en

names in breadcrumbs

Golden poison frogs are best known for their extremely potent poison. The toxins they produces are twenty times more powerful than any other poison dart frog toxin. Their brightly colored bodies warn predators of their extreme toxicity. This serves as the frog’s main anti-predator adaptation. The toxins produced are steroidal alkaloids batrachotoxin, homobatrachotoxin, and batrachotoxinin A. These compounds are extremely potent modulators of voltage-gated sodium channels. They keep the channels open and depolarize nerve and muscle cells irreversibly. This damaging action may lead to arrhythmias, fibrillation, and eventually cardiac failure. When accidentally transferred onto human facial skin, these toxins have been reported to cause a burning sensation lasting several hours.

There is only one known predator of P. terribilis: Liophis epinephelus. This is a small snake that feeds on young frogs. The snake is immune to the toxins produced by golden poison frogs but since it is so small, it can only feed on juvenile frogs.

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: aposematic

Golden poison frogs are the most highly toxic of all frogs. Colombian tribes, such as the Embre and Choco Indians, use poison secreted from the frogs’ skin to poison their blowgun darts. After heating darts over a fire, they are wiped over the frogs’ backs. Heat causes the back of the frog to moisten with poison which makes it easily accessible. Poisoned darts can stay lethal for up to two years. The toxin enables these tribes to catch small animals for food. These frogs are also being captured, bred, and sold as pets. This is possible because of their decrease in toxicity once held in captivity for a certain period of time. Medical research is also being done to see if these poisons can be developed into muscle relaxants, anesthetics, and heart stimulants. It is thought that it could even become a better anesthetic than morphine.

Positive Impacts: pet trade ; body parts are source of valuable material; source of medicine or drug ; research and education; controls pest population

Golden poison frogs have a variety of bright vibrant colors that cover their entire bodies, from mint green to yellow to orange and sometimes white. Yellow or deep yellow, is the most common color seen, giving them their common name. Phyllobates terribilis is the most toxic species of frog. Unlike most other members of the Family Dendrobatidae, Phyllobates terribilis has uniform body coloration, rather than dark spots and stripes, as in their relatives Phyllobates aurotaenia , Phyllobates lugubris and Phyllobates vittatus. Adults are more brightly colored than young, which have the same primitive pattern of most other members of the family Dendrobatidae. They have dorsolateral stripes on dark bodies until they mature. By the time they reach adulthood, their coloration has changed to a single bright color.

An easy way to identify these frogs is by the odd protrusion from their mouth. This gives the false illusion that these frogs have teeth. Instead, they have an extra bone plate in their jaw that projects outwards and gives the appearance of teeth. These frogs have three toes on each foot. Each outside toe is almost equal in length but the middle toe is longer than the other two.

Bright skin coloration in P. terribilis is thought to be a warning to predators that they are poisonous. Their skin is saturated in an alkaloid poison that contains batrachotoxins. These toxins prevent nerves from transmitting nerve impulses and ultimately result in muscle paralysis. About 1900 micrograms of batrachotoxins can be found in these frogs. Only 2 to 200 micrograms is thought to be lethal to humans.

Adult females are typically larger than males. The average body length reaches 47 mm but females can reach 50 to 55 mm. Compared to the 175 species of dendrobatids, P. terribilis does not have a wide range of sizes. Other species can be as small as a human fingernail.

Range length: 47 to 55 mm.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry ; poisonous

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger

In the wild golden poison frogs are believed to live up to 5 years or more. Due to their high toxicity levels, these frogs have few predators, contributing to their long lifespan. Lifespan in the wild has not been confirmed because these frogs have only been observed in captivity, where they have lived up to 5 years old.

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 5 (high) years.

Typical lifespan

Status: captivity: 5 (high) years.

Golden poison frogs thrive in lowland Amazonian rainforests. This an extremely humid region that receives up to 5 m of rain per year and a minimum of 1.25 m. The region they inhabit is characterized by a hilly landscape, elevations varying from 100 to 200 m, and is covered by areas of wet gravel and small saplings and relatively little leafy debris. They are terrestrial animals that live on the forest floor, but they rely on freshwater to support their young.

Range elevation: 100 to 200 m.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: rainforest

Aquatic Biomes: temporary pools

Phyllobates terribilis is found in the Amazonian rainforest along the Pacific coast of Colombia. Other members of the Family Dendrobatidae have been found in close proximity along the coast of South America into the southern part of Central America. Phyllobates terribilis population is concentrated along the upper Rio Saija drainage in the vicinity of Quebrada Guangui’ and at La Brea in Colombia. Geographically isolated populations exist along the east and west banks along this river, dividing the population. Overall P. terribilis has a limited range, but is abundant within that area.

Biogeographic Regions: neotropical (Native )

Golden poison frogs are insectivores and prey primarily on species of Brachymyrmex and Paratrechina ants. They also consume small invertebrates such as termites and beetles. Golden poison frogs use their long, sticky tongues to capture prey. They stalk and attack prey in one quick movement; this movement is so fast it's hard to see the mechanics of it with the naked eye. An adhesive tongue enables the prey to stick to its mouth to aid in capturing. Typically, they will not attack an insect bigger than a full grown cricket, approximately 1 inch. It has recently been discovered that feeding on a small Choresine beetle (Family Melyridae) may be the main source of toxicity for P. terribilis.

Animal Foods: insects; terrestrial non-insect arthropods; terrestrial worms

Primary Diet: carnivore (Insectivore , Vermivore)

Golden poison frogs have only one natural predator. They usually sit out in the open. When approached they do not try to hide, but rather further their distance from the thing that approaches it. They are generalist feeders, preying on all types of fruit flies, crickets, beetles, and termites. Recent research shows that these frogs may obtain some of their poison by eating a beetle that belongs to the family, Melyridae.

Golden poison frog males engage females in courtship by singing a long, melodious trill. This trill lasts 6 to 7 seconds followed by a 2 to 3 second version. The trill is usually a uniform train of notes uttered at a rate of 13 beats per second. The frequency for this tune is 1800Hz. This is a lower frequency when compared to related species of the family Dendrobatidae. They also communicate through gestures. A push up movement of the body represents dominance while the lowering of the head implies submission. A sign of excitement usually seen during hunting and courting includes the tapping of their long middle toe.

Communication Channels: visual ; acoustic

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic

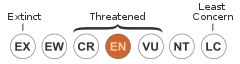

Golden poison frog populations have been decreasing due to deforestation for agricultural purposes. They can be found in fewer than five areas. This species is listed as endangered according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: endangered

Like most frogs, golden poison frogs go through complete metamorphosis. Eggs are laid in small clutches of less than 20 and carried on the backs of males to small pools of water, where they develop and metamorphose into froglets.

Development - Life Cycle: metamorphosis

Golden poison frogs do not display aggressive behavior towards humans. However, contact with their skin can prove fatal because of their extreme toxicity. This is not true of captive individuals, which tend to lose their toxicity in the absence of the wild prey that are the source of that toxin.

Negative Impacts: injures humans (poisonous )

Phyllobates terribilis is polygynandrous; both males and females have multiple mates. Courtship and egg laying have only been observed in captivity, with limited specimens. Each breeding involved two or more male frogs and one female. Males attract females by using a variety of high pitched calls. Mating could be described as a frantic frenzy where individuals move quickly around each other during egg laying. This is hard to observe because the movement is so fast and done under cover of vegetation. Specifics on mode of reproduction are unconfirmed but it is believed that there is some vent to vent contact between frogs during copulation. However, golden poison frog mating rituals have not been observed in their natural habitat. Golden poison frogs are thought to mate year round.

Mating System: polygynandrous (promiscuous)

Golden poison frog eggs have not been found in the wild. In captivity, clutches of eggs usually do not exceed 20. In captivity, once eggs are laid and fertilized in water (by captive carers) they hatch 11 to 12 days later, typically taking 2 to 4 days for all the eggs to be completely hatched. Not even 10 days after leaving the water, they begin to feed on Drosophila flies.

Breeding interval: Breeding intervals are unknown.

Breeding season: Golden poison frogs seem to breed year round.

Range number of offspring: 8 to 18.

Average number of offspring: 13-14.

Range time to hatching: 11 to 12 days.

Range time to independence: 55 to 60 days.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 12 to 18 months.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 13 months.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 12 to 18 months.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 13 months.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; year-round breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization (External ); oviparous

In the wild, once the female lays the eggs, the male fertilizes them and attaches them to its back. Only three male frogs have been captured with clutches of eggs on their backs. It seems that this period of carrying tadpoles on their backs is brief. It is a method of getting the eggs from their laying and fertilization site to the water to hatch. After fertilization and transfer to a small area of water for development, there is no further parental care.

Parental Investment: pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Male)

La granota de punta de fletxa daurada[1] (Phyllobates terribilis) és una granota amb un dels verins més letals del món animal. El seu verí pot causar la mort a 20.000 ratolins de laboratori.[2] El seu hàbitat són les selves humides a la costa del Carib de Colòmbia. Pot arribar a fer tan sols 5 cm; el seu color és groc or metàl·lic, en els dits dels peus té uns discos que l'ajuden a subjectar-se a les plantes.

N'hi ha dues variacions de color de la qual se separa una subespècie: Phyllobates terribilis i Phyllobates terribilis mint. P. terribilis de vegades es confon amb l'espècie Dendrobates truncatus, que té la franja verda en les potes posteriors, cosa que no ocorre amb P. terribilis. Les seves preses són insectes com formigues, tèrmits i diminuts escarabats.

El seu verí (batratoxina) és un dels més potents del regne animal. Encara que hi ha altres animals que també tenen batratoxina, en aquesta granota la seva concentració és molt alta. Els indígenes utilitzen el verí d'aquesta perillosa granota per a caçar les seves preses impregnant les armes, com llances i fletxes.

Aquesta espècie es troba amenaçada d'extinció, ja que el seu únic hàbitat és la selva humida i aquesta s'està desforestant ràpidament; a més, són animals amb poca tolerància a la contaminació.

La granota de punta de fletxa daurada (Phyllobates terribilis) és una granota amb un dels verins més letals del món animal. El seu verí pot causar la mort a 20.000 ratolins de laboratori. El seu hàbitat són les selves humides a la costa del Carib de Colòmbia. Pot arribar a fer tan sols 5 cm; el seu color és groc or metàl·lic, en els dits dels peus té uns discos que l'ajuden a subjectar-se a les plantes.

