment découverts s'épuisent rapidement.

Hoplostethus atlanticus (Collet, 1889), comunemente conosciuto come pesce specchio atlantico o pesce specchio[1]) è un pesce d'acqua salata appartenente alla famiglia Trachichthyidae.

Il pesce specchio atlantico è diffuso nell'oceano Atlantico, nell'Indiano, nel Pacifico occidentale. Non vive nel mar Mediterraneo. Vive sulla scarpata continentale o sulla piana abissale a profondità da 180 a 1809 metri[2].

La testa è molto grande e tozza, ricca di pieghe e ossa sporgenti, la bocca è girata verso l'alto, dotata di piccoli denti disposti in file. Il corpo è ovaloide, molto compresso ai fianchi, con peduncolo caudale allungato. Le pinne sono arrotondate, rette da grossi raggi. La pinna caudale è bilobata.

La livrea è molto semplice: tutto il corpo è rosso, con sfumature che variano dall'arancio al rosso carminio. L'interno della bocca e delle branchie è bluastro[2].

Raggiunge una lunghezza massima di 75 cm per 7 kg, più comunemente la taglia arriva a 40 cm[2].

È uno dei pesci ossei dalla vita più lunga: sono stati pescati esemplari di 149 anni[2].

La biologia della specie è poco nota, si crede che i giovanili vivano in acque profonde. L'accrescimento è molto lento[2].

H. atlanticus si nutre di crostacei (anfipodi, eufausiacei e gamberetti), cefalopodi e di pesci. Gli esemplari giovanili predano piccoli crostacei[2].

È preda abituale di Ruvettus pretiosus, Diastobranchus sp. e Merluccius merluccius[3].

Ha una notevole importanza per la pesca commerciale in certe aree. Nel 2006 è stata dichiarata specie minacciata dal governo australiano a causa della sovrapesca[2].

Hoplostethus atlanticus (Collet, 1889), comunemente conosciuto come pesce specchio atlantico o pesce specchio) è un pesce d'acqua salata appartenente alla famiglia Trachichthyidae.

De keizerbaars of oranje zaagbuikvis (Hoplostethus atlanticus) is een straalvinnige vis uit de familie van zaagbuikvissen (Trachichthyidae) en behoort derhalve tot de orde van slijmkopvissen (Beryciformes).

Het lichaam is oranjerood. Hij heeft een grote stompe kop en kaken met kleine, in stroken bijeen geplaatste tanden. De vis kan maximaal 75 cm lang worden.

Hoplostethus atlanticus is een zoutwatervis. De vis prefereert een diepwaterklimaat en heeft zich verspreid over de drie belangrijkste oceanen van de wereld (Grote, Atlantische en Indische Oceaan) aan de randen van het continentaal plat en op de diepzeebodem. De diepteverspreiding is 180 tot 1809 m onder het wateroppervlak.

Hoplostethus atlanticus is voor de visserij van groot commercieel belang. In de hengelsport wordt er weinig op de vis gejaagd. Omdat de soort lang leeft, traag volwassen wordt en relatief weinig nakomelingen heeft, is ze erg kwetsbaar voor overbevissing.

De keizerbaars of oranje zaagbuikvis (Hoplostethus atlanticus) is een straalvinnige vis uit de familie van zaagbuikvissen (Trachichthyidae) en behoort derhalve tot de orde van slijmkopvissen (Beryciformes).

Gardłosz atlantycki[potrzebny przypis] (Hoplostethus atlanticus) – gatunek ryby z rodziny gardłoszowatych (Trachichthyidae).

Zamieszkuje głębokie wody, poniżej stoku kontynentalnego, grzbiety i rowy oceaniczne ok. 800 do 1800 m p.p.m. Występuje we wszystkich oceanach z wyjątkiem Arktycznego.

Młode żywią się skorupiakami, dorosłe także rybami. Bardzo ceniony i ekskluzywny przysmak.[potrzebny przypis] Poławiane włokami dennymi na stokach oceanicznych w okolicach Nowej Zelandii i Australii przez cały rok, na północno-zachodnim Atlantyku od stycznia do marca.

Rośnie bardzo wolno, dorasta do 60 cm, maksymalnie do 75 cm, żyje do 150 lat[6].

Gardłosz atlantycki[potrzebny przypis] (Hoplostethus atlanticus) – gatunek ryby z rodziny gardłoszowatych (Trachichthyidae).