N'hi ha dues variacions de color de la qual se separa una subespècie: Phyllobates terribilis i Phyllobates terribilis mint. P. terribilis de vegades es confon amb l'espècie Dendrobates truncatus, que té la franja verda en les potes posteriors, cosa que no ocorre amb P. terribilis. Les seves preses són insectes com formigues, tèrmits i diminuts escarabats.

El seu verí (batratoxina) és un dels més potents del regne animal. Encara que hi ha altres animals que també tenen batratoxina, en aquesta granota la seva concentració és molt alta. Els indígenes utilitzen el verí d'aquesta perillosa granota per a caçar les seves preses impregnant les armes, com llances i fletxes.

Aquesta espècie es troba amenaçada d'extinció, ja que el seu únic hàbitat és la selva humida i aquesta s'està desforestant ràpidament; a més, són animals amb poca tolerància a la contaminació.

Pralesnička strašná (Phyllobates terribilis) či pralesnička zlatá je malá, zelená nebo žlutě až oranžově zbarvená žába z čeledi pralesničkovitých.

Pralesnička strašná je největší z druhů šípových žab a může v dospělosti dorůst až 55 mm, přičemž samice jsou typicky větší než samci. Stejně jako všechny šípové žáby jsou dospělci pestře vybarvení, avšak postrádají tmavé skvrny, jež jsou charakteristické pro příbuzné druhy. I tak slouží jako zbarvení výstražné, varující před jejich jedovatostí. Na prstech má přilnavé polštářky, které jí pomáhají při šplhání po rostlinách. Ve spodní čelisti má také kostěnou destičku, která vzhledem připomíná zuby a je jejím charakteristickým znakem odlišujícím ji od ostatních žab tohoto rodu.

Phyllobates terribilis se vyskytuje ve třech různých barevných variacích:

Kůže pralesničky strašlivé je nasycena alkaloidním jedem, jenž je jedním z jedů běžných u šípových žab (batrachotoxiny). Ty zabraňují nervům v přenášení impulsů a zanechávají svaly v neaktivním stavu smrštění, což může vést k selhání srdce nebo fibrilaci. Alkaloidní batrachotoxiny mohou žáby uchovávat i celé roky poté, co žába přijde o zdroj jedu v potravě, poněvadž jed se neodbourává rychle, a to ani poté, co je přemístěn na jiný povrch. Je známo, že drůbež a psi uhynuli poté, co pouze prošli po papírové utěrce, jež byla jedem napuštěna.

Průměrná dávka jedu, kterou má žába k dispozici, je proměnlivá v různých lokacích a liší se i podle druhu potravy. Běžná pralesnička mívá kolem jednoho miligramu jedu, což stačí k zabití 10 000 myší. Taková dávka může zabít deset až dvacet lidí nebo dva samce slona afrického a odpovídá tak množství 15 tisíc lidí na gram. Tato neobyčejně jedovatá látka je velmi vzácná - batrachotoxin lze nalézt jen u tří druhů jedovatých žab v Kolumbii (všechny druhu phyllobates) a tří druhů jedovatých ptáků na Papui Nové Guineji (jedná se o druhy Pištec černohlavý, Pištec proměnlivý a Kosovec šoupálčí). Příbuznými jedy jsou histrionicotoxin a pumiliotoxin, které se vyskytují u rodu dendrobates.

Jako většina ostatních jedovatých žab uchovává i pralesnička strašná svůj jed v kožních žlázách a díky němu jsou odporné pro predátory. Zabije prakticky cokoli, co ji může sežrat kromě hada liophis epinephelus, jenž je proti jedu rezistentní, nikoli však imunní. Pralesnička strašná tak má jen dva nepřátele: tohoto žabožravého hada a indiány z kmene Choco, kteří používají její jed k otrávení špiček šípů do foukaček. Jed získávají tak, že žáby napíchnou na špičatou hůlku a pak ji zahřívají nad ohněm. Přitom se uvolňují kapky jedu, které indiáni zachycují do nádobek, kde následně namáčejí šipky. Kořist zasažená jedovatou šipkou zemře do několika sekund. Člověk prý podle indiánů uběhne ještě několik desítek metrů a pak padne mrtev k zemi.

Jed žába neumí produkovat sama a ani jej nepoužívá k zabíjení kořisti jako to dělají například hadi. Pro pralesničku je jed pouze obranným mechanismem. Jediní tvorové, kteří jedu pralesniček zcela odolají, jsou samy jedovaté žáby. Batrachotoxin napadá sodíkové kanály buněk, ale tyto žáby mají kanály speciální, kterým jed uškodit nemůže.

Jelikož snadno dostupná potrava jako octomilky a malí cvrčci neobsahují moc alkaloidů potřebných k produkci batrachotoxinů, v zajetí jich žáby nemají dostatečné množství a nakonec o toxicitu přicházejí. Mnozí amatérští chovatelé a herpetologové líčili, že žáby v zajetí odmítají žrát mravence, přestože mravenci tvoří velkou část potravy divokých žáb. Příčinou toho bude nejspíše fakt, že nejsou jako potrava dostupné přesné druhy mravenců, které žáby v přírodě loví. Ačkoli při chovu v zajetí žáby ztrácejí jedovatost, pokud nemají dostatek potravy potřebné pro výrobu jedu a v zajetí narozené žáby se rodí zcela neškodné, žába odchycená v přírodě dokáže jed uchovávat celé roky. Není jasné, který z lovených druhů poskytuje účinný alkaloid, jenž žáby činí tak výjimečně jedovatými, ani zda žáby modifikují jiný dostupný toxin tak, aby vyráběly ještě efektivnější variantu tak, jako to dělají jejich příbuzné rodu dendrobates.

Tak vysokou toxicitu žáby zřejmě mají díky konzumaci malých druhů hmyzu a dalších členovců. Některý z nich může být tím nejjedovatějším tvorem planety. Vědci se domnívají, že tím hlavním druhem hmyzu je možná malý brouček rodiny melyridae, z nichž minimálně jeden vyrábí toxin nalézaný u pralesničky strašné. Tyto druhy brouků také žijí v kolumbijských pralesích.

P. terribilis je považována za jednu z nejinteligentnějších žab. Jako všechny jedovaté žáby, i chovaná pralesnička strašná dokáže po několika týdnech rozpoznat své lidské opatrovníky. Jsou to také velmi šikovní lovci jazykem - svým dlouhým lepkavým jazykem kořist málokdy minou. Tato úspěšnost naznačuje lepší mozkovou kapacitu a kvalitnější rozlišování pomocí zraku, než jak je tomu u jiných žab. Pralesničky strašné jsou zvědavé, odvážné a zdá se, že jsou si i vědomy toho, že jsou takřka nezranitelné: nepokouší se nijak skrývat a spíše své barvy předvádějí, aby predátory zastrašily.

Jsou také velmi společenskými tvory. Divoké pralesničky obvykle žijí ve skupinách o čtyřech až sedmi jedincích; v zajetí mohou obývat společný prostor až po skupinách o 10 - 15 žabách, ačkoli společenství, která se rozrostou nad tento počet, snadno podléhají agresi a chorobám. Stejně jako všechny jedovaté žáby se i terrabilis mezi sebou málokdy chovají agresivně, rozmíšky mezi samci ve skupině se však vyskytují.

Vzájemně spolu komunikují - a to nejen voláním, ale také gesty, jelikož jsou vůči svému jedu imunní. Zvedají se, což je znakem dominance, kdežto hlava spuštěná dolů naznačuje podřízení. Ťukání dlouhým prostředníčkem, které lze často spatřit při lovu a dvoření, je známkou vzrušení.

Skupiny pralesniček strašných se kvůli páření shromažďují jednou až dvakrát ročně. Zatímco v jiných obdobích jsou samci velmi mírumilovní, když zápolí s ostatními o prostor k páření, dokáží být ohromně bojovní. Samičky zůstávají naproti tomu v klidu. Dvoření probíhá podobně jako u pralesničky batikové. Její volání se skládá z rychlých sérií vysoko posazeného pískání. Pralesničky strašné jsou během rozmnožování pozoruhodné svým častým hmatovým kontaktem, kdy každý z partnerů hladí při páření toho druhého na hlavě, bocích a kloakální oblasti.

Tyto pralesničky jsou též starostlivými rodiči. Vajíčka kladou na zem skryté pod listoví. Jakmile se pulci vyklubou, zanoří se do slizu na zádech rodičů, kteří pak mladé odnáší do vody, která se hromadí v broméliích. Pulci se tam pak živí řasami a larvami komárů, přičemž je matky dokrmují neoplodněnými vajíčky. Mohou se však krmit i jinou potravou a matku na dokrmování nevyžadují. Poté, co se z nich vyvinou žabky, rodiče je dovedou ke skupině, kde jeden z nich (většinou matka) žil předtím. Mladé celá skupina přijímá, ale až do pohlavní dospělosti zůstávají v blízkosti matky.

Stejně jako ostatní šípové žáby je i pralesnička strašná neškodná, pokud je chována stranou zdrojů své přirozené potravy. Ve viváriích jsou nejoblíbenějšími chovanci a je o něco snazší jim shánět potravu než pro jiné šípové žáby. Jako krmení se mohou používat větší octomilky, malí cvrčci, zavíječi a termiti, pokud se podávají s kalciem a jinými minerály. Teplota by se měla pohybovat od 21 do 25 °C. Na vysoké teploty jsou citlivé a vyžadují vysokou vlhkost, protože pocházejí z nejvlhčích pralesů na světě. Pralesničky strašné nejsou tak teritoriální jako příbuzné druhy a mohou se tedy chovat ve skupinách, je pro ně však kvůli jejich vzrůstu v dospělosti zapotřebí větších prostor. Půtky mezi žábami jsou běžné, zranění jsou však vzácná a neví se o usmrceních způsobených konflikty.

V tomto článku byl použit překlad textu z článku Golden Poison Frog na anglické Wikipedii.

Pralesnička strašná (Phyllobates terribilis) či pralesnička zlatá je malá, zelená nebo žlutě až oranžově zbarvená žába z čeledi pralesničkovitých.

Der Schreckliche Pfeilgiftfrosch (Phyllobates terribilis), auch als Schrecklicher Giftfrosch, Schrecklicher Blattsteiger, Gelber Blattsteiger, Goldener Giftfrosch, Zitronengelber Blattsteiger oder Goldener Blattsteiger bezeichnet, gilt als eines der giftigsten Tiere und als die giftigste Froschart. Sie wurden von den Chocó-Indianern Kolumbiens als Pfeilgiftfrösche benutzt, wie von anderen indigenen Völkern Südamerikas besonders giftige Arten der Familie Baumsteigerfrösche (Dendrobatidae), um mit ihrem Hautgift Blasrohrpfeile zu bestreichen. Tiere in Gefangenschaft verlieren ihr Gift, ihre Nachkommen sind ungiftig. Für die Synthese des Giftes (Batrachotoxin) werden Alkaloide spezieller tropischer Futterinsekten benötigt.[1][2]

Der Schreckliche Pfeilgiftfrosch wird bis zu fünf Zentimeter lang und zählt damit zu den größten Vertretern der Baumsteigerfrösche. Die Weibchen sind im Durchschnitt geringfügig größer als die Männchen. Der Körper ist einheitlich gelb, metallisch gelbgrün oder orange gefärbt, selten auch grau. Die Bauchseite und die Beine sind im Gegensatz zu anderen Phyllobates-Arten nur unwesentlich dunkler. Die Jungtiere sind anders gefärbt als die erwachsenen Exemplare. Sie sind schwarz mit zwei seitlichen Rückenstreifen.

Der Schreckliche Pfeilgiftfrosch kommt nur in einem sehr kleinen Areal um den Fluss Rio Saija nahe der Pazifikküste Kolumbiens im Department Cauca vor. Das Gebiet weist bis zu 200 m hohe Hügel auf. Die Frösche bewohnen dort den tropischen Regenwald und leben primär auf dem Waldboden und in Flussnähe. Sie sind außerhalb der Paarungszeit tagaktive Einzelgänger. Innerhalb des kleinen Verbreitungsgebietes soll die Bestandsdichte sehr hoch sein.

Die Männchen verfügen über Schallblasen, mit denen sie zur Fortpflanzungszeit trillernde Rufe erzeugen. Die Eier werden an Land abgelegt. Die schlüpfenden Larven werden von den Männchen auf den Rücken genommen und zu dauerhaft wasserführenden Gewässern transportiert, wo sie ihre Kaulquappenphase durchlaufen.

Die IUCN stuft Phyllobates terribilis unter anderem wegen des kleinen Verbreitungsareals als endangered (stark gefährdet) ein.

Der Schreckliche Pfeilgiftfrosch (Phyllobates terribilis), auch als Schrecklicher Giftfrosch, Schrecklicher Blattsteiger, Gelber Blattsteiger, Goldener Giftfrosch, Zitronengelber Blattsteiger oder Goldener Blattsteiger bezeichnet, gilt als eines der giftigsten Tiere und als die giftigste Froschart. Sie wurden von den Chocó-Indianern Kolumbiens als Pfeilgiftfrösche benutzt, wie von anderen indigenen Völkern Südamerikas besonders giftige Arten der Familie Baumsteigerfrösche (Dendrobatidae), um mit ihrem Hautgift Blasrohrpfeile zu bestreichen. Tiere in Gefangenschaft verlieren ihr Gift, ihre Nachkommen sind ungiftig. Für die Synthese des Giftes (Batrachotoxin) werden Alkaloide spezieller tropischer Futterinsekten benötigt.

தங்க நச்சுத் தவளை ( golden poison frog (Phyllobates terribilis),[1] இதன் வேறு பெயர்கள் golden frog, golden poison arrow frog, golden dart frog ) என்பது கொலொம்பியாவின் பசிபிக் கடற்கரைப் பகுதியல் காணப்படும் நச்சுத்தன்மைவாய்ந்த நச்சு அம்புத் தவளை வகையைச் சேர்ந்த ஒரு ஓரிடவாழி தவளையாகும். இவை ஆண்டு மழையளவு 5 மீ அல்லது அதற்கு மேற்பட்டுள்ளதாகவும், வெப்பநிலை குறைந்தது 26 ° செ என்ற அளவும், கடல் மட்டத்தில் இருந்து 100 மீட்டர் முதல், 200 மீட்டர் வரையும், ஈரப்பதம் 80-90% உள்ள மழைக் காடுகளில் காணப்படுகின்றன. இது ஒரு சமூக விலங்காகும், இவை ஆறு தவளைவரையிலான குழுக்களாக வாழுகின்றன. இந்த தவளைகள் பெரும்பாலும் சிறிய அளவுள்ளதாகவும், பிரகாசமான வண்ணங்கள் கொண்டதாகவும் தீங்கற்றதாகவும் கருதப்படுகிறது, ஆனால் காட்டு தவளைகள் நச்சுத்தன்மை கொண்டதாக உள்ளன.[2] இரண்டு அங்குலமே உள்ள இந்தத் தவளைதான் உலகிலேயே மிக அதிக நச்சு கொண்ட தவளை. ஒரு முறை நச்சை பீய்ச்சி அடித்தால் மூன்றே நிமிடங்களில் 10 மனிதர்களைக் கொன்றுவிடக்கூடியது. பத்து ஆயிரம் சுண்டெலிகளைக் கொன்றுவிடக் கூடியது. இவை பொன் நிறத்தில் மட்டுமின்றி, ஆரஞ்சு, வெளிர் பச்சை நிறங்களிலும் இவை காணப்படுகின்றன. தன் ஆபத்தானவன் என்று மற்ற விலங்குகளை எச்சரிப்பதற்காகவே இவ்வாறு கண்கவர் வண்ணங்கள் கொண்டுள்ளது. அழிந்துவரக்கூடிய அரிய உயிரினங்களின் பட்டியலில் இந்தத் தங்கத் தவளைகளும் உள்ளன. காடுகளை அழித்தல், சட்டத்துக்குப் புறம்பாகத் தங்கச் சுரங்கம் அமைத்தல், கோகோ பயிரிடுதல் போன்ற பல காரணங்களால் தங்கத் தவளைகள் அழிவின் விளிம்புக்குத் தள்ளப்பட்டுள்ளன.[3]

தங்க நச்சுத் தவளை ஓரிடவாழியாகும். இவை பசிபிக் கடற்கரையில் ஈரப்பதமான மழைக்காடுகள் உள்ள கொலொம்பியாவின் கவுகா மற்றும் வள்ளி டில் கவுகா ஆகிய பகுதிகளில்,[4] சுமார் 5,000 சதுர கிலோமீட்டர் பரப்பளவில் உள்ள காடுகளில் காணப்படுகிறது. இவை தரையில் முட்டைகளை இடுகின்றன. முட்டை பொரித்து வெளிவரும் தலைப்பிரட்டைகளை ஆண் தவளைகள் குளங்களுக்கு கொண்டுசென்று விடுகின்றன. [5]

இந்த தங்க நச்சுத் தவளைகள் ஆபத்தான உயிரினங்களே தவிர, கொடூரமான உயிரினங்கள் அல்ல. பொதுவாக நச்சுத்தன்மை கொண்ட விலங்குகளும் பூச்சிகளும் பற்கள், கொடுக்குகள் மூலம் நச்சை செலுத்துகின்றன. ஆனால், தங்கத் தவளை தனக்கு ஆபத்து என்று உணர்ந்தால், தன்னைக் காப்பாற்றிக்கொள்வதற்காகத் தோலில் இருந்து நச்சை பீய்ச்சி விடுகிறது. இந்தத் தவளையை நம் கையில் உறையில்லாமல் வைத்திருந்தால், அடுத்த சில நொடிகளில் மரணம் உறுதி. ‘அல்கலாய்ட்’ என்ற விஷம் தவளையின் தோல் முழுவதும் பரவியிருக்கிறது. இந்த விஷம் நரம்புகளின் செயல்களைத் தடுத்துவிடும். தசைகளைச் சுருக்குகிறது. இறுதியில் இதயத்தைச் செயலிழக்க வைத்துவிடும். உள்ளுர் பழங்குடி மக்கள் இதன் நஞ்சை சேகரித்து வேட்டைக்கு பயன்படுத்துகின்றனர். முன்பு வட, தென் அமெரிக்கக் காடுகளில் வாழ்ந்த தவளைகளுக்கு நச்சு இல்லை. காலப் போக்கில் இவை சாப்பிடும் உணவுகளிலிருந்தே நச்சுத்தன்மையைப் பெற்றிருக்க வேண்டும் என்கிறார்கள் ஆராய்ச்சியாளர்கள். [6][7]

தங்க நச்சுத் தவளை ( golden poison frog (Phyllobates terribilis), இதன் வேறு பெயர்கள் golden frog, golden poison arrow frog, golden dart frog ) என்பது கொலொம்பியாவின் பசிபிக் கடற்கரைப் பகுதியல் காணப்படும் நச்சுத்தன்மைவாய்ந்த நச்சு அம்புத் தவளை வகையைச் சேர்ந்த ஒரு ஓரிடவாழி தவளையாகும். இவை ஆண்டு மழையளவு 5 மீ அல்லது அதற்கு மேற்பட்டுள்ளதாகவும், வெப்பநிலை குறைந்தது 26 ° செ என்ற அளவும், கடல் மட்டத்தில் இருந்து 100 மீட்டர் முதல், 200 மீட்டர் வரையும், ஈரப்பதம் 80-90% உள்ள மழைக் காடுகளில் காணப்படுகின்றன. இது ஒரு சமூக விலங்காகும், இவை ஆறு தவளைவரையிலான குழுக்களாக வாழுகின்றன. இந்த தவளைகள் பெரும்பாலும் சிறிய அளவுள்ளதாகவும், பிரகாசமான வண்ணங்கள் கொண்டதாகவும் தீங்கற்றதாகவும் கருதப்படுகிறது, ஆனால் காட்டு தவளைகள் நச்சுத்தன்மை கொண்டதாக உள்ளன. இரண்டு அங்குலமே உள்ள இந்தத் தவளைதான் உலகிலேயே மிக அதிக நச்சு கொண்ட தவளை. ஒரு முறை நச்சை பீய்ச்சி அடித்தால் மூன்றே நிமிடங்களில் 10 மனிதர்களைக் கொன்றுவிடக்கூடியது. பத்து ஆயிரம் சுண்டெலிகளைக் கொன்றுவிடக் கூடியது. இவை பொன் நிறத்தில் மட்டுமின்றி, ஆரஞ்சு, வெளிர் பச்சை நிறங்களிலும் இவை காணப்படுகின்றன. தன் ஆபத்தானவன் என்று மற்ற விலங்குகளை எச்சரிப்பதற்காகவே இவ்வாறு கண்கவர் வண்ணங்கள் கொண்டுள்ளது. அழிந்துவரக்கூடிய அரிய உயிரினங்களின் பட்டியலில் இந்தத் தங்கத் தவளைகளும் உள்ளன. காடுகளை அழித்தல், சட்டத்துக்குப் புறம்பாகத் தங்கச் சுரங்கம் அமைத்தல், கோகோ பயிரிடுதல் போன்ற பல காரணங்களால் தங்கத் தவளைகள் அழிவின் விளிம்புக்குத் தள்ளப்பட்டுள்ளன.