Hoplostethus atlanticus Collett, 1889, conhecido pelo nome comum de peixe-relógio, é um peixe do oceano profundo pertencente à família Trachichthyidae (traquictiídeos), distribuída pelo leste e noroeste do Oceano Atlântico, pelo sul do Oceano Pacífico e pelo Oceano Índico.[2]

Apesar de existirem referências à captura de espécimes de maior dimensão, a espécie tem um comprimento máximo aproximado de 40 cm.[3] Na barbatana dorsal tem de 4 a 6 espinhas e 15 a 19 raios flexíveis, enquanto que na barbatana anal tem 3 espinhas e 10 a 12 rios flexíveis. A cor é vermelho alaranjado, brilhante, com as cavidades da boca e guelras de cor azulada[3] .

É um peixe batipelágico e oceanódromo, que vive sedentário junto ao substrato a uma grande profundidade, normalmente entre 400 e 900 m,[4] normalmente nas águas frias do talude continental, nas cordilheiras oceânicas e outros relevos altos marinhos, onde vive disperso, alimentando-se de crustáceos e de outros peixes[2] .

O crescimento é muito lento, sendo um dos peixes mais longevos conhecidos, com um espécimen capturado com uma idade de 149 anos.[5] Sabe-se pouco sobre as suas larvas e juvenis, que habitam provavelmente em águas abissais.[6]

A espécie é alvo de uma importante pescaria comercial, sendo amplamente comercializada na Austrália, Japão, Nova Zelândia, Europa e América do Norte[2] , fresco ou congelado, sendo consumido frito ou assado.[7] Os barcos de pesca localizam esporadicamente densos cardumes da espécie.

|acessodata= (ajuda)

Hoplostethus atlanticus Collett, 1889, conhecido pelo nome comum de peixe-relógio, é um peixe do oceano profundo pertencente à família Trachichthyidae (traquictiídeos), distribuída pelo leste e noroeste do Oceano Atlântico, pelo sul do Oceano Pacífico e pelo Oceano Índico.

Atlantisk soldatfisk (Hoplostethus atlanticus) är en djuphavsfisk som framför allt lever utanför Atlantens kuster, men också i Stilla havet och Indiska oceanen. Den kallas också atlantsoldatfisk.[2]

Den atlantiska soldatfisken är orangeröd med flera slemfyllda gropar på huvudet.[2] Största längd är 75 cm, även om den vanligen inte blir mycket längre än 40 cm.[3] Den kan leva upp till en uppskattad ålder av 149 år,[3] som har tagits fram genom radiologisk undersökning av en hörselsten[4]. Det är sällan fisken blir så gammal; de större exemplaren brukar vara omkring 75 år gamla.[2]

Arten är en djuphavsfisk som lever på ett djup mellan 300 och 1 700 m, där den lever av fisk, bläckfisk och räkor.[2] Litet är känt om dess fortplantning[3], men den blir könsmogen vid ungefär 35 års ålder.[5]

Arten lever i västra Stilla havet, östra Atlanten från Island till Marocko och från Namibia till Sydafrika, västra Atlanten utanför Nova Scotia, södra centrala Indiska oceanen till vattnen utanför utanför Nya Zeeland och Australien samt i östra Stilla havet utanför Chile.[3]

Arten fiskas flitigt utanför Nya Zeeland och södra Australien.[2] På grund av kraftigt överfiske förklarades den för hotad av den australiska regeringen 2006[3], och WWF avråder från konsumtion av den.[5].

Atlantisk soldatfisk avbildad av Astrid Andreasen den 7 Feb 1994 på ett frimärke från Färöarna.

Atlantisk soldatfisk (Hoplostethus atlanticus) är en djuphavsfisk som framför allt lever utanför Atlantens kuster, men också i Stilla havet och Indiska oceanen. Den kallas också atlantsoldatfisk.

Cá tráp cam (Danh pháp khoa học: Hoplostethus atlanticus) là một loài cá biển trong họ Trachichthyidaetrong tiếng Anh nó còn được gọi là Orange Roughy. Loài cá Hoplostethus atlanticus bị cạn kiệt về số lượng do nạn khai thác quá mức. Các chuyên gia nói rằng phải mất nhiều thập kỉ mới khôi phục được số lượng loài này lại như cũ.

Loài cá biển sâu ngày càng là những món đặc sản bị khai thác nặng nề, chủ yếu là do con người thiếu cá ngừ để bắt và ăn vì thế hiện naybuộc phải ăn những phiên bản cá đột biến kỳ dị. Nó không phải là con cá bình thường đã bị tra tấn bằng cách lột da khi còn sống. Chúng ta ăn thịt của con cá này, nhưng khi chúng còn sống, đó là một trong những con cá bị săn đuổi nhất. Các đầu bếp thích Orange Roughy, giống như những loài cá biển sâu khác, ít nhất là 100 tuổi vì vòng đời của nó rất nhậm.