The golden poison frog (Phyllobates terribilis), also known as the golden dart frog or golden poison arrow frog, is a poison dart frog endemic to the rainforests of Colombia. The golden poison frog has become endangered due to habitat destruction within its naturally limited range. Despite its small size, this frog is likely the most poisonous animal on the planet.

The golden poison frog was described as Phyllobates terribilis in 1978 by herpetologists Charles W. Myers and Borys Malkin as well as biochemist John W. Daly;[3] the species name terribilis is a reference to the deadly toxins present in the skin secretions of this species.[2] Myers' research was based on hundreds of specimens collected on an expedition to the Quebrada Guangui and La Brea regions of the Colombian rainforest, and a breeding colony of 18 frogs established at the American Museum of Natural History.[2][4]

The golden poison frog is endemic to humid forests of the Pacific coast of Colombia in the Cauca and Valle del Cauca Departments in the Chocó Rainforest.[3][5] The optimal habitat of this species is the rainforest with high rain rates (5 m or more per year), altitudes from sea level to 200 m elevation, temperatures of at least 26 °C, and relative humidity of 80–90%. It is known only from primary forest. The eggs are laid on the ground; the males transport the tadpoles to permanent pools.[1] Its range is less than 5,000 square km; destruction of this habitat has contributed to P. terribilis becoming an endangered species.[6]

The golden poison frog is the largest species of the poison dart frog family, and can reach a weight of nearly 30 grams with a length of 6 cm as adults.[7] Females are typically larger than males.[4] The adults are brightly colored, while juvenile frogs have mostly black bodies with two golden-yellow stripes along their backs. The black fades as they mature, and at around 18 weeks of age the frog is fully colored.[4] The frog's color pattern is aposematic (a coloration to warn predators of its toxicity).[8] Despite their common name, golden poison frogs occur in four main color varieties or morphs: [9][10][11]

The yellow morph is the reason Phyllobates terribilis has the common name golden poison frog. These frogs can be pale yellow to deep, golden yellow in color. Yellow Phyllobates terribilis specimens are found in Quebrada Guangui, Colombia.[12]

The largest morph of Phyllobates terribilis exists in the La Brea and La Sirpa areas in Colombia; despite the name "mint green" these frogs can be metallic green, pale green, or white.[2][12]

Orange examples of Phyllobates terribilis exist in Colombia, as well. They tend to be a metallic orange or yellow-orange in color, with varying intensity. They have been observed living near yellow specimens in Quebrada Guangui, Colombia, and it is unclear to what extent these represent an individual subpopulation or locality distinct from the yellow morph.[2]

The orange blackfoot morph is a captive bred line established by Tesoros de Colombia, a Colombian company that aims to reduce poaching of wild dart frogs by breeding rare species and flooding the pet trade with low cost animals to decrease the value of wild specimens to poachers.[10] This morph is golden yellow to a deep orange. They have dark markings on their feet, throat, vent, and rump that range from distinct black to nearly absent or speckled grey.[10]

The frog is normally diurnal; golden poison frogs live evenly spaced without forming larger congregations.[9]

This species is an unspecialized ambush hunter; an adult frog can eat food items much larger in relation to its size than most other dendrobatids.[9][13] The main natural sources of food of P. terribilis are the ants in the genera Brachymyrmex and Paratrechina, but many kinds of insects and other small invertebrates can be eaten, specifically termites and beetles, which can easily be found on the rainforest floor. Tadpoles feed on algae, mosquito larvae, and other edible material that may be present in their environment.

Males advertise to receptive females with a trilling call. Golden poison frogs are notable for demonstrating tactile courtship during reproduction, each partner stroking its mate's head, back, flanks, and cloacal areas prior to egg deposition.[14] The eggs are fertilized externally. The golden poison frogs lay their eggs on the ground, hidden beneath leaf litter.[15] Once the tadpoles emerge from their eggs, they stick themselves to the mucus on the backs of their parents. The adult frogs carry their young into the canopy, depositing them in the pools of water that accumulate in the centre of bromeliads and water-filled tree holes.[16][14] The tadpoles feed on algae and mosquito larvae in their nursery.

Golden poison frogs are so toxic that adult frogs likely have few – if any – predators.[4] The snake species Leimadophis epinephelus has shown resistance to several frog toxins including batrachotoxin, and has been observed to eat juvenile frogs without ill effects.[2]

The golden poison frog is the most poisonous animal on the planet; these frogs produce deadly alkaloid batrachotoxins in their skin glands as a defense against predators.[16][17] To become poisoned a predator generally must attempt to consume the frog, although this species is so toxic that even touching an individual frog can be dangerous.[16] This extraordinarily lethal poison is very rare. Batrachotoxin is found only in three poisonous frogs from Colombia (all genus Phyllobates), a few birds from Papua New Guinea, and four Papuan beetles of the genus Choresine in the family Melyridae.[18][19] Batrachotoxin affects the sodium channels of nerve cells. While it is unknown how the frog avoids poisoning itself, other species of poisonous frogs have been demonstrated to express a "toxin sponge" protein in blood plasma, internal organs, and muscle that binds and sequesters the toxin so as to prevent autointoxication.[20]

Batrachotoxin binds to, and irreversibly opens, the sodium channels of nerve cells leaving the muscles in an inactive state of contraction, which can lead to paralysis, heart fibrillation, heart failure, and death.[21] The average dose carried will vary between locations, and consequent local diet, but the average wild golden poison frog is generally estimated to contain about one milligram of poison, enough to kill between 10 and 20 humans, or up to two African bull elephants.[22] [16] Smaller doses have been shown to cause seizures, salivation, muscle contractions, dyspnoea and death in mice: the subcutaneous LD50 is just 0.2 µg / kg, although low doses such as 0.01 µg / kg and 0.02 µg / kg may be lethal.[17] Myers et al. estimate that the lethal dose for humans is between 2.0 and 7.5 µg.[17]

Golden poison frogs appear to rely on the consumption of small insects or other arthropods to synthesize batrachotoxin; frogs kept in captivity fed on commercially available feeder insects will eventually lose their toxicity, and frogs bred in captivity are considered non-toxic.[9][4] It is not clear which prey species supplies the potent alkaloid that gives golden poison frogs their exceptionally high levels of toxicity, or whether the frogs modify another available toxin to produce a more efficient variant, as do some of the frogs from the genus Dendrobates.[22] Scientists have suggested the crucial prey item may be a small beetle from the family Melyridae. At least one species of these beetles produces the same toxin found in golden poison frogs. Their relatives in Colombian rainforests could be the source of the batrachotoxins found in the highly toxic Phyllobates frogs of that region.[19][23]

Golden poison frogs are a very important frog to the local indigenous cultures, such as the Emberá and Cofán people in Colombia's rainforest.[4] The frog is the main source of the poison in the darts used by the natives to hunt their food. The Emberá people carefully expose the frog to the heat of a fire, and the frog exudes small amounts of poisonous fluid. The tips of arrows and darts are soaked in the fluid, and remain deadly for two years or longer.[13]

The golden poison frog is a popular vivarium subject due to its bright color and bold personality in captivity.[10][11][9] Despite its dangerous toxicity in the wild, captive specimens raised without their natural food sources are non-toxic in captivity.[11] Due to their small range in the wild, poaching for the pet trade formerly represented a serious threat to the survival of the species. Due to efforts of frog breeders like Tesoros de Colombia, captive bred frogs are now widely available for the pet trade. As these specimens are legal, non-toxic, healthier, and less expensive when compared to poached animals, the demand for illegally obtained wild caught specimens has decreased.[10] Today, the IUCN estimates that the majority of golden poison frogs sold for the pet trade are legally produced from captive lines, and estimates the threat from collection for the pet trade to be small.[1]

The golden poison frog (Phyllobates terribilis), also known as the golden dart frog or golden poison arrow frog, is a poison dart frog endemic to the rainforests of Colombia. The golden poison frog has become endangered due to habitat destruction within its naturally limited range. Despite its small size, this frog is likely the most poisonous animal on the planet.

La rana dorada venenosa, rana dardo dorada o rana de dardo venenosa (Phyllobates terribilis) es un anfibio anuro de la familia Dendrobatidae endémica de la costa pacífica colombiana. Este anfibio es actualmente considerado el animal más tóxico y venenoso del mundo.[2]

Su hábitat son las selvas húmedas de los departamentos del Chocó, Cauca y Valle del Cauca en la costa pacífica de Colombia El hábitat óptimo de la P. terribilis son los bosques lluviosos con alta tasa de lluvia (5000 mm o más), altitud entre 100 y 200 m, temperaturas de al menos 26 °C y humedad relativa entre 80 % y 90 %.

Normalmente nocturna (activa durante la noche). Es una de las especies más grandes de rana dardo venenosa pues puede alcanzar los 55 mm en la adultez, aunque otras como Dendrobates tinctorius puedan llegar a los 65 o 70 mm. P. terribilis tiene pequeños discos adhesivos en los dedos de sus patas que le ayudan a trepar plantas. Una placa ósea en la mandíbula inferior le da la apariencia de tener dientes, característica no observada en otras especies de Phyllobates. Como todas las ranas dardo, los adultos están brillantemente coloreados, aunque carezcan de las manchas oscuras presentes en otros dendrobátidos, y su patrón de color es aposemático —una pigmentación para advertir a los depredadores su toxicidad—. A veces, es confundida con su prima, Phyllobates truncatus, que tiene la franja verde en las patas traseras; también con Phyllobates bicolor que es muy parecida a P. terribilis variedad naranja, que distinguirlas a simple vista es muy difícil.

P. terribilis puede presentar tres variedades de color:

Esta variedad existe en el área de La Brea, en Colombia, y es la forma más común en cautiverio. El nombre verde menta es en realidad engañoso pues las ranas de esta variedad suelen ser de un verde metálico o un verde pálido, o simplemente blancas.

La variedad amarilla es la razón del nombre común de rana dardo dorada. Estas P. terribilis amarillas son encontradas en la quebrada Guangüí, en Colombia; pueden lucir desde un tono amarillo pálido hasta un profundo dorado. Cierta vez, fue vendida una rana bautizada "Gold Terribilis (Terribilis Oro)", la que confundieron con una P. terribilis amarillo intenso; sin embargo, pruebas genéticas han demostrado que aquellas son una variedad de color uniforme de Phyllobates bicolor o rana dardo de patas oscuras.

Aunque no tan comunes como dos variedades anteriores, existen P. terribilis naranja en Colombia; tienden a ser naranja metálico o amarillo anaranjado con diversas intensidades.

La piel de la rana dardo dorada está impregnada de un alcaloide venenoso, común entre los venenos comunes a las ranas dardo, llamado batracotoxina. Este veneno produce una liberación sostenida de acetilcolina en la placa neuromuscular, lo que trae como consecuencia la contracción muscular tetánica y la muerte por paro respiratorio a causa de una parálisis de los músculos respiratorios, entre otros síntomas de un síndrome colinérgico (miosis, bradicardia, sudoración profusa, disnea por broncoespasmo, cianosis peribucal y distal, etc). Esto puede llevar a fallos cardíacos como la fibrilación. Las ranas pueden mantener altos niveles de batraciotoxina por años incluso después de que se la prive de la fuente de alimento que produce la toxina —las hormigas—. La toxina es activa fuera del cuerpo de estos batracios: pollos y perros han muerto por el contacto con una toalla de papel en la cual una rana P. terribilis había caminado.[3][4] P. terriblis dorada es el animal que carga la toxina más letal del mundo, su piel despide un veneno duradero capaz de eliminar a un humano con velocidad y su cuerpo lo hace inmune a su propio veneno sin embargo al ser inofensivo no representa amenaza a menos de entrar en contacto con la toxina.

La dosis promedio llevada puede variar entre territorios y, por ende, por la dieta local; pero el promedio de veneno en la piel de una P. terribilis salvaje se estima en 1 mg, suficiente para matar alrededor de 10 000 ratones. Esta estimación puede variar, pero la mayoría está de acuerdo en que esta dosis es suficiente para matar entre 10 y 20 seres humanos, o el equivalente a dos elefantes africanos.[5] En promedio serían 15 000 seres humanos por gramo, lo que lo convierte en uno de los venenos más potentes del reino animal.[6]

Este veneno extraordinariamente letal es muy raro. La batracotoxina[7] únicamente se halla en tres ranas tóxicas de Colombia (género Phyllobates) y tres aves tóxicas de Papúa Nueva Guinea: Pitohui dichrous, Pitohui kirhocephalus e Ifrita kowaldi. Otras toxinas afines son la histrionicotoxina y la pumiliotoxina, presentes en especies de ranas del género Dendrobates.

P. terribilis son quizás las únicas criaturas inmunes a su propio veneno. La batracotoxina ataca los canales de sodio de las células, pero esta rana tiene canales de sodio especiales que el veneno no puede dañar; como la mayoría de ranas venenosas, almacenan su toxina en glándulas de la piel; por ello, tienen mal sabor para los depredadores. Su veneno matará a cualquiera que se la coma excepto a la serpiente Liophis epinephelus, resistente al veneno de la rana aunque no completamente inmune.

En cautiverio, debido a que la comida fácilmente adquirible —como moscas de fruta y grillos pequeños— no es rica en el alcaloide que se necesita para fabricar batracotoxina, las ranas dardo doradas no la producen y terminan perdiendo su toxicidad. De hecho, muchos herpetologos han reportado que la mayoría de ranas dardo en cautiverio no consumen hormigas, a pesar de las hormigas constituyen la mayor porción de su dieta en estado salvaje; esto se debe a que sus criadores no disponen de las especies de hormigas que son presa natural de estas ranas. Entonces, todas las ranas venenosas cautivas pierden su toxicidad cuando son privadas de ciertos alimentos y las nacidas en cautiverio son inofensivas, pero una rana venenosa proveniente de estado salvaje puede retener los alcaloides por años. No está claro cuál de las especies de su dieta que suministra el potente alcaloide que le da a la rana dardo dorada su extraordinaria toxicidad, o si las ranas modifican otras toxinas disponibles para producir una variante más efectiva, como lo hacen algunas de sus primas de la familia Dendrobatidae.

Entonces, la alta toxicidad de P. terribilis aparentemente se debe al consumo de un tipo de cucaracha que sería realmente una de las criaturas más venenosas de la Tierra. Los científicos sospechan que este misterioso insecto es un pequeño escarabajo de la familia Melyridae que también produce la toxina de P. terribilis. Este escarabajo 'neoguineano' es cosmopolita: tiene parientes en la selva lluviosa colombiana que podrían ser la fuente de la batracotoxina encontrada en las altamente tóxicas ranas Phyllobates de esa región.[8]

P. terribilis es una rana muy importante para las culturas indígenas locales, tales como los chocó o emberá, en el bosque lluvioso tanto de Colombia como de Panamá. Esta rana es la fuente principal del veneno para dardos que los nativos usan para cazar su alimento.

La gente emberá, cuidadosamente, expone la rana al calor del fuego para que exude pequeñas cantidades de fluido venenoso. La punta de las flechas y dardos se humedecen en el fluido y mantienen su efecto mortal por cerca de dos años.[2][9]

Como las otras ranas dardo venenosas, Phyllobates terribilis es inofensiva cuando es alejada de su fuente natural de alimento; son miembros populares de bioterios del bosque lluvioso y son algo más fáciles de alimentar que otras ranas dardo: grandes especies de moscas de fruta, pequeños grillos, gusanos de seda, pequeños gusanos de harina (Tenebrio molitor), termitas y larvas de mosca soldado negra (Hermetia illucens) pueden emplearse como suplemento junto con calcio y otros minerales. La temperatura debe mantenerse en un punto bajo entre los 20 °C para ellas, pues son sensibles al calor y sufren de una condición llamada síndrome de sudor si son expuestas a altas temperaturas por tiempo prolongado; requieren gran humedad debido a que vienen de uno de los bosques lluviosos más húmedos del mundo. Si bien P. terribilis no son territoriales —como la mayoría de las ranas dardo— y pueden con éxito permanecer en grupos, también requieren un espacio ligeramente mayor debido a su tamaño adulto, similar al utilizado por Dendrobates tinctorius. Puede que ocurran disputas ocasionales, pero las heridas son raras y ninguna muerte se ha reportado como resultado de tales conflictos.

Esta especie se encuentra bajo amenaza de extinción ya que su único hábitat es la selva húmeda, la cual se viene desforestando rápidamente; además, son animales con poca tolerancia a la contaminación.[1]

La rana dorada venenosa, rana dardo dorada o rana de dardo venenosa (Phyllobates terribilis) es un anfibio anuro de la familia Dendrobatidae endémica de la costa pacífica colombiana. Este anfibio es actualmente considerado el animal más tóxico y venenoso del mundo.

Su hábitat son las selvas húmedas de los departamentos del Chocó, Cauca y Valle del Cauca en la costa pacífica de Colombia El hábitat óptimo de la P. terribilis son los bosques lluviosos con alta tasa de lluvia (5000 mm o más), altitud entre 100 y 200 m, temperaturas de al menos 26 °C y humedad relativa entre 80 % y 90 %.

Kuldne lehestikukonn (Phyllobates terribilis) on noolemürgikonn, kelle levila asub Colombia troopikas Vaikse ookeani rannikul.

Kuldse lehestikukonna optimaalse elupaiga määravad vihmametsad, mis on sademerikkad (5000 mm aastas või enam), pinnakõrgus vahemikus 100–200 m, temperatuur vähemalt 26 °C ja suhteline niiskus 80–90%. Vabas looduses on kuldne lehestikukonn sotsiaalne loom, kes elab kuni kuuekesi rühmas, ent tehistingimustes võivad isendid elada ka suuremates rühmades.

Neid konnasid peetakse sageli nende väiksuse ja erksate värvide tõttu kahjutuks, kuid otsene kokkupuude või nende katsuminegi on üldjuhul surmavalt mürgine. Erksad värvid metsikus looduses on tihti biosemiootiliseks signaaliks, et tegu võib olla väga ohtliku elukaga.

Phyllobates terribilis Phyllobates generoko animalia da. Anfibioen barruko Dendrobatidae familian sailkatuta dago, Anura ordenan.

Phyllobates terribilis Phyllobates generoko animalia da. Anfibioen barruko Dendrobatidae familian sailkatuta dago, Anura ordenan.

Kultanuoli (Phyllobates terribilis) on nuolimyrkkysammakoiden heimoon kuuluva sammakkolaji, joka elää vain Kolumbian Tyynenmeren puoleisella rannikolla.[1] Se löydettiin vasta vuonna 1974.[2]

Kultanuoli on suurin nuolimyrkkysammakkolaji, ja painaa 30 grammaa.[2] Se kasvaa noin 4,5 senttiä pitkäksi. Selkäpuoli on keltainen, oranssi tai metallinvihreä, eri alueilla elää erivärisiä sammakoita. Vatsapuoli on samaa väriä kuin selkä mutta vaaleampana, paitsi kämmenet ja reisien sisäsyrjässä olevat läikät ovat mustat. Myös silmät ovat mustat, ja joillain yksilöillä suun reunat. Nuoret yksilöt ovat mustia, keltaraitaisia, ja aikuisvärin sammakko saavuttaa 18 viikon ikäisenä.[3]

Kultanuoli on myös myrkyllisin nuolimyrkkysammakko.[2] Se on erittäin myrkyllinen. Se on yksi kolmesta lajista, jota intiaanit ovat tällä alueella käyttäneet myrkkynuolten valmistamiseen puhallusputkiaan varten.[3] Kultanuolen myrkyllisyys johtuu muun muassa batrakotoksiini-nimisestä (C31H42N2O6, CAS 23509-16-2) sammakkoeläinmyrkystä.