Cá tráp cam (Danh pháp khoa học: Hoplostethus atlanticus) là một loài cá biển trong họ Trachichthyidaetrong tiếng Anh nó còn được gọi là Orange Roughy. Loài cá Hoplostethus atlanticus bị cạn kiệt về số lượng do nạn khai thác quá mức. Các chuyên gia nói rằng phải mất nhiều thập kỉ mới khôi phục được số lượng loài này lại như cũ.

Hoplostethus atlanticus Collett, 1889

Атлантический большеголов, или атлантический слизнеголов, или исландский берикс[1] (лат. Hoplostethus atlanticus) — вид крупных глубоководных лучепёрых рыб семейства большеголовых (Trachichthyidae). По сведениям Общества охраны моря (Marine Conservation Society), является видом, находящимся под угрозой[2].

Атлантический большеголов живёт в холодной воде (от 3 до 9 °C) на глубине от 180 до 1800 метров в Атлантическом, Тихом и Индийском океанах. Известен большой продолжительностью жизни. Максимальный зафиксированный (хотя и поставленный под сомнение) возраст — 149 лет. Является объектом глубоководной траулерной рыбной ловли. При жизни имеет красновато-кирпичный цвет, после смерти — желтовато-оранжевый. Рост очень медленный, созревание позднее.

Атлантический большеголов, или атлантический слизнеголов, или исландский берикс (лат. Hoplostethus atlanticus) — вид крупных глубоководных лучепёрых рыб семейства большеголовых (Trachichthyidae). По сведениям Общества охраны моря (Marine Conservation Society), является видом, находящимся под угрозой.

大西洋胸棘鯛是胸棘鯛屬的一種,分布於全球各大洋熱帶至溫帶海域,棲息深度180-1809公尺,體長可達75公分,棲息在大陸坡、海脊等深水域,屬肉食性,以魚類、甲殼類、片腳類等為食,可做為食用魚。

大西洋胸棘鯛的大規模商業捕撈始於1970年代,但由於過度捕撈,其數量迅速下降。現在新西蘭是這種魚的主要產地,現在絕大多數大西洋胸棘鯛都是在此捕撈的。[1]

大西洋胸棘鯛是胸棘鯛屬的一種,分布於全球各大洋熱帶至溫帶海域,棲息深度180-1809公尺,體長可達75公分,棲息在大陸坡、海脊等深水域,屬肉食性,以魚類、甲殼類、片腳類等為食,可做為食用魚。

大西洋胸棘鯛的大規模商業捕撈始於1970年代,但由於過度捕撈,其數量迅速下降。現在新西蘭是這種魚的主要產地,現在絕大多數大西洋胸棘鯛都是在此捕撈的。

オレンジラフィー(学名:Hoplostethus atlanticus )は、ヒウチダイ科の魚類である。

左右が平たい体型をしている。最大は55センチメートル程度。頭部の皮膚は多孔性である。

水深100メートルから1500メートルくらいの深海に生息している底生魚である。

食用の高級白身魚として欧米や現地で食されている。 オーストラリアやニュージーランドでは重要な水産物の一つでもある。ニュージーランドでは1980年代に輸出品目として深海魚に注目が集まり、チャタム諸島に好漁場が見つかった事から乱獲された。一般的に深海魚の成長性及び再生産性は高くないため、1990年代には漁獲量が制限される事態になるなど資源としての持続性の維持には注意が必要となる。

皮下には消化出来ない脂(ワックスエステル)を蓄えているため食用においてはこの部分を切り落とす必要がある。 このワックスエステルは精製されオレンジラフィー油として化粧品などに利用されており、医薬部外品原料規格においても「オレンジラフィー油」として登録されるなど日本国内では食用よりもオレンジラフィー油の方が馴染み深い魚と思われる。

オレンジラフィー(学名:Hoplostethus atlanticus )は、ヒウチダイ科の魚類である。

오렌지라피의 머리는 둥글다. 1개의 등지느러미에는 4~6개의 등뼈와 15~19개의 연조가 들어있다. 항문지느러미에는 3개의 등뼈와 10-12개의 연조가 있다. 19-25개의 복부 모비늘은 지느러미와 항문 사이에 딱딱한 골반 중간 능선을 형성한다. 가슴지느러미는 각각 15-18개의 연조를 포함한다. 골반지느러미는 흉부에 있으며 1개의 등뼈와 6개의 연조를 포함한다. 꼬리지느러미는 갈라진다. 입과 아가미 구멍의 내부는 푸르스름한 검은색이다. 입 자체는 크고 크게 기울어져 있다. 비늘은 딱딱하고 끈적거린다. 오렌지라피의 눈은 크다.

오렌지라피의 최대 표준 몸길이는 75cm이고 최대 몸무게는 7kg이다.