Kultanuoli on erittäin uhanalainen.[1]

Kultanuoli (Phyllobates terribilis) on nuolimyrkkysammakoiden heimoon kuuluva sammakkolaji, joka elää vain Kolumbian Tyynenmeren puoleisella rannikolla. Se löydettiin vasta vuonna 1974.

Kultanuoli on suurin nuolimyrkkysammakkolaji, ja painaa 30 grammaa. Se kasvaa noin 4,5 senttiä pitkäksi. Selkäpuoli on keltainen, oranssi tai metallinvihreä, eri alueilla elää erivärisiä sammakoita. Vatsapuoli on samaa väriä kuin selkä mutta vaaleampana, paitsi kämmenet ja reisien sisäsyrjässä olevat läikät ovat mustat. Myös silmät ovat mustat, ja joillain yksilöillä suun reunat. Nuoret yksilöt ovat mustia, keltaraitaisia, ja aikuisvärin sammakko saavuttaa 18 viikon ikäisenä.

Kultanuoli on myös myrkyllisin nuolimyrkkysammakko. Se on erittäin myrkyllinen. Se on yksi kolmesta lajista, jota intiaanit ovat tällä alueella käyttäneet myrkkynuolten valmistamiseen puhallusputkiaan varten. Kultanuolen myrkyllisyys johtuu muun muassa batrakotoksiini-nimisestä (C31H42N2O6, CAS 23509-16-2) sammakkoeläinmyrkystä.

Kultanuoli on erittäin uhanalainen.

Phyllobate terrible, Kokoï de Colombie

Phyllobates terribilis est une espèce d'amphibiens de la famille des Dendrobatidae, endémique de la côte pacifique de la Colombie. Cet anoure est assez semblable à certaines autres espèces du même genre, en particulier à Phyllobates bicolor. En français, elle est appelée Kokoï de Colombie ou Phyllobate terrible.

Phyllobates terribilis est l'une des plus grandes espèces de Dendrobatidae, atteignant 47 mm de moyenne pour les femelles. Elle se rencontre dans les forêts tropicales humides du département de Cauca, à une altitude comprise entre 100 et 200 m, où la température est d'au moins 25 °C et l'humidité relative élevée. À l'état sauvage, Phyllobates terribilis est un animal sociable, vivant en groupes comprenant jusqu'à six individus ; cependant, cette grenouille peut former des groupes plus importants en captivité.

En raison de sa petite taille et de ses couleurs brillantes, cet amphibien est souvent considéré comme inoffensif alors que les spécimens sauvages sont mortellement toxiques, car ils stockent dans les glandes de leur peau de la batrachotoxine. Ainsi, un contact direct avec une grenouille sauvage peut suffire, pour un humain, à causer une sensation de brûlure qui dure plusieurs heures. Son aire de répartition ne cesse d'être en recul, notamment en raison de l'impact des activités de l'Homme sur son habitat naturel et l'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature la considère comme « espèce en danger ».

Phyllobates terribilis est considérée comme l'une des plus grandes espèces de la famille des Dendrobatidae[A 1]. Il y a peu de dimorphisme sexuel entre les mâles et les femelles, sauf une légère différence de taille, les femelles étant un peu plus grandes en moyenne. Pour les spécimens adultes, les mâles, dont la longueur moyenne du museau au cloaque est de 45 mm, sont en effet généralement un peu plus petits que les femelles, qui mesurent en moyenne 47 mm[A 2].

Comme tous les Dendrobatidae, le corps et les membres du Phyllobates terribilis adulte sont de couleur vive mais n'ont pas les taches sombres présentes sur de nombreuses autres espèces de cette famille. La coloration de cette grenouille est dite aposématique car il s'agit d'une pigmentation de couleur vive alertant ses prédateurs potentiels de sa haute toxicité. Ainsi, la coloration uniforme de leur peau peut être jaune d'or, orange doré ou vert pâle métallique. Le canthus rostralis est arrondi tandis que la partie loréale est verticale et légèrement concave[A 3]. L'iris des yeux, dont la pupille est horizontale, les narines, le bout des doigts, le bord inférieur des membranes tympaniques et les bordures de la bouche sont noirs. Il en est de même pour les plis de la peau au niveau des aisselles et de l'aine. Phyllobates terribilis a quatre doigts sur les membres antérieurs, le troisième étant le plus grand lorsqu'ils sont mesurés à plat ; suivent ensuite le quatrième, puis le premier et le deuxième qui sont de taille équivalente. Cinq doigts terminent les membres postérieurs, le quatrième étant le plus long. Suivent, du plus grand au plus petit, le troisième, le cinquième, le deuxième puis le premier doigt[A 3]. De petits disques-ventouses sont présents au bout des doigts qui lui permettent de grimper aux plantes. Les dents sont présentes sur l'arc maxillaire de la bouche de Phyllobates terribilis. Les jeunes grenouilles de cette espèce sont noires avec des rayures dorées sur la face dorsale[A 4],[1].

Les diverses colorations possibles de la peau de Phyllobates terribilis semblent dépendre des variations micro-géographiques. Ainsi, dans la localité de Quebrada Guangui, la plupart des spécimens trouvés sont jaune d'or ou orange doré, les autres étant de couleur vert pâle ou orange intense. Dans une autre localité située à 15 km appelée La Brea, les grenouilles sont plutôt vert pâle métallique[A 3]. Leur ventre et la partie intérieure de leurs cuisses peuvent parfois tendre vers le bleu-vert[1]. Cependant, quelle que soit la localité où se situent les Phyllobates terribilis, elles ont la même morphologie, aucune différence significative au niveau de la toxicité de la peau n'ayant, par ailleurs, été détectée[A 3]. Les mâles adultes possèdent un sac vocal peu profond dont la présence est signalée par de petits sillons jugulaires épidermiques dans une zone grisâtre à la base de la gorge. Ils ont également des fentes vocales appairées sur le plancher buccal[A 2],[1].

Phyllobates terribilis ressemble beaucoup à Phyllobates bicolor, espèce également endémique de Colombie mais qui se rencontre seulement de 400 à 1 500 m d'altitude dans les départements de Chocó et de Valle del Cauca. Cette dernière se distingue de Phyllobates terribilis par sa plus petite taille ainsi que par la coloration différente de son ventre et de ses extrémités par rapport à sa face dorsale[A 1].

Chez les batraciens, les batrachotoxines ont été seulement détectées sur les grenouilles du genre Phyllobates, ces substances étant parmi les plus toxiques au monde[2]. Phyllobates terribilis est considérée comme la grenouille la plus toxique au monde[1],[3]. Sécrétés par la peau[A 5], ces alcaloïdes stéroïdiens sont stockés dans les glandes de la peau de la grenouille, plus nombreuses au niveau du dos[1]. La batrachotoxine agit en se fixant sur des canaux sodiques qui restent ouverts[4] et empêche les nerfs de transmettre les impulsions électriques, laissant les muscles dans un état de relâchement et pouvant ainsi entraîner une insuffisance cardiaque ou une fibrillation[5],[6]. Par ailleurs, des sécrétions de la peau de cet amphibien ayant été transférées accidentellement des mains au visage causent une sensation de brûlure prononcée qui dure plusieurs heures[A 6]. Chez les grenouilles de la famille des Dendrobatidae, ce poison est un mécanisme d'autodéfense et ne sert donc pas à tuer leurs proies[7]. La noranabasamine, alcaloïde de pyridine, ne se rencontre que chez Phyllobates aurotaenia, Phyllobates bicolor et Phyllobates terribilis[8].

La peau de Phyllobates terribilis, qui affiche des couleurs vives dites aposématiques, recèle entre 700 et 1 900 µg de toxine[1], ce qui est suffisant pour tuer plus de 10 000 souris ou environ 10 à 20 humains. Ainsi, moins de 200 µg injectés dans le système sanguin d'un être humain peut s'avérer fatal[9]. Les sécrétions de la peau de cette grenouille sont également irritantes pour la peau poreuse, et toxiques si elles sont ingérées[A 7].

Contrairement à certaines grenouilles australiennes du genre Pseudophryne de la famille des Myobatrachidae qui peuvent biosynthétiser leur propre alcaloïde (la pseudophrynamine)[12], la forte toxicité de Phyllobates terribilis semble être due à la consommation d'arthropodes, en particulier d'insectes. Certains scientifiques supposent que l'insecte responsable du processus de synthèse qui rend la grenouille toxique est un petit coléoptère du genre Choresine de la famille cosmopolite des Melyridae ; ces insectes recèlent en effet cette toxine à faible dose[13],[14]. Ce poison extrêmement létal est très rare dans le règne animal. La batrachotoxine, qui est stockée dans les glandes de la peau des grenouilles du genre Phyllobates à des degrés divers (Phyllobates lugubris et Phyllobates vittatus en produisant bien moins que les autres)[A 6], a également été retrouvée dans les plumes et la peau de cinq oiseaux toxiques de la Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée (le Pitohui bicolore, le Pitohui variable, le Pitohui huppé, le Pitohui noir et l'Ifrita de Kowald[15]). Chez les espèces de grenouilles du genre Dendrobates, qui dépendent de la sous-famille des Dendrobatinae comme Phyllobates terribilis, on retrouve également d'autres toxines telles que l'histrionicotoxine et la pumiliotoxine[16].

Les têtards de Phyllobates terribilis ne contiennent pas de batrachotoxine ; en revanche, il a été trouvé chez de jeunes grenouilles de 27 mm de longueur museau-cloaque jusqu'à 200 µg de toxine, ce qui signifie que la batrachotoxine est synthétisée ou stockée après leur métamorphose. Les spécimens sauvages mis en captivité depuis un an perdent 50 % de leur toxicité et 60 % sur une période de trois ans. En revanche, les grenouilles nées et élevées en captivité ne contiennent pas de toxines dans leur peau mais peuvent cependant en accumuler si elles font partie de leur alimentation[1].

Les scientifiques savaient depuis les années 1980 que les muscles et les nerfs de Phyllobates terribilis étaient insensibles à la batrachotoxine[4]. Néanmoins, ce n'est qu'en 2017 qu'une équipe de chercheurs américains de l'université d'État de New York découvre que ce serait grâce à une seule mutation génétique que la grenouille peut produire cette toxine sans s'empoisonner elle-même[4],[17]. Ainsi, après avoir testé cinq substitutions d'acides aminés naturels trouvées dans le muscle de Phyllobates terribilis, les chercheurs ont observé que la batrachotoxine n'a pas d'effet, ne se fixant plus sur le canal, lorsque le 1 584e acide aminé du canal sodique est la thréonine à la place de l'asparagine[4],[17]. Cette variation précise, naturellement présente chez Phyllobates terribilis, serait due à la mutation d'un seul nucléotide[4],[17].

Phyllobates terribilis est une grenouille diurne qui vit exclusivement sur la terre ferme, bien que certaines aient été retrouvées perchées à quelques centimètres du sol sur des racines d'arbres[A 8]. Lorsqu'elles sont dérangées, elles sautent en général un peu plus loin, plutôt que d'essayer de se cacher[1]. Leur chant est décrit comme un « long trille mélodieux », l'aspect « trillé » de leur chant étant dû à une succession rapide de notes distinctes émises à un rythme de 13 notes par seconde, avec une fréquence dominante de 1,8 kHz inférieure à celle de Phyllobates aurotaenia, Phyllobates bicolor, Phyllobates lugubris et Phyllobates vittatus[A 9],[1].

Lors de la parade nuptiale, le mâle attire la femelle avec des trilles fort bruyants. Lorsqu'il parvient à attirer la femelle, il la conduit vers un site de ponte approprié qui doit être couvert, propre, lisse et humide tel qu'une feuille ou une pierre. Le potentiel de reproduction, avec 20 œufs par ponte, est plus faible pour la femelle Phyllobates terribilis que chez d'autres anoures, bien qu'elle puisse se reproduire tous les mois[A 10]. Après que la femelle a pondu les œufs, ceux-ci sont fertilisés par le mâle[18]. Si on exclut la substance gélatineuse qui les entoure, ils mesurent entre 2,4 et 2,6 mm de diamètre[A 11]. Ils éclosent vers le treizième jour environ et le mâle récupère alors les larves sur son dos. Les têtards sont généralement portés une journée par le mâle, puis sont déposés dans un petit point d'eau afin de pouvoir nager et se développer[18].

Les têtards, qui sortent de l'eau 55 jours environ après l'éclosion, changent d'apparence tout au long de leur développement[A 11]. À la naissance, leur corps mesure en moyenne 4,1 mm et leur longueur totale (queue comprise) est de 11,1 mm. Par la suite, ils atteignent une longueur totale de 35,4 mm pour une taille moyenne de corps de 12,6 mm[1]. Leur corps, d'abord gris-noirâtre avec des bandes de couleur bronze pâle sur le dos, devient peu à peu noir avec des bandes dorsales de plus en plus jaune brillant, ses membres antérieurs grandissant dans le même temps. Puis, la couleur noire de la peau disparaît progressivement, laissant place à une couleur uniforme : jaune, orange, vert métallique voire blanc[A 12]. Le ventre met encore plusieurs semaines avant d'atteindre la même couleur brillante que le reste du corps[1]. Lorsque les jeunes Phyllobates terribilis sont encore noires avec des bandes dorsales jaunes, elles ressemblent quelque peu à Phyllobates aurotaenia adulte mais s'en distinguent par l'absence de couleur bleue ou verte sur le ventre[A 13].

Les jeunes grenouilles se nourrissent de petits insectes tels que les drosophiles. Les mâles arrivent à leur maturité sexuelle quand ils atteignent les 37 mm alors que pour les femelles, cette taille est de 40 à 41 mm[A 11].

À l'état sauvage, Phyllobates terribilis se nourrit principalement de fourmis du genre Brachymyrmex et Paratrechina ainsi que de nombreux autres petits invertébrés et insectes, tels que les termites et les scarabées, qui se trouvent à même le sol de la forêt. Considérée comme la plus vorace des Dendrobatidae[19], cette grenouille capture ses proies grâce à sa langue gluante[20]. En captivité, la grenouille est nourrie avec des mouches des fruits, des cochenilles, des grillons Gryllidae, diverses larves d'insectes et autres petits invertébrés vivants. Un spécimen adulte peut manger des aliments beaucoup plus grands par rapport à sa taille que la plupart des autres espèces de la famille des Dendrobatidae.

Phyllobates terribilis n'a qu'un seul prédateur naturel actuellement connu, à savoir le serpent arboricole Erythrolamprus epinephelus qui attaque principalement les jeunes grenouilles, sa mâchoire étant trop petite pour avaler celles de taille adulte[A 10]. En effet, ce serpent tropical est résistant aux toxines produites par les grenouilles des genres Dendrobates, Phyllobates et Atelopus[21].

L'Humain est la cause de la réduction des effectifs de cet amphibien. Ce dernier est utilisé dans le cadre de la chasse par les Amérindiens Emberá et Noanamá pour empoisonner leurs flèches de sarbacane[A 14], mais la principale menace est la destruction de son habitat par l'Homme[1].

Cette espèce est endémique de Colombie. Elle se rencontre sur la côte du Pacifique de la Colombie dans le département de Cauca, à une altitude comprise entre 100 et 200 m, au niveau du bassin supérieur du río Saija. Elle vit dans les forêts tropicales humides ayant de forts taux de pluie (5 m ou plus), à une température d'au moins 25 °C et une humidité relative variant de 80 à 90 %. La végétation au sol est principalement composée de jeunes arbres de petite taille, de petits palmiers, de plantes herbacées et de fougères[22]. Généralement, Phyllobates terribilis vit sur la terre ferme[A 8] dans la forêt, aussi bien sur des crêtes que sur des pentes humides, près des petits cours d'eau plutôt que les abords de plus grands cours d'eau qui ont été défrichés pour l'agriculture[A 15].

Des spécimens de cet amphibien ont également été découverts dans le département d'Antioquia[23].

Phyllobates terribilis est une espèce d'amphibiens de la famille des Dendrobatidae[24]. Alors qu'il travaille au sein du NIH depuis 1958, John William Daly accepte en 1953 d'orienter ses recherches sur les alcaloïdes bioactifs lorsque son chef de laboratoire, Bernhard Witkop, lui propose d'aller travailler à l'ouest de la Colombie sur les toxines des grenouilles venimeuses. Ainsi, les spécimens collectés près du Río San Juan s'avèrent contenir plusieurs batrachotoxines et font l'objet d'un article dans la revue Medical World News. Charles William Myers, alors étudiant diplômé en herpétologie, s'intéresse aux « implications taxonomiques et évolutives des toxines, qui ont également de nouvelles propriétés pharmacologiques ». Il propose à Daly qu'ils collaborent à une étude des grenouilles toxiques du Panama afin de déterminer si leur coloration brillante et leur toxicité sont liées. Finalement, en 1973, avec l'aide de Borys Malkin, ils collectent plusieurs Phyllobates terribilis près du Río Saija, en Colombie. L'étude et la description de ces grenouilles, intitulée « A dangerously toxic new frog (Phyllobates) used by Emberá Indians of Western Colombia, with discussion of blowgun fabrication and dart poisoning » (« Une nouvelle grenouille dangereusement toxique (Phyllobates) utilisée par les Indiens Emberá de l'ouest de la Colombie, avec discussion sur la fabrication de sarbacanes et l'empoisonnement de fléchettes »), paraît pour la première fois en 1978. Quelques années plus tard, John William Daly, qui aurait aimé connaître l'origine des batrachotoxines de Phyllobates terribilis en récupérant de nouveaux spécimens, doit renoncer à son projet car, selon lui, « dorénavant, il est trop difficile d'obtenir un permis de collecte en Colombie »[25].

L'origine du nom du genre Phyllobates dérive des termes grecs phyllo qui signifie « feuille » et bates qui veut dire « grimpeur », faisant référence au comportement de certains amphibiens de la famille des Dendrobatidae qui montent aux arbres[26]. L'épithète spécifique terribilis, choisie par Daly et Myers, est un adjectif latin signifiant « terrible » ou « effrayant ». Il fait référence à la toxicité extraordinaire des sécrétions de la peau de ces grenouilles et se rapporte également à la crainte évoquée par les flèches de sarbacane empoisonnées utilisées par des peuples indigènes[A 16]. « Kokoï », qui est le nom vernaculaire de Phyllobates terribilis, est notamment utilisé par les Noanamá et les Emberá. Ces deux groupes ethniques amérindiens donnent également ce nom à Phyllobates aurotaenia[A 17].

L'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature (UICN) considère qu'il s'agit d'une « espèce en danger » (EN), sa zone d’occurrence étant estimée à moins de 5 000 km2, les individus de l'espèce étant par ailleurs localisés dans seulement cinq zones. Enfin, une baisse continue de l'étendue et de la qualité de l'environnement de Phyllobates terribilis dans le département de Cauca a été constatée par cette ONG[27]. Le déclin de la population de Phyllobates terribilis peut être expliqué par plusieurs facteurs tels que le déboisement et les activités liées à l'exploitation du bois, le développement de l'agriculture intensive ainsi que l'emploi de divers engrais, pesticides et produits polluants[1]. Cette grenouille doit également faire face au trafic illégal, étant souvent exportée à l'étranger pour des compagnies pharmaceutiques situées dans des pays industrialisés tels que le Canada ou l'Allemagne qui souhaitent étudier les puissants alcaloïdes stéroïdiens qu'elle contient[3].

Comme les autres Dendrobatidae, Phyllobates terribilis est touchée par l'explosion mondiale de la chytridiomycose cutanée qui a amené certaines espèces au bord de l'extinction[7], certains spécimens en captivité étant également atteints par cette maladie.

Phyllobates terribilis figure dans l'annexe II de la CITES depuis le 22 octobre 1987[28]. Fin août 2013, le quota d'exportation s'élève à 240 spécimens vivants et élevés en captivité pour la Colombie[28]. Par ailleurs, dans ce pays, le décret no 39 du 9 juillet 1985 de l'INDERENA (« Instituto nacional de recursos naturales » ou « Institut national des ressources naturelles ») interdit le prélèvement de Phyllobates dans la nature, que ce soit pour les élever ou pour tout autre but[27].

Phyllobates terribilis a besoin d'un environnement chaud et humide, avec beaucoup de nourriture et agrémenté de cachettes. La température doit rester supérieure à 20 °C, mais avec un maximum d'environ 25 °C[18], et une humidité de 80 % ou plus[29]. Cette grenouille en captivité s'adapte vite à son environnement, associant très rapidement l'ouverture de son terrarium au fait de recevoir sa nourriture composée notamment de grillons saupoudrés de vitamines et de calcium[A 8]. À ce régime alimentaire, peuvent notamment s'ajouter des mouches domestiques, des cloportes ou encore des larves d'insectes[29]. Lorsqu'ils se nourrissent, certains spécimens mâles ont un comportement agressif, appuyant la surface supérieure de leurs mains contre le menton de leur adversaire[A 8]. En captivité, cette espèce de batraciens, qui a une espérance de vie allant jusqu'à 10 ans[30], peut vivre dans des groupes composés de dix à quinze individus alors qu'elle vit en petits groupes de six maximum dans la nature[7].

L'élevage de Phyllobates terribilis est réglementé. Par exemple, selon la législation française, l'arrêté du 21 novembre 1997 définit le genre Phyllobates en tant qu'espèce considérée comme dangereuse. À ce titre, son élevage sur le territoire français est soumis à l'obtention d'un certificat de capacité et d'une autorisation d'ouverture d'établissement[31].

Phyllobates terribilis est la plus toxique de toutes les grenouilles. Ainsi, avec Phyllobates aurotaenia et Phyllobates bicolor, elle est l'une de trois espèces connues pour être utilisées dans le cadre de la chasse par des peuples amérindiens de Colombie. C'est notamment le cas de deux groupes constitutifs du peuple Chocó : les Noanamá et les Emberá[A 14] qui, pour empoisonner leurs flèches de sarbacane, les frottent au préalable sur la peau de Phyllobates terribilis lorsqu'elle est vivante[A 17]. Avec ces fléchettes, ils peuvent ainsi tuer des animaux comme des tapirs[23]. La méthode est différente pour les deux autres espèces de grenouilles qui sont moins toxiques. En effet, après les avoir empalé sur une tige de bambou[A 18], les Amérindiens chocoes les exposent vivantes au-dessus d'un feu afin que leur corps exsude une sorte d'huile jaune[32]. Ils imprègnent ensuite la pointe de leurs flèches avec le liquide[33] qu'ils ont recueilli en raclant la peau du batracien[32]. Bien que le poison utilisé sur les flèches soit très puissant, les Amérindiens peuvent manger sans risque d'intoxication les animaux qu'ils ont tués durant la chasse. En effet, bien que toutes les toxines ne soient pas thermolabiles, la cuisson de la viande va globalement les détruire[34].

Outre son utilisation dans le cadre de la chasse, les composants du poison de Phyllobates terribilis sont étudiés par l'industrie pharmaceutique dans le but de créer des médicaments tels que des relaxants musculaires, des analgésiques aussi puissants que la morphine et des stimulants cardiaques[35].

Phyllobate terrible, Kokoï de Colombie

Phyllobates terribilis est une espèce d'amphibiens de la famille des Dendrobatidae, endémique de la côte pacifique de la Colombie. Cet anoure est assez semblable à certaines autres espèces du même genre, en particulier à Phyllobates bicolor. En français, elle est appelée Kokoï de Colombie ou Phyllobate terrible.

Phyllobates terribilis est l'une des plus grandes espèces de Dendrobatidae, atteignant 47 mm de moyenne pour les femelles. Elle se rencontre dans les forêts tropicales humides du département de Cauca, à une altitude comprise entre 100 et 200 m, où la température est d'au moins 25 °C et l'humidité relative élevée. À l'état sauvage, Phyllobates terribilis est un animal sociable, vivant en groupes comprenant jusqu'à six individus ; cependant, cette grenouille peut former des groupes plus importants en captivité.

En raison de sa petite taille et de ses couleurs brillantes, cet amphibien est souvent considéré comme inoffensif alors que les spécimens sauvages sont mortellement toxiques, car ils stockent dans les glandes de leur peau de la batrachotoxine. Ainsi, un contact direct avec une grenouille sauvage peut suffire, pour un humain, à causer une sensation de brûlure qui dure plusieurs heures. Son aire de répartition ne cesse d'être en recul, notamment en raison de l'impact des activités de l'Homme sur son habitat naturel et l'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature la considère comme « espèce en danger ».

A Phyllobates terribilis,[3] é unha especie de ra velenosa endémica da costa pacífica de Colombia. Este anfibio está considerado o vertebrado máis tóxico do mundo.[4] O seu hábitat son as selvas húmidas dos departamentos de Chocó, Cauca e Valle del Cauca na costa pacífica de Colombia e Panamá na rexión selvática de Darién.[5] O hábitat óptimo da P. terribilis son os bosques húmidos con alta taxa de choiva (5000 mm ou máis), altitude entre 100 e 200 m, temperaturas de polo menos 26 °C e humidade relativa entre 80 % e 90 %.

A Phyllobates terribilis, é unha especie de ra velenosa endémica da costa pacífica de Colombia. Este anfibio está considerado o vertebrado máis tóxico do mundo. O seu hábitat son as selvas húmidas dos departamentos de Chocó, Cauca e Valle del Cauca na costa pacífica de Colombia e Panamá na rexión selvática de Darién. O hábitat óptimo da P. terribilis son os bosques húmidos con alta taxa de choiva (5000 mm ou máis), altitude entre 100 e 200 m, temperaturas de polo menos 26 °C e humidade relativa entre 80 % e 90 %.

La rana dorata o rana freccia (Phyllobates terribilis Myers, Daly, e Malkin, 1978) è un piccolo anfibio anuro, vivacemente colorato, appartenente alla famiglia Dendrobatidae, diffuso nelle foreste pluviali delle Ande occidentali colombiane.[2]

Il suo aspetto viene considerato un classico esempio di aposematismo, essendo l'anfibio estremamente tossico.

La rana dorata è un anfibio di piccolissime dimensioni, sebbene P. terribilis sia considerato una delle più grandi specie della famiglia dei Dendrobatidae. C'è poco dimorfismo sessuale, ad eccezione di una leggera differenza di dimensioni: in media le femmine sono leggermente più grandi. Infatti i maschi adulti, con una lunghezza media di 45 mm, sono generalmente più piccoli delle femmine, la cui dimensione media è 47 mm. I maschi raggiungono la maturità sessuale quando raggiungono i 37 mm e le femmine a 40–41 mm. Come tutti Dendrobatidae il corpo del Phyllobates terribilis adulto ha colori vivaci, ma non ha le macchie scure presenti su molte altre specie di questa famiglia.

La pelle è di colore generalmente giallo vivo, una colorazione aposematica che serve come avvertimento agli eventuali predatori e i vari colori possibili della pelle sembrano dipendere da micro-variazioni geografiche. Talvolta la cute è leggermente maculata di nero nella zona cefalica. Gli occhi sono neri e piuttosto grandi. Anche le palpebre sono nere, in modo tale da far apparire l'animale con gli occhi sempre aperti. Le zampe posteriori sono più lunghe di quelle anteriori, in modo da consentire di saltare agilmente. Il colore uniforme della pelle può essere giallo oro, arancio dorato pallido o metallo verde. La cresta rostrale è arrotondata mentre la parte loreale è verticale e leggermente concava. L'iride dell'occhio, la cui pupilla è orizzontale, il naso, le dita, il bordo inferiore della membrana timpanica ed i bordi della bocca sono neri. Ugualmente per le pieghe della pelle sotto le ascelle e inguine. P. terribilis ha quattro dita sulle zampe anteriori, il terzo è il più grande, quando misurato in piano, e ha cinque dita l'estremità posteriore, il quarto è il più lungo. Ventose di piccola taglia sono situate all'estremità digitali. I denti sono presenti sul mascellare orale. Le rane giovani di questa specie sono di colore nero con strisce oro sul lato dorsale.

Durante il corteggiamento il maschio attira la femmina con richiami forti e rumorosi e la porta ad un sito adatto alla riproduzione, zona pulita, liscia e umida come una foglia o una pietra. Il potenziale riproduttivo, con 20 uova per accoppiamento, è più basso rispetto ad altri anuri, anche se questa rana può riprodursi ogni mese. Dopo che la femmina ha deposto le uova, esse vengono fecondate dal maschio. Se si esclude la sostanza gelatinosa che le circonda, misurano tra 2,4 e 2,6 millimetri di diametro. Si schiudono circa al tredicesimo giorno e le larve vengono poste dal maschio sulla schiena. I girini sono di solito portati dal maschio per un giorno e poi sono collocati in un piccolo specchio d'acqua per nuotare e svilupparsi. I girini, che emergono dalle acque circa 55 giorni dopo la schiusa, modificano il loro aspetto durante tutta la metamorfosi. Alla nascita il corpo è in media 4,1 mm e lunghezza totale, compresa la coda, è 11,1 millimetri. Successivamente raggiungono una lunghezza totale di 35,4 mm.

La pelle della rana è densamente ricoperta di un velenoso alcaloide, uno di una serie di veleni comuni nelle rane freccia, le batracotossine, molecole che impediscono ai nervi di trasmettere impulsi, lasciando i muscoli in uno stato inattivo di contrazione ovvero tetanizzati, per analogia con gli effetti della tetanospasmina la tossina peptidica prodotta da C.tetani agente del tetano. Questo può portare a insufficienza respiratoria, insufficienza cardiaca o fibrillazione. Alcuni nativi utilizzano questo veleno per cacciare con frecce ricoperte di veleno. L'alcaloide può essere conservato dalle rane per anni dopo che esse siano state private di un alimento base per la sintesi del veleno e le tossine di questo tipo non si deteriorano facilmente, anche quando vengono trasferite su un'altra superficie